Afterword: Citizen of the Macrocosm

Robert Zend admired Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy for his unwillingness “to accept any label, either for himself or for others”:

He didn’t identify with any group; he belonged nowhere, but this non-belonging meant for him an extremely strong belonging to Man, to Mankind, to Humanity.1

Zend similarly disregarded boundaries in seeking out like-minded writers and artists around the world, in shaping themes exploring the connectedness of all humanity and a cosmic sense of place, and in creating art using the most humble and mundane objects.

National culture is a fuzzy proposition, and this is true for the countries where Zend found kindred artists and writers. At a certain point, the idea of nation becomes merely a convenient rubric to demonstrate his cosmopolitanism. For example, within Canadian culture are the cultures of many nations. In turn, the cultures of those nations cannot be thought of as pure but are often congeries of contributions from many peoples across history. As Zend resisted the notion of labels and boundaries, my use of them here might seem to contradict his convictions.

But nations, perhaps especially one such as Hungary, whose language and culture evoke in many Hungarians fierce sentiments of belonging, are of course not totally artificial cultural constructs. And although Canada’s historical quest for a cohesive national culture has been eroded over the decades by the crosscurrent trend toward a national policy of multiculturalism, Canadian cultural protectionism has cast an enduring shadow on any debate on national identity.

Zend had Hungarian cultural roots, and part of his cosmopolitan Budapest heritage was also the thirst to look beyond borders to find literary and artistic kin worldwide. This desire was integral to the freedom that he so valued. In Canada, he had close ties to immigrant as well as Canadian-born artists and writers. Thus his Canadian heritage and legacy are based not so much on national identity as on multicultural affinities.

In the afterword to Oāb, he lists his “spiritual fathers and mothers” as well as “chosen brothers and sisters.” They include poets, artists, sculptors, short story writers, novelists, philosophers, literary theorists, actors, and filmmakers from Argentina, Canada, the United States, France, Austria, Germany, Ancient Greece and Rome, Romania, Flanders, Holland, Ireland, Italy, Russia, Hungary, Great Britain, and Belgium. In short, his tally of creative family is a model of interdisciplinary and cosmopolitan openness.

Zend was a Canadian original: born in Hungary and adopted by Canada, he wrote about both places. He was also a citizen of a broader community of writers and artists and wrote about realms of cosmic dimension. His cosmopolitan outlook is a part of Canadian cultural history. It is a remarkable achievement and an homage to what he most admired in other writers, artists, and cultures without regard to borders.

Thank you for reading my series on the life and work of Robert Zend — I hope you enjoyed it. It has been a great pleasure to work on this project.

A Special Announcement —

The Robert Zend Website

One important matter remains: in a few days, I’ll announce the completion of a significant project recently undertaken by Zend’s daughter Natalie Zend: The Robert Zend Website. This valuable resource provides information on acquiring his books and art and offers information to anyone interested in learning more about his remarkable life and work. Stay tuned . . .

Acknowledgements and Bibliography

Below is a list of heartfelt acknowledgements to the many people who have kindly assisted my research. Particular gratitude goes to Janine Zend, Natalie Zend, and Ibi Gabori, who so generously contributed to this project. Please do not hesitate to let me know if I have overlooked any person or institution.

And for anyone interested in the sources I used during my research, I include a Bibliography at the end of this post.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the kind assistance and generosity of the following:

The family of Robert Zend: Janine Zend, Natalie Zend, and Ibi Gabori

Rachel Beattie and Brock Silverside, curators of the Zend fonds at Media Commons, University of Toronto Library

Edric Mesmer, librarian at the University at Buffalo’s Poetry Collection and curator of The Center for Marginalia, and the other wonderful librarians of The Poetry Collection for their research assistance

Brent Cehan and other librarians of the Language and Literature division of the Toronto Reference Library

The librarians in the Special Arts Room Stacks at the Toronto Reference Library

The librarians at Reference and Research Services and at the Petro Jacyk Central and East European Resource Centre, Robarts Library, University of Toronto Libraries

Susanne Marshall (former Literary Editor for The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Irving Brown

Robert Sward

bill bissett

Jiří Novák

Bibliography

“Administrative history / biographical sketch.” Robert Zend fonds. Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries, Toronto, Canada. http://mediacommons.library.utoronto.ca/sites/mediacommons.library.utoronto.ca/files/finding-aids/zend.pdf

Bangarth, Stephanie, and Andrew S. Thompson. “Transnational Christian Charity: the Canadian Council of Churches, the World Council of Churches, and the Hungarian Refugee Crisis, 1956–1957.” American Review of Canadian Studies 38, no. 3 (2008): 295–316. General OneFile. Web.

The Book of Canadian Poetry. Edited by A. J. M. Smith. Toronto: Gage, 1943.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Comments on back cover of Daymares: Selected Fiction on Dreams and Time by Robert Zend. Vancouver: CACANADADADA Press, 1991.

———. Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings. Edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. New York: New Directions, 1964.

Botar, Oliver, to Janine Zend. Email. 9 April 2001.

Buzinkay, Géza. “The Budapest Joke and Comic Weeklies as Mirrors of Cultural Assimilation.” In Budapest and New York: Studies in Metropolitan Transformation, 1870–1930, edited by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske, 224–247. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1994.

Catalogue. Országos Széchényi Könyvtár (National Széchényi Library) in Budapest, Hungary.

Cavell, Richard. McLuhan in Space: A Cultural Geography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003.

Clarity, James F., and Eric Pace. “Marcel Marceau, Renowned Mime, Dies at 84.” New York Times. 24 September 2007.

Colombo, John Robert. Ottawa Journal. 11 May 1974. 40.

Day, Lawrence. “Re: Handbook 386(b) – Ken Field.” Chess Talk. 27 August 2008. http://www.chesstalk.info/forum/printthread.php?s=bea6d4e5851d02610f6670258010f473&t=375

———. IMlday. 23 September 2004. http://www.chessgames.com.

Donaghy, Greg. “An Unselfish Interest? Canada and the Hungarian Revolution, 1954-1957.” In The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: Hungarian and Canadian Perspectives, edited by Christopher Adam, Tibor Egervari, Leslie Laczko, and Judy Young, 256—74. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2010.

Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. “Hungary: The Great Depression.” Library of Congress Country Studies. 1989. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cshome.html.

Ferrazzi, A. Portrait of Giacomo Leopardi. C. 1820. Oil on canvas. Casa Leopardi, Recanati, Italy.

“Fiftieth Anniversary of the Hungarian uprising and refugee crisis.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 23 October 2006. http://www.unhcr.org/453c7adb2.html.

Fifield, William. “The Mime Speaks: Marcel Marceau.” The Kenyon Review 30, no.2 (1968): 155-65.

Fleeing the Hungarian Revolution, Settling in Canada: Photos and documents of Robert, Ibi and Aniko Zend’s voyage November 1956 – April 1957. 1956 Memorial Oral History Project: Materials accompanying Eve (Ibi) Gabori’s interview, 31 March 2007. Prepared by Natalie Zend, 24 June 2007.

Fosler-Lussier, Danielle. Music Divided: Bartók’s Legacy in Cold War Culture. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007.

Frye, Northrop. Afterword to Daymares: Selected Fictions on Dreams and Time, by Robert Zend. Vancouver: Cacanadada Press, 1991.

Gabori, George. When Evils Were Most Free. Deneau, 1981.

Gabori, Ibi. Interview 01544-2. Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation Institute. Accessed online at the University of Toronto Library.

Gould, Glenn. “If I were a gallery curator . . .” Dust jacket of From Zero to One by Robert Zend. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Mission, BC: The Sono Nis Press, 1973.

Hahn, Lionel / McClatchy Newspapers. Photograph of Marcel Marceau performing in Westwood, California, in 2002. Available from: The Seattle Times. http://seattletimes.com/html/nationworld/2003899052_marceau24.html.

Hamlet. Directed by Lawrence Olivier. London: Two Cities Films, 1948.

Hidas, Peter. “Arrival and Reception: Hungarian Refugees, 1956—1957.” In The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: Hungarian and Canadian Perspectives, edited by Christopher Adam, Tibor Egervari, Leslie Laczko, and Judy Young, 223—55. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2010.

History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Volume 1. Edited by Marcel Cornis-Pope and John Neubauer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2004.

Hungarian American Federation. “The 1956 Hungarian Revolution in Photos.“ The 1956 Hungarian Revolution Portal. http://www.americanhungarianfederation.org/1956/photos.htm.

Jones, Frank. “The first time I met Ibi Gabori.” Toronto Star. 29 February 1992. K2. ProQuest. Web.

Józsa, Judit, and Tamás Pelles. La Storia della Scuola Italiana di Budapest alla Luce dei Documenti D’Archivio [The History of the Italan School of Budapest, in Light of Archival Documents]. http://web.t-online.hu/pellestamas/Tamas/bpoliskol.htm#_Toc189916144.

Kafka, Franz. “An Imperial Message.” Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir. The Complete Stories. New York: Schocken Books, 1971. 4–5.

Karinthy, Frigyes. “Chain-Links.” Translated by Adam Makkai, edited by Enikö Jankó. http://djjr-courses.wdfiles.com/local–files/soc180:karinthy-chain-links/Karinthy-Chain-Links_1929.pdf.

———. A Journey Round My Skull. New York: New York Review Books Classics, 2008.

———. Tanár úr kérem [Please Sir!]. Budapest: Dick Manó, 1916.

———. Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyageand Capillaria: Gulliver’s Sixth Voyage. Translated by Paul Tabori. London: New English Library, 1978.

Kearns, Lionel. By the Light of the Silvery McLune: Media Parables, Poems, Signs, Gestures, and Other Assaults on the Interface. Vancouver: Daylight Press, 1969.

Kieval, Hillel J. “Tiszaeszlár Blood Libel.” The Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. 2010. http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Tiszaeszlar_Blood_Libel.

Koehler, Robert. “Pantomimist Marcel Marceau in Performance at Segerstrom Hall.” Los Angeles Times, 11 February 1988. http://articles.latimes.com/1988-02-11/entertainment/ca-41839_1_marcel-marceau.

Kossar, Leon. “Canada Heaven for Hungarians.” The Telegram, 30 April 1957.

Kramer, Mark. “The Soviet Union and the 1956 Crises in Hungary and Poland: Reassessments and New Findings.” Journal of Contemporary History 33, no. 2 (April 1998): 163—214.

Lenvai, Paul. One Day That Shook the Communist World: The 1956 Hungarian Uprising and Its Legacy. Translated by Ann Major. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Leopardi, Giacomo. Canti. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2010.

Lloyd, John. Portrait of Robert Zend. Cover of Beyond Labels. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Toronto: Hounslow Press, 1982.

Luther, Claudia. “Marcel Marceau, 84; legendary mime was his art’s standard-bearer for seven decades.” Los Angeles Times, 24 September 2007. http://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/24/local/me-marceau24.

Madách, Imre. The Tragedy of Man. Translated by George Szirtes. New York: Puski Publishing,1988.

———. The Tragedy of Man. Translated and illustrated by Robert Zend.

Magritte, René. Le fils de l’homme. 1964. Magritte Foundation. http://www.magritte.be/portfolio-item/fils-de-l-homme-2/?lang=en.

———. Radio interview with Jean Neyens (1965), in Harry Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, translated by Richard Millen, 172. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1977.

———. Les valeurs personelles (Personal Values), Series 2. 1952. Magritte Foundation. http://www.magritte.be/portfolio-item/les-valeurs-personnelles/?lang=en.

The Maple Laugh Forever: An Anthology of Comic Canadian Poetry. Edited by Douglas Barbour and Stephen Scobie. Edmonton, Alberta: Hurtig Publishers, 1981.

Marceau, Marcel. Comments on front inner dust jacket of From Zero to One by Robert Zend. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Mission, BC: The Sono Nis Press, 1973.

———. Marceau, Marcel. “Marcel Marceau Paintings.” Encyclopedia of Mime. Available at http://www.mime.info/encyclopedia/marceau-paintings.html.

———. The Mask Maker./em> Available at http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7ffi4_marcel-marceau-le-masque_fun.

———. Portrait of Robert Zend. Drawing (medium unknown). Dust jacket cover of From Zero to One by Robert Zend. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Mission, BC: The Sono Nis Press, 1973.

———. “This Drawing, Poem, and Zend During and After.” In A Bouquet to Bip by Robert Zend. Exile Magazine 1, no. 3 ( 1973): 121-22.

———. Youth, Maturity, Old Age, and Death. Film stills from 1965 performance. Available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5RLTZSrr4A.

Marcus, Frank. “Marceau: The Second Phase.” The Transatlantic Review 11 (1962): 12—18.

Marinari, Umberto. Introduction. Pirandello’s Theatre of Living Masks. Translated by Umberto Mariani and Alice Gladstone Mariani. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. 3—26.

Martin, Camille. Entry on Lionel Kearns for The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2013. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/en/article/lionel-kearns/.

Messerli, Douglas. “Frigyes Karinthy.” Green Integer. The PIP (Project for Innovative Poetry) Blog. 30 November 2010. http://pippoetry.blogspot.ca/2010/11/frigyes-karinthy.html.

New Poems of the Seventies. Edited by Douglas Lochhead and Raymond Souster. Ottawa: Oberon Press, 1970.

New York Café, Budapest. Photograph. Available at Famous Coffee Houses. http://www.braunhousehold.com.

Nichol, B. P. The Alphabet Game: A bpNichol Reader. Edited by Darren Wershler-Henry and Lori Emerson. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007.

———. Art Facts: A Book of Contexts. Tucson: Chax Press, 1990.

———. “Calendar” (detail). Broadside. S.n, n.d.

———. Konfessions of an Elizabethan Fan Dancer. Toronto: Coach House Press, 2004; originally released in Canada in 1974.

———. The Martyrology, Book 6 Books. 1987; reprint. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1994.

———. The Martyrology 5. 1982; facsimile edition. Toronto: Coach House Books, 1994.

———. Meanwhile: The Critical Writings of bpNichol. Edited by Roy Miki. Vancouver: Talon Books, 2002.

———. Merry-Go-Round. Illustrated by Simon Ng. Red Deer, Alberta: Red Deer College Press, 1991.

———. Zygal: A Book of Mysteries and Translations. Toronto: Coach House Books, 1985.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “The Birth of Tragedy.” Basic Writings of Nietzsche. Translated and edited by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Modern Library, 2000. 1—144.

Nyugat 1938, no. 10. Budapest. Frigyes Karinthy memorial issue.

Pirandello, Luigi. Right You Are, If You Think You Are. In Pirandello’s Theatre of Living Masks. Translated by Umberto Mariani and Alice Gladstone Mariani. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. 69—118.

———. Six Characters in Search of an Author and Other Plays. Translated by Mark Musa. New York: Penguin Classics, 1996.

———. Six Characters in Search of an Author. In Pirandello’s Theatre of Living Masks. Translated by Umberto Mariani and Alice Gladstone Mariani. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. 119—67.

Priest, Robert, Robert Sward, and Robert Zend. The Three Roberts: On Childhood. St. Catherines, Ontario: Moonstone Press, 1985.

———. The Three Roberts: On Love. Toronto: Dreadnaught, 1984.

———. The Three Roberts: Premiere Performance. Scarborough, Ontario: HMS Press, 1984.

Q Art Theatre. The Tragedy of Man publicity poster. Montreal: Q Art Theatre, October – November 2000.

R., Patrick. Robert Zend. “Memorial.” http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=10862727.

Rippl-Rónai, József. Portrait of Frigyes Karinthy. 1925. Pastel. Petőfi Museum of Literature. Available from Terminartors. http://www.terminartors.com/artworkprofile/Rippl-Ronai_Jozsef-Portrait_of_Frigyes_Karinthy.

Robert Zend bio. Ronsdale Press. Available at http://ronsdalepress.com/authors/robert-zend/.

Robert Zend fonds. Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries, Toronto, Canada.

Sanders, Ivan. “Karinthy, Ferenc.” The Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. 2010. http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Karinthy_Ferenc

Six Degrees of Separation. 1993. DVD Culver City, Canada: MGM Home Entertainment, 2000.

Sled, Dmitri. “Partisans In The Arts: Marcel Marceau (1923—2007).” Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation. 12 June 2012. http://jewishpartisans.blogspot.ca/2012/06/partisans-in-arts-marcel-marceau-1923.html.

Standelsky, Eva, and Zoltan Volgyesl. Tainted Revolution. Dir. Martin Mevius. The Netherlands: Association for the Study of Nationalities, 2006.

Stark, Tamás. “‘Malenki Robot’ – Hungarian Forced Labourers in the Soviet Union (1944–1955).” Minorities Research: A Collection of Studies by Hungarian Authors. Edited by Győző Cholnoky. Budapest: Lucidus K., 1999. 155-167. http://www.epa.hu/00400/00463/00007/pdf/155_stark.pdf

Sterne, Laurence. Tristram Shandy. Edited by Howard Anderson. New York: W. W. Norton, 1980.

Szabó, László Cs. Qtd. in “Frigyes Karinthy Author’s Page.” Publishing Hungary. Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum. http://www.hunlit.hu/karinthyfrigyes,en.

Szaynok, Bożena. “Stalinization of Eastern Europe.” Translated by John Kulczycki. Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. Edited by Richard S. Levy. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2005. 677—80.

Talpalatnyi föld [Treasured Earth]. Directed by Frigyes Bán. Hungary: Magyar Filmgyártó Nemzeti Vállalat, 1948.

The Toronto Mirror. Published and edited by Robert Zend. October 1961.

Troper, Harold. “Canada and the Hungarian Refugees: The Historical Context.” In The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: Hungarian and Canadian Perspectives, edited by Christopher Adam, Tibor Egervari, Leslie Laczko, and Judy Young, 176—93. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2010.

Ungváry, Krisztián. The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II. Translated by Ladislaus Löb. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC. “Hungary after the German Occupation.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. Last modified 10 June 2013. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005458.

Veidlinger, Jeffrey. “Stalin, Joseph (1879—1953).” Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. Edited by Richard S. Levy. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2005. 676—77.

Volvox: Poetry from the Unofficial Languages of Canada . . . in English Translation. Edited by J. Michael Yates. The Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia: The Sono Nis Press, 1971.

Wershler, Darren. “News That Stays News: Marshall McLuhan and Media Poetics.” The Journal of Electronic Publishing 14 no. 2 (2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0014.208.

White, Norman T. “The Hearsay Project.” The NorMill. 11—12 November 1985. http://www.normill.ca/Text/Hearsay.txt.

Zend, Natalie. A Biography of Robert Zend. Unpublished manuscript. 8 March 1983. Personal library of Janine Zend.

Zend, Robert. Ararat. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Arbormundi: 16 Selected Typescapes. Vancouver: Blewointment Press, 1982.

———. Beyond Labels. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Toronto: Hounslow Press, 1982.

———. A Bouquet to Bip. Exile Magazine 1, no. 3 ( 1973): 93–123.

———. Dancers. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Daymares: Selected Fictions on Dreams and Time. Edited by Brian Wyatt. Vancouver: CACANADADADA Press, 1991.

———. Eden. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Fából vaskarikatúrák. Budapest: Magyar Világ Kiadó, 1993.

———. Film poster produced for Hamlet, directed by Lawrence Olivier (London: Two Cities Films, 1948). Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, 1948.

———. Film poster produced for Talpalatnyi föld (Treasured Earth), directed by Frigyes Bán (Hungary: Magyar Filmgyártó Nemzeti Vállalat, 1948). Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, 1948.

———. From Zero to One. Translated by Robert Zend and John Robert Colombo. Mission, BC: The Sono Nis Press, 1973.

———. Genesis. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Hazám törve kettővel. Montréal: Omnibooks, 1991.

———. Heavenly Cocktail Party. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. How Do Yoo Doodle?. Unpublished manuscript. Private collection of Janine Zend. Coloration is the author’s.

———. “The Key.” Exile Magazine 2, no. 2 (1974): 57-67.

———. LineLife. Ink drawing on paper. 1983. Box 10, Robert Zend fonds, Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries. Adapted for digital medium by Camille Martin.

———. “Months of the Super-Year.” Exile Magazine 2, no. 2 (1974): 50.

———. Nicolette: A Novel Novel. Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 1993.

———. Oāb. Volume 1. Toronto: Exile Editions, 1983.

———. Oāb. Volume 2. Toronto: Exile Editions, 1985.

———. Pirandello and the Number Two. Master’s thesis. University of Toronto, 1969.

———. Polinear No. 3. 1982. Ink on paper. Private collection.

———. Quadriptych in Gasquette series. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Science Fiction. N.d. Paper collage. Private collection.

———. Toiletters. N.d. Ink on toilet paper rolls. Private collection.

———. “Type Scapes: A Mystery Story.” Exile Magazine 5 nos. 3-4 (1978): 147.

———. Versek, Képversek. Párizs: Magyar mühely, 1988.

———. Windmill. N.d. Mixed media with thumbtacks, sewing pins, string, and paper on wood. Private collection.

———. “The World’s Greatest Poet.” Exile Magazine 2, no. 2 (1974): 55-56.

———. Zendocha-land. Unpublished manuscript, 1979.

Zend, Robert, ed. Vidám úttörő nyár (Happy Summer Pioneers). Magyar Úttörők Szövetsége (Association of Hungarian Pioneers), 1955.

Zend, Robert, translator and illustrator. The Tragedy of Man by Imre Madách. Unpublished manuscript.

Zend, Robert, and Jerónimo. My friend, Jerónimo. Toronto: Omnibooks, 1981.

“Zend, Robert.” Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. Edited by W. H. New. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002. 1234.

Camille Martin

Magritte’s Les Valeurs personelles (Personal Values) (fig. 3) is possibly the work that inspired Zend’s “Climate.” Like Zend’s poem, Magritte’s still life discombobulates the viewer’s sense of indoors and outdoors, and it subverts the normal utility of objects, as in the giant comb and wine glass. Magritte’s surrealism disturbs the normal context of objects (indoors becomes outdoors; small becomes gigantic), a feature of his work that informs Zend’s self-referential poem.

Magritte’s Les Valeurs personelles (Personal Values) (fig. 3) is possibly the work that inspired Zend’s “Climate.” Like Zend’s poem, Magritte’s still life discombobulates the viewer’s sense of indoors and outdoors, and it subverts the normal utility of objects, as in the giant comb and wine glass. Magritte’s surrealism disturbs the normal context of objects (indoors becomes outdoors; small becomes gigantic), a feature of his work that informs Zend’s self-referential poem.

Zend describes Leopardi as “one of the greatest Italian poets; also one of the most pessimistic poets of world literature.”

Zend describes Leopardi as “one of the greatest Italian poets; also one of the most pessimistic poets of world literature.” Luigi Pirandello (fig. 2) is an Italian playwright whose writing is perhaps closer in spirit to Zend’s work than the despairing Leopardi.

Luigi Pirandello (fig. 2) is an Italian playwright whose writing is perhaps closer in spirit to Zend’s work than the despairing Leopardi. Zend, who had the unusual ability to visualize texts as diagrams or glyphs (as we saw in the installment on Borges), offers in his thesis diagrams showing the complex network of doubling among Pirandello’s characters, such as those in a short story in the collection Novelle per un anno (fig. 3).

Zend, who had the unusual ability to visualize texts as diagrams or glyphs (as we saw in the installment on Borges), offers in his thesis diagrams showing the complex network of doubling among Pirandello’s characters, such as those in a short story in the collection Novelle per un anno (fig. 3).

They shared a keen sense of humour and apparently also a love of the spontaneous sketch: Zend calls Marceau “a friend with whom I like doodling together.”

They shared a keen sense of humour and apparently also a love of the spontaneous sketch: Zend calls Marceau “a friend with whom I like doodling together.”

Marceau’s compressed arc of human life is reminiscent of Zend’s typescape Mutamus (We Are Changing) (fig. 5), which shows five stages of human life against the backdrop of an hourglass. It also recalls Zend’s 1983 flipbook animation entitled Linelife, which I featured in Part 1. of this series, and which I repeat below for any who missed it or would like to see it again (fig. 6):

Marceau’s compressed arc of human life is reminiscent of Zend’s typescape Mutamus (We Are Changing) (fig. 5), which shows five stages of human life against the backdrop of an hourglass. It also recalls Zend’s 1983 flipbook animation entitled Linelife, which I featured in Part 1. of this series, and which I repeat below for any who missed it or would like to see it again (fig. 6): The flip side of that universalism is Zend’s interest in Marceau’s renditions of masking and of the divided self. In one style sketch, Bip plays a mask maker who alternately tries on his masks of tragedy and comedy, performing various antics appropriate to the masks’ moods. But at a certain point he’s unable to remove the laughing mask. As Bip grows increasingly desperate to pry it off, his frantic gestures reveal the stark incongruity between the laughing mask and the tragedy of the situation (fig. 7). Finally, Bip blinds himself and is then able to peel off the offending mask. Marceau describes the sketch of the Mask Maker as showing, “through the use of his many faces, the problem of illusion and reality,” thus creating a “Pirandellian effect,”

The flip side of that universalism is Zend’s interest in Marceau’s renditions of masking and of the divided self. In one style sketch, Bip plays a mask maker who alternately tries on his masks of tragedy and comedy, performing various antics appropriate to the masks’ moods. But at a certain point he’s unable to remove the laughing mask. As Bip grows increasingly desperate to pry it off, his frantic gestures reveal the stark incongruity between the laughing mask and the tragedy of the situation (fig. 7). Finally, Bip blinds himself and is then able to peel off the offending mask. Marceau describes the sketch of the Mask Maker as showing, “through the use of his many faces, the problem of illusion and reality,” thus creating a “Pirandellian effect,” Following Marceau’s visit, Zend and Marceau continued their expression of friendship and mutual esteem. Marceau expressed his admiration of Zend in both words and art. He wrote that “[o]nce Robert Zend told me that I was a poet of gestures. Once I told him he was a mime with words. Robert Zend is a poet in every moment of his life.”

Following Marceau’s visit, Zend and Marceau continued their expression of friendship and mutual esteem. Marceau expressed his admiration of Zend in both words and art. He wrote that “[o]nce Robert Zend told me that I was a poet of gestures. Once I told him he was a mime with words. Robert Zend is a poet in every moment of his life.” After designing the chess set, Zend again paid tribute to Marceau in a thirty-one-page piece entitled A Bouquet to Bip, published in Exile Magazine in 1973 (fig. 9). The bouquet in the title likely refers to the single red flower absurdly sprouting from Bip’s crumpled opera hat. We have already seen some text from A Bouquet to Bip above. The following are some remarkable images from that sequence.

After designing the chess set, Zend again paid tribute to Marceau in a thirty-one-page piece entitled A Bouquet to Bip, published in Exile Magazine in 1973 (fig. 9). The bouquet in the title likely refers to the single red flower absurdly sprouting from Bip’s crumpled opera hat. We have already seen some text from A Bouquet to Bip above. The following are some remarkable images from that sequence.

The reader of Zend’s short stories in Daymares is likely to notice that they are on a similar wavelength as the fantastical fiction of Borges. Using surreal, mythical, or dream-like settings, both explore philosophical and metafictive concepts, toy with notions of infinity, expand the limits of human cognition, and posit labyrinthine or paradoxical quandaries, leaving the reader with a feeling that there is a mystery at the heart of existence and the universe that will not yield to rational analysis. Zend was already writing in a fantastical vein when in the early 1970s he began reading Borges and working on a CBC Ideas program entitled “The Magic World of Borges.” Lawrence Day, a member of the chess club that Zend frequented, describes how the idea came about:

The reader of Zend’s short stories in Daymares is likely to notice that they are on a similar wavelength as the fantastical fiction of Borges. Using surreal, mythical, or dream-like settings, both explore philosophical and metafictive concepts, toy with notions of infinity, expand the limits of human cognition, and posit labyrinthine or paradoxical quandaries, leaving the reader with a feeling that there is a mystery at the heart of existence and the universe that will not yield to rational analysis. Zend was already writing in a fantastical vein when in the early 1970s he began reading Borges and working on a CBC Ideas program entitled “The Magic World of Borges.” Lawrence Day, a member of the chess club that Zend frequented, describes how the idea came about: Zend indeed took full advantage of the opportunities afforded him by his role as producer at CBC by traveling around the world interviewing persons who made important contributions to culture and science. And by doing so he made a lasting contribution to Canadian intellectual life. In Hungary, his travel opportunities had been limited and closely monitored for signs of the intention to defect. After he finally escaped and immigrated to Canada in 1956, it was as though his pent-up desire to travel the world and meet other writers were suddenly given the freedom and means to be fulfilled.

Zend indeed took full advantage of the opportunities afforded him by his role as producer at CBC by traveling around the world interviewing persons who made important contributions to culture and science. And by doing so he made a lasting contribution to Canadian intellectual life. In Hungary, his travel opportunities had been limited and closely monitored for signs of the intention to defect. After he finally escaped and immigrated to Canada in 1956, it was as though his pent-up desire to travel the world and meet other writers were suddenly given the freedom and means to be fulfilled.

This type of visualization of a narrative line or pattern is reminiscent of Laurence Sterne’s illustrations of meandering lines in Tristram Shandy to render visible the novel’s digressive texture (fig. 4). Interestingly, in both works, the visually reflexive gestures serve both as digressions within a digressive story and as further deferrals of the novel’s professed autobiographical subject. Shandy early in the novel sets his metanarrative cards on the table: “digressions are the sunshine; — they are the life, the soul of reading!”

This type of visualization of a narrative line or pattern is reminiscent of Laurence Sterne’s illustrations of meandering lines in Tristram Shandy to render visible the novel’s digressive texture (fig. 4). Interestingly, in both works, the visually reflexive gestures serve both as digressions within a digressive story and as further deferrals of the novel’s professed autobiographical subject. Shandy early in the novel sets his metanarrative cards on the table: “digressions are the sunshine; — they are the life, the soul of reading!” As part of his exploration of the process of “The Key,” Zend displays his visualization of the story’s metafictive pattern as an Escher-like paradox (fig. 5). Any two angles of the triangular sculpture constitute a logically possible shape; the addition of the third angle makes the form impossible as a three-dimensional object. Although Zend does not explain the corresponding irrational concept of the meta-meta-narrative of “The Key,” he is clearly, in works such as Oāb, fascinated by other such topological conundrums as the Klein bottle and the Möbius strip, which don’t lead anywhere but their own infinitely repeating surface. Somewhat similarly, the irrational triangle creates an endlessly iterable and labyrinthine path, corresponding to the journey of the story that never reaches its supposed destination (the planned narrative about a key to a labyrinth), but instead becomes the labyrinth itself for which the reader must search for a key within her- or himself.

As part of his exploration of the process of “The Key,” Zend displays his visualization of the story’s metafictive pattern as an Escher-like paradox (fig. 5). Any two angles of the triangular sculpture constitute a logically possible shape; the addition of the third angle makes the form impossible as a three-dimensional object. Although Zend does not explain the corresponding irrational concept of the meta-meta-narrative of “The Key,” he is clearly, in works such as Oāb, fascinated by other such topological conundrums as the Klein bottle and the Möbius strip, which don’t lead anywhere but their own infinitely repeating surface. Somewhat similarly, the irrational triangle creates an endlessly iterable and labyrinthine path, corresponding to the journey of the story that never reaches its supposed destination (the planned narrative about a key to a labyrinth), but instead becomes the labyrinth itself for which the reader must search for a key within her- or himself. Considering the literary kinship of Borges and Zend, their friendship and mutual esteem is not surprising. Zend didn’t hesitate to fly thousands of miles to meet a writer whose work resonated with his own. He realized that Borges’ fiction could serve as inspiration, and indeed, the spirit of Borges’ can be seen in Zend’s fantastical work that blossomed in the stories, poems, and artworks of Daymares, a good portion of which were written following his meeting with Borges.

Considering the literary kinship of Borges and Zend, their friendship and mutual esteem is not surprising. Zend didn’t hesitate to fly thousands of miles to meet a writer whose work resonated with his own. He realized that Borges’ fiction could serve as inspiration, and indeed, the spirit of Borges’ can be seen in Zend’s fantastical work that blossomed in the stories, poems, and artworks of Daymares, a good portion of which were written following his meeting with Borges.

Similarly, Zend tells that he came to typewriter art with no knowledge of precedents. By 1978, he had already produced a body of work in the category of concrete poetry, and was approached by John Jessop to contribute to the International Anthology of Concrete Poetry he was editing. Jessop selected forty, some of which needed to be re-typed or translated from the Hungarian original.

Similarly, Zend tells that he came to typewriter art with no knowledge of precedents. By 1978, he had already produced a body of work in the category of concrete poetry, and was approached by John Jessop to contribute to the International Anthology of Concrete Poetry he was editing. Jessop selected forty, some of which needed to be re-typed or translated from the Hungarian original.

Both Zend and Nichol delighted in alphabet games, including the creation of artificial alphabets and strange fonts. Zend’s playful use of the alphabet in the visual poetry of Oāb is related to Nichol’s concrete poetry experimentations using the letters of the alphabet, giving sculptural materiality and playful drama to the irreducible components of language. Fig. 12 is an example of Nichol using comic-book-like frames, riffing on the letter “A.” Fig. 13 shows images from three pages in Oāb, in which names and letters personify the characters they represent, playing out various dramas in Zend’s myth of authorial creation—sometimes also using comic-book frames for the parade of Oāb and Ïrdu’s games.

Both Zend and Nichol delighted in alphabet games, including the creation of artificial alphabets and strange fonts. Zend’s playful use of the alphabet in the visual poetry of Oāb is related to Nichol’s concrete poetry experimentations using the letters of the alphabet, giving sculptural materiality and playful drama to the irreducible components of language. Fig. 12 is an example of Nichol using comic-book-like frames, riffing on the letter “A.” Fig. 13 shows images from three pages in Oāb, in which names and letters personify the characters they represent, playing out various dramas in Zend’s myth of authorial creation—sometimes also using comic-book frames for the parade of Oāb and Ïrdu’s games.

Another dimension to Zend’s multi-genre explorations is his sound poetry. In addition to composing and performing his own, sometimes in collaboration with others, Zend also performed on at least one occasion, according to Janine Zend, with The Four Horsemen, the sound poetry group to which bpNichol belonged along with Steve McCaffery, Rafael Barreto-Rivera, and Paul Dutton.

Another dimension to Zend’s multi-genre explorations is his sound poetry. In addition to composing and performing his own, sometimes in collaboration with others, Zend also performed on at least one occasion, according to Janine Zend, with The Four Horsemen, the sound poetry group to which bpNichol belonged along with Steve McCaffery, Rafael Barreto-Rivera, and Paul Dutton.

One of the most striking (and most widely anthologized) works from By the Light of the Silvery McLune is the concrete poem “The Birth of God” (fig. 2), which Kearns calls “a mathematical mandela embodying the perfect creative/destructive principle of the mutual interpenetration and balanced interdependence of opposites.” In its creation of an image of the binary from characters that denote the binary system, it might well also be an homage to McLuhan.

One of the most striking (and most widely anthologized) works from By the Light of the Silvery McLune is the concrete poem “The Birth of God” (fig. 2), which Kearns calls “a mathematical mandela embodying the perfect creative/destructive principle of the mutual interpenetration and balanced interdependence of opposites.” In its creation of an image of the binary from characters that denote the binary system, it might well also be an homage to McLuhan.

Imre Madách is the Milton of Hungary. Just as the English-speaking literary world is well acquainted with Paradise Lost, almost every Hungarian is familiar with Madách’s The Tragedy of Man (1861), a long dramatic poem that takes as its starting point the story of creation and the Garden of Eden in Genesis (fig. 2).

Imre Madách is the Milton of Hungary. Just as the English-speaking literary world is well acquainted with Paradise Lost, almost every Hungarian is familiar with Madách’s The Tragedy of Man (1861), a long dramatic poem that takes as its starting point the story of creation and the Garden of Eden in Genesis (fig. 2).

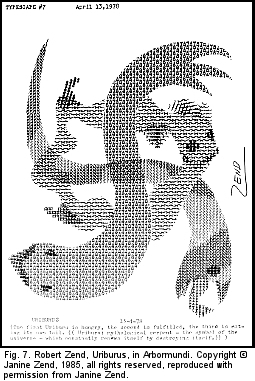

And the typescape Uriburus (fig. 7) intertwines three images of the ancient serpent of world mythology in various stages of a cyclical process of beginnings and endings: “The first uriburu is hungry, the second is fulfilled, the third is eating its own tail.” Zend notes that the serpents symbolize “the universe — which constantly renews itself by destroying itself.”

And the typescape Uriburus (fig. 7) intertwines three images of the ancient serpent of world mythology in various stages of a cyclical process of beginnings and endings: “The first uriburu is hungry, the second is fulfilled, the third is eating its own tail.” Zend notes that the serpents symbolize “the universe — which constantly renews itself by destroying itself.” Such was Zend’s admiration for Madách’s The Tragedy of Man that after he immigrated to Canada and became fluent in English, he wrote a translation of it, which he later edited with Peter Singer and illustrated with works by an unidentified artist (fig. 8). He wanted to create an English version with more contemporary language, as opposed to the British translations in somewhat outdated English that were available at the time.

Such was Zend’s admiration for Madách’s The Tragedy of Man that after he immigrated to Canada and became fluent in English, he wrote a translation of it, which he later edited with Peter Singer and illustrated with works by an unidentified artist (fig. 8). He wanted to create an English version with more contemporary language, as opposed to the British translations in somewhat outdated English that were available at the time.

If Madách is Hungary’s Milton, then Karinthy is its Jonathan Swift (fig. 10). His sketches, stories, and novels are known for their satirical qualities, and he was an important science fiction/fantasy writer under the sign of Swift.

If Madách is Hungary’s Milton, then Karinthy is its Jonathan Swift (fig. 10). His sketches, stories, and novels are known for their satirical qualities, and he was an important science fiction/fantasy writer under the sign of Swift. Karinthy belongs to the generation known as “Nyugat” (West), named after the Budapest literary journal in which they were frequently published. Fig. 11 shows the Karinthy memorial issue of Nyugat, published shortly after Karinthy’s death in 1938. This issue also includes poems in a series entitled Postcards by Miklós Radnóti, a Hungarian poet and victim of the Holocaust, whose work Zend also greatly admired.

Karinthy belongs to the generation known as “Nyugat” (West), named after the Budapest literary journal in which they were frequently published. Fig. 11 shows the Karinthy memorial issue of Nyugat, published shortly after Karinthy’s death in 1938. This issue also includes poems in a series entitled Postcards by Miklós Radnóti, a Hungarian poet and victim of the Holocaust, whose work Zend also greatly admired. The “energetic arguing” reveals something of Karinthy’s intellectual milieu in Budapest: the gathering of literati and their acolytes in cafés to debate, exchange stories, and hone their wit with verbal play. Douglas Messerli likens this café culture to that of the New York Algonquin writers, and states that Karinthy and other writers “held literary court at the famed Budapest New York Café” (fig. 12), where they “played sophisticated verbal games and satirized the leading Hungarian poets.”

The “energetic arguing” reveals something of Karinthy’s intellectual milieu in Budapest: the gathering of literati and their acolytes in cafés to debate, exchange stories, and hone their wit with verbal play. Douglas Messerli likens this café culture to that of the New York Algonquin writers, and states that Karinthy and other writers “held literary court at the famed Budapest New York Café” (fig. 12), where they “played sophisticated verbal games and satirized the leading Hungarian poets.”

The Zends, who had been living at subsistence level in Budapest and in fleeing lost whatever meagre possessions they owned, benefited from the new, more lenient and generous refugee policies. On December 11 in Liverpool, along with 106 other Hungarian refugees and hundreds of regular passengers,

The Zends, who had been living at subsistence level in Budapest and in fleeing lost whatever meagre possessions they owned, benefited from the new, more lenient and generous refugee policies. On December 11 in Liverpool, along with 106 other Hungarian refugees and hundreds of regular passengers,

Finally they arrived in Halifax on December 22. On their landing cards (fig. 5), Zend indicates his profession as reporter-journalist, and Ibi as librarian. Their religion is noted as Presbyterian. Considering the Nazi terror that Hungarians had experienced, it’s not difficult to understand the concealing of Ibi’s Jewish background, also keeping in mind that antisemitism was not limited to its long history in Europe but was also present and indeed institutionalized in Canada during the 1950s, as we have seen from the prejudice of the Canadian director of immigration. In addition, Jewish quotas and stricter admission standards were in place for universities such as McGill and the University of Toronto.

Finally they arrived in Halifax on December 22. On their landing cards (fig. 5), Zend indicates his profession as reporter-journalist, and Ibi as librarian. Their religion is noted as Presbyterian. Considering the Nazi terror that Hungarians had experienced, it’s not difficult to understand the concealing of Ibi’s Jewish background, also keeping in mind that antisemitism was not limited to its long history in Europe but was also present and indeed institutionalized in Canada during the 1950s, as we have seen from the prejudice of the Canadian director of immigration. In addition, Jewish quotas and stricter admission standards were in place for universities such as McGill and the University of Toronto. In Halifax, they boarded a train for Toronto. From the photographs Zend took from the train, his fascination with the vast stretches of snow, punctuated by a cluster of houses every few hours, is apparent (fig. 6). He and Ibi joked wryly that the landscape might well be Siberian — except of course for the occasional church steeple rising above a village.

In Halifax, they boarded a train for Toronto. From the photographs Zend took from the train, his fascination with the vast stretches of snow, punctuated by a cluster of houses every few hours, is apparent (fig. 6). He and Ibi joked wryly that the landscape might well be Siberian — except of course for the occasional church steeple rising above a village. The Toronto population mobilized to provide housing and jobs for the new refugees to help them get started. From January to March 1957, a couple in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke gave the Zends a place to live in exchange for Ibi’s labour as a live-in domestic (fig. 7). Meanwhile, Robert put his experience in the Hungarian film industry to use when he found work at Chatwynd Studios editing film and doing odd jobs while he learned English. Soon thereafter, Ibi was able to find a job in her field as a librarian at the Toronto Public Library. Robert and Ibi were pleased to find that even on their low income during the first few years in Canada, they were able to afford things that were out of their reach in Hungary because either supplies were short or they couldn’t afford them. Aniko, who was born premature and who was sickly and undernourished the first eight months of her life , received the special nutrition she needed to flourish.

The Toronto population mobilized to provide housing and jobs for the new refugees to help them get started. From January to March 1957, a couple in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke gave the Zends a place to live in exchange for Ibi’s labour as a live-in domestic (fig. 7). Meanwhile, Robert put his experience in the Hungarian film industry to use when he found work at Chatwynd Studios editing film and doing odd jobs while he learned English. Soon thereafter, Ibi was able to find a job in her field as a librarian at the Toronto Public Library. Robert and Ibi were pleased to find that even on their low income during the first few years in Canada, they were able to afford things that were out of their reach in Hungary because either supplies were short or they couldn’t afford them. Aniko, who was born premature and who was sickly and undernourished the first eight months of her life , received the special nutrition she needed to flourish. And for the first time in his life, Robert was able to afford a typewriter. In Hungary, it would have cost three months’ wages, but in Toronto he only needed to put a dollar down and pay affordable installments.

And for the first time in his life, Robert was able to afford a typewriter. In Hungary, it would have cost three months’ wages, but in Toronto he only needed to put a dollar down and pay affordable installments. In addition to writing of feelings of alienation, Zend, profoundly affected by the sudden and unexpected immigration, wrote “about the change, the culture shock, the homesickness, about the schizoid emotions of an exile between two worlds.”

In addition to writing of feelings of alienation, Zend, profoundly affected by the sudden and unexpected immigration, wrote “about the change, the culture shock, the homesickness, about the schizoid emotions of an exile between two worlds.” Some of Zend’s concrete poetry such as “BUDAPESTORONTO” (fig. 10) graphically epitomizes his complex and conflicted feelings about the two cities: Budapest, cosmopolitan and cultured yet also a place where intellectuals were censored and oppressed, and sometimes in danger for their lives; versus relatively “prosaic” Toronto, as Zend puts it in “Return Tickets” — “huge, clean, and functional.”

Some of Zend’s concrete poetry such as “BUDAPESTORONTO” (fig. 10) graphically epitomizes his complex and conflicted feelings about the two cities: Budapest, cosmopolitan and cultured yet also a place where intellectuals were censored and oppressed, and sometimes in danger for their lives; versus relatively “prosaic” Toronto, as Zend puts it in “Return Tickets” — “huge, clean, and functional.”

And his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. At that time, there were no Hungarian ethnic literary publications in Canada. So for about a year in 1961, he published his own Hungarian literary monthly, The Toronto Mirror (fig. 12). However, his advertisers, “unable to think but in labels,” wanted to know whether his publication was for “leftists or rightists, for Catholics or Protestants, for Jews or Gendarmes, for junior or senior citizens.”

And his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. At that time, there were no Hungarian ethnic literary publications in Canada. So for about a year in 1961, he published his own Hungarian literary monthly, The Toronto Mirror (fig. 12). However, his advertisers, “unable to think but in labels,” wanted to know whether his publication was for “leftists or rightists, for Catholics or Protestants, for Jews or Gendarmes, for junior or senior citizens.” On the positive side, life in Toronto was relatively peaceful and stable, and provided a safe haven for Zend to continue his development as a writer (fig. 13). In a 1959 letter to Pierre Berton, he professes that with some reservations, he “likes Canada very much. Not because I am living here and this has become my second homeland,” but because it represents freedom, which is his “first homeland” for which he was “homesick . . . already in Hungary.” As much as he loved the land and language of his birth, it was also a country scarred by history and suffering under an oppressive regime intolerant of free expression. In a letter to the editor soon after his arrival, he writes that in the Soviet Union and its satellite countries,

On the positive side, life in Toronto was relatively peaceful and stable, and provided a safe haven for Zend to continue his development as a writer (fig. 13). In a 1959 letter to Pierre Berton, he professes that with some reservations, he “likes Canada very much. Not because I am living here and this has become my second homeland,” but because it represents freedom, which is his “first homeland” for which he was “homesick . . . already in Hungary.” As much as he loved the land and language of his birth, it was also a country scarred by history and suffering under an oppressive regime intolerant of free expression. In a letter to the editor soon after his arrival, he writes that in the Soviet Union and its satellite countries, In 1967, Zend decided to continue his studies in Italian literature by pursuing a Master of Arts degree at the University of Toronto. First, however, he needed to give evidence that he had earned a bachelor’s degree in Hungary. Returning for the first time to Hungary since 1956, he was able to retrieve his university diploma. While he was studying toward his degree, he continued working at the CBC in Original Film Editing, again making use of the skills he had learned in Hungary. After passing his oral examinations In Medieval Italian Literature, Italian Lyric Poetry from Petrarch to Marino, nineteenth-century Italian Poetry, and Luigi Pirandello, he graduated in spring 1969 (fig. 14).

In 1967, Zend decided to continue his studies in Italian literature by pursuing a Master of Arts degree at the University of Toronto. First, however, he needed to give evidence that he had earned a bachelor’s degree in Hungary. Returning for the first time to Hungary since 1956, he was able to retrieve his university diploma. While he was studying toward his degree, he continued working at the CBC in Original Film Editing, again making use of the skills he had learned in Hungary. After passing his oral examinations In Medieval Italian Literature, Italian Lyric Poetry from Petrarch to Marino, nineteenth-century Italian Poetry, and Luigi Pirandello, he graduated in spring 1969 (fig. 14). Seventeen years after his first poetry collection was to have been published in Hungary but instead tragically perished in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of 1956, Zend’s first collection of poems in English, From Zero to One, was published in 1973 by The Sono Nis Press in British Columbia (fig. 15). These poems were written between 1960 and 1969, and as he was still making the transition to writing poetry in English during that time, they were written in Hungarian and translated into English in collaboration with Colombo. In his first major statement as a poet we can already sense his cosmopolitan openness evidenced by the international influences in the poems and by his dedications to writers and artists from several countries (I’ll document these influences in greater detail starting with the next installment). Zend explores most of the major themes that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life: exile, science-fiction and fantasy, the metapoetic idea of the writer as creator, romantic love, and the cycle of birth and death. Evident throughout is his philosophical bent and his sense of irony and playfulness.

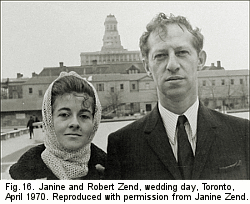

Seventeen years after his first poetry collection was to have been published in Hungary but instead tragically perished in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of 1956, Zend’s first collection of poems in English, From Zero to One, was published in 1973 by The Sono Nis Press in British Columbia (fig. 15). These poems were written between 1960 and 1969, and as he was still making the transition to writing poetry in English during that time, they were written in Hungarian and translated into English in collaboration with Colombo. In his first major statement as a poet we can already sense his cosmopolitan openness evidenced by the international influences in the poems and by his dedications to writers and artists from several countries (I’ll document these influences in greater detail starting with the next installment). Zend explores most of the major themes that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life: exile, science-fiction and fantasy, the metapoetic idea of the writer as creator, romantic love, and the cycle of birth and death. Evident throughout is his philosophical bent and his sense of irony and playfulness. By 1972, Zend had finished his coursework for the Ph.D. but stopped short of completing his dissertation. His personal life was in a period of transition around this time with the dissolultion of his marriage with Ibi and his starting a new family with Janine Devoize, who had immigrated from France to Canada in 1964 and whom he married in 1970 (fig. 16). For her part, after the divorce, Ibi married writer George Gabori, a fellow Hungarian survivor of a Nazi concentration camp, whom Zend had introduced to her. Gabori was also a survivor of Soviet labour camps and wrote a remarkable autobiographical account of his experiences, When Evils Were Most Free (1981). A friend relates that on the occasion of their marriage, Zend thought it “wonderful that his and Ibi’s daughter, Aniko, now had two fathers.”

By 1972, Zend had finished his coursework for the Ph.D. but stopped short of completing his dissertation. His personal life was in a period of transition around this time with the dissolultion of his marriage with Ibi and his starting a new family with Janine Devoize, who had immigrated from France to Canada in 1964 and whom he married in 1970 (fig. 16). For her part, after the divorce, Ibi married writer George Gabori, a fellow Hungarian survivor of a Nazi concentration camp, whom Zend had introduced to her. Gabori was also a survivor of Soviet labour camps and wrote a remarkable autobiographical account of his experiences, When Evils Were Most Free (1981). A friend relates that on the occasion of their marriage, Zend thought it “wonderful that his and Ibi’s daughter, Aniko, now had two fathers.” In 1972, a daughter, Natalie, was born to Robert and Janine (fig. 17). Natalie remembers her father as devoted, and one of her happiest memories is of the bedtime stories he would tell her from the time she was two years old. She recalls being delighted with tales that he gradually unfurled in series that lasted months, including a fantasy novel about Atlantis, Bible stories, world history, and stories from his childhood.

In 1972, a daughter, Natalie, was born to Robert and Janine (fig. 17). Natalie remembers her father as devoted, and one of her happiest memories is of the bedtime stories he would tell her from the time she was two years old. She recalls being delighted with tales that he gradually unfurled in series that lasted months, including a fantasy novel about Atlantis, Bible stories, world history, and stories from his childhood.

Eventually, the obsession subsided, and the typewriter wasn’t “a musical instrument any longer: it was a boring grey piece of metal mainly for correspondence. . . . I was fed up with paper and scotch tape, with scissors and shapes, with typing and patterns. I was fed up with my aching back and my strained eyes.” But during this brief period he had mastered his techniques and produced an astonishing number and variety of typescapes that are so beautifully executed as to leave the viewer surprised that such work was possible before the digital age. Zend collected and published some of the most polished of these works in Arbormundi (Tree of the World) (1982), a portfolio of sixteen typescapes (fig. 19).

Eventually, the obsession subsided, and the typewriter wasn’t “a musical instrument any longer: it was a boring grey piece of metal mainly for correspondence. . . . I was fed up with paper and scotch tape, with scissors and shapes, with typing and patterns. I was fed up with my aching back and my strained eyes.” But during this brief period he had mastered his techniques and produced an astonishing number and variety of typescapes that are so beautifully executed as to leave the viewer surprised that such work was possible before the digital age. Zend collected and published some of the most polished of these works in Arbormundi (Tree of the World) (1982), a portfolio of sixteen typescapes (fig. 19).

Zend wrote the poems in Beyond Labels (fig. 22) over a twenty-year span between 1962 and 1982; most were originally written in Hungarian and translated into English with the assistance of Colombo. They extend the theme of displacement, and in addition to including poems of a personal nature, he continues philosophical and cosmic concerns with poems about the universe, time, and dreams — as in one about an hourglass with infinite top and bottom. He also branches out formally with some early experiments in concrete poetry that he called “ditto” and “drop” poems. In dedications and influences, as well as the Magritte-inspired cover by John Lloyd, Beyond Labels continues the cosmopolitan flavour of his first collection.

Zend wrote the poems in Beyond Labels (fig. 22) over a twenty-year span between 1962 and 1982; most were originally written in Hungarian and translated into English with the assistance of Colombo. They extend the theme of displacement, and in addition to including poems of a personal nature, he continues philosophical and cosmic concerns with poems about the universe, time, and dreams — as in one about an hourglass with infinite top and bottom. He also branches out formally with some early experiments in concrete poetry that he called “ditto” and “drop” poems. In dedications and influences, as well as the Magritte-inspired cover by John Lloyd, Beyond Labels continues the cosmopolitan flavour of his first collection. Zend’s magnum opus is generally recognized to be the two-volume Oāb, published in 1983 and 1985 (fig. 23). Oāb is a multi-genre fantasy about authorship and creation, involving autobiography, metafiction, concrete poetry, drawings, and doodlings. “Ze̊nd,” a character in Zend’s own creation myth, writes a being named Oāb into existence and gives his progeny the “Alphoābet” to play with. And Oāb proceeds to do just that, in comic-book frames that show his growing knowledge and abilities. Oāb in turn creates a being named Ïrdu. Together they romp across the pages like children on a playground, creating a compendium of games and puzzles using the letters in their names to create shapes and explore their universe. The effect of this alphabetic creation is encyclopedic.

Zend’s magnum opus is generally recognized to be the two-volume Oāb, published in 1983 and 1985 (fig. 23). Oāb is a multi-genre fantasy about authorship and creation, involving autobiography, metafiction, concrete poetry, drawings, and doodlings. “Ze̊nd,” a character in Zend’s own creation myth, writes a being named Oāb into existence and gives his progeny the “Alphoābet” to play with. And Oāb proceeds to do just that, in comic-book frames that show his growing knowledge and abilities. Oāb in turn creates a being named Ïrdu. Together they romp across the pages like children on a playground, creating a compendium of games and puzzles using the letters in their names to create shapes and explore their universe. The effect of this alphabetic creation is encyclopedic. Daymares (1991), a collection of mostly short stories but also a few poems and concrete poems, selected by Janine, reveals Zend’s most extended and sophisticated expression of the fantastical, especially dream-worlds (fig. 24). Shape-shifting characters, dreams within dreams, anachronisms, and paradoxes keep the reader adrift in a fantastical realm whose often dark irrationality probes mysteries of humanity: uncharted cognitive depths, the burdens of history, and the continuities between self and other. These stories are akin to the mind-bending labyrinths and dreamscapes of Jorge Luis Borges.

Daymares (1991), a collection of mostly short stories but also a few poems and concrete poems, selected by Janine, reveals Zend’s most extended and sophisticated expression of the fantastical, especially dream-worlds (fig. 24). Shape-shifting characters, dreams within dreams, anachronisms, and paradoxes keep the reader adrift in a fantastical realm whose often dark irrationality probes mysteries of humanity: uncharted cognitive depths, the burdens of history, and the continuities between self and other. These stories are akin to the mind-bending labyrinths and dreamscapes of Jorge Luis Borges. Nicolette: A Novel Novel (1993) is an erotic avant-garde novel that Zend wrote in Hungarian in 1976 and translated into English (fig. 25). The temporally zigzagging narrative tells of a Toronto poet’s passionate and obsessive love affair with Nicolette, a woman half his age and the wife of a close friend, during visits to Paris and Florence. Not only is the chronology fractured, like a shifting, multi-layered dream, but also the chapters exploit a spectrum of forms and genres, playfully manifesting pieces of the story as haiku, Morse code, concrete poetry, a footnote, a play, epistolary narrative, Greek mythology, lyric poetry, censored text, and so forth. The novel also metafictively relates its own composition and birth: Nicolette from Nicolette.

Nicolette: A Novel Novel (1993) is an erotic avant-garde novel that Zend wrote in Hungarian in 1976 and translated into English (fig. 25). The temporally zigzagging narrative tells of a Toronto poet’s passionate and obsessive love affair with Nicolette, a woman half his age and the wife of a close friend, during visits to Paris and Florence. Not only is the chronology fractured, like a shifting, multi-layered dream, but also the chapters exploit a spectrum of forms and genres, playfully manifesting pieces of the story as haiku, Morse code, concrete poetry, a footnote, a play, epistolary narrative, Greek mythology, lyric poetry, censored text, and so forth. The novel also metafictively relates its own composition and birth: Nicolette from Nicolette.

Robert Zend was born in Budapest, the only child of Henrik and Stephanie. Most sources indicate that he was born on December 2, 1929. However, there is some uncertainty about the date. Henrik, the youngest among many brothers and sisters, married late in life, so that Robert’s cousins were ten to twenty years older than he.

Robert Zend was born in Budapest, the only child of Henrik and Stephanie. Most sources indicate that he was born on December 2, 1929. However, there is some uncertainty about the date. Henrik, the youngest among many brothers and sisters, married late in life, so that Robert’s cousins were ten to twenty years older than he. Zend describes himself during childhood as a social misfit as he wasn’t interested in playing sports with other boys. As a result of his introversion, Henrik and Stephanie suspected that their son was socially stunted as well as intellectually slow, and planned to take him out of school after the fourth grade to apprentice with a carpenter. However, Robert began to display talent in languages and to demonstrate more than a superficial interest in literature. When he was seven, he impressed his teacher and classmates with his language skills. At the age of eight, the precocious boy recited from memory a 140-line poem by nineteenth-century Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi.

Zend describes himself during childhood as a social misfit as he wasn’t interested in playing sports with other boys. As a result of his introversion, Henrik and Stephanie suspected that their son was socially stunted as well as intellectually slow, and planned to take him out of school after the fourth grade to apprentice with a carpenter. However, Robert began to display talent in languages and to demonstrate more than a superficial interest in literature. When he was seven, he impressed his teacher and classmates with his language skills. At the age of eight, the precocious boy recited from memory a 140-line poem by nineteenth-century Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi. However, the peace of those years was shattered with Hungary’s turbulent entrance into World War II. The years from 1944 to 1945 saw not only the Nazi takeover of Hungary and the deportation and murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews and others deemed undesirable by the regime, but also the Soviet invasion of Hungary (between October 1944 and February 1945) and its aftermath of rape, murder, and pillage. The Siege of Budapest by the Soviet military was one of the longest and bloodiest urban battles of World War II in Europe (fig. 4). The extraordinarily violent and chaotic transition from Nazi to Soviet control lasted about one hundred days and resulted in extremely degraded living conditions amid destruction, terror, disease, and starvation. Atrocities against civilians were committed by both Hungarian and Soviet forces. During the Siege, about 38,000 Hungarian civilians were killed. Thousands were executed outright by members of the Arrow Cross, the pro-Nazi Hungarian party.

However, the peace of those years was shattered with Hungary’s turbulent entrance into World War II. The years from 1944 to 1945 saw not only the Nazi takeover of Hungary and the deportation and murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews and others deemed undesirable by the regime, but also the Soviet invasion of Hungary (between October 1944 and February 1945) and its aftermath of rape, murder, and pillage. The Siege of Budapest by the Soviet military was one of the longest and bloodiest urban battles of World War II in Europe (fig. 4). The extraordinarily violent and chaotic transition from Nazi to Soviet control lasted about one hundred days and resulted in extremely degraded living conditions amid destruction, terror, disease, and starvation. Atrocities against civilians were committed by both Hungarian and Soviet forces. During the Siege, about 38,000 Hungarian civilians were killed. Thousands were executed outright by members of the Arrow Cross, the pro-Nazi Hungarian party. Tragically, Robert’s parents were among those killed during that brutal period.

Tragically, Robert’s parents were among those killed during that brutal period. For four years, from 1948 to 1951 (between the ages of 19 and 22), he worked for the Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, the state-controlled cinema during the Stalin regime, where he edited films, designed and produced dozens of movie posters, and wrote film reviews.

For four years, from 1948 to 1951 (between the ages of 19 and 22), he worked for the Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, the state-controlled cinema during the Stalin regime, where he edited films, designed and produced dozens of movie posters, and wrote film reviews. To earn sufficient income to help support himself, his wife, and in 1956 their newborn baby, he had to patch together a variety of short-term and part-time jobs. For four years, he worked as a free-lance journalist. In addition, he did writing and editorial work for children’s and youth magazines, edited books for the Young People’s Book Publisher, wrote reports and essays for a teacher’s magazine, wrote for the Hungarian Radio, translated poetry and essays from German, Italian, and Russian sources into Hungarian, and worked with illustrators, artists, and printing shops.

To earn sufficient income to help support himself, his wife, and in 1956 their newborn baby, he had to patch together a variety of short-term and part-time jobs. For four years, he worked as a free-lance journalist. In addition, he did writing and editorial work for children’s and youth magazines, edited books for the Young People’s Book Publisher, wrote reports and essays for a teacher’s magazine, wrote for the Hungarian Radio, translated poetry and essays from German, Italian, and Russian sources into Hungarian, and worked with illustrators, artists, and printing shops.

As a result of the massacre, widespread and violent protests erupted as outraged Hungarians witnessed the extent to which the Soviets were determined to maintain their grip on the satellite country.

As a result of the massacre, widespread and violent protests erupted as outraged Hungarians witnessed the extent to which the Soviets were determined to maintain their grip on the satellite country. By October 28, Hungarian fighters had suffered heavy losses but appeared to have been successful: the tanks withdrew from Budapest and the citizens enjoyed a few days of freedom from Soviet aggression. Ibi remembers the kettles that people placed on street corners to collect money for the widows and children of those killed in battle (fig. 11), and that there was a euphoric feeling of solidarity and mutual trust.

By October 28, Hungarian fighters had suffered heavy losses but appeared to have been successful: the tanks withdrew from Budapest and the citizens enjoyed a few days of freedom from Soviet aggression. Ibi remembers the kettles that people placed on street corners to collect money for the widows and children of those killed in battle (fig. 11), and that there was a euphoric feeling of solidarity and mutual trust. However, unbeknownst to Hungarian civilians, on November 3 Khrushchev approved Operation Whirlwind, a Soviet military invasion of Hungary involving sixty thousand soldiers. Early in the morning on Sunday, November 4, without warning, hundreds of tanks rolled into Budapest in a swift and brutal crackdown on the Hungarian Revolution (fig. 12), assisted by the AVO (Hungarian secret police). Many Hungarians actively resisted with guns and Molotov cocktails. It was an extremely perilous time: thousands of Hungarians were killed by superior Soviet power, and the dreaded AVO ruthlessly tortured their own compatriots whom they deemed to be enemies of the socialist state. The Soviet Minister of the Defense estimated that within three days the soldiers would have the city under control; in fact, the Hungarian insurgents kept fighting until November 11.

However, unbeknownst to Hungarian civilians, on November 3 Khrushchev approved Operation Whirlwind, a Soviet military invasion of Hungary involving sixty thousand soldiers. Early in the morning on Sunday, November 4, without warning, hundreds of tanks rolled into Budapest in a swift and brutal crackdown on the Hungarian Revolution (fig. 12), assisted by the AVO (Hungarian secret police). Many Hungarians actively resisted with guns and Molotov cocktails. It was an extremely perilous time: thousands of Hungarians were killed by superior Soviet power, and the dreaded AVO ruthlessly tortured their own compatriots whom they deemed to be enemies of the socialist state. The Soviet Minister of the Defense estimated that within three days the soldiers would have the city under control; in fact, the Hungarian insurgents kept fighting until November 11. For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and eight-month-old baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria. A close friend, István Radó, had created fake identification papers for the escape of twenty to thirty persons, and invited Robert and his family to join the group. Fig. 13 shows the card he forged for the Zends, certifying that their apartment had been destroyed, rendering them homeless, and authorizing travel.

For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and eight-month-old baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria. A close friend, István Radó, had created fake identification papers for the escape of twenty to thirty persons, and invited Robert and his family to join the group. Fig. 13 shows the card he forged for the Zends, certifying that their apartment had been destroyed, rendering them homeless, and authorizing travel. In the event they were stopped by Soviet soldiers, Robert and István had written a letter in Russian addressed to the soldiers (fig. 14), pleading with them to let them go on their way: “Dear Soviet Soldier, We are all ordinary Hungarian workers. Fathers, mothers, children, families, who lost everything—shelter and furniture, earned with hard labour. None of us fought against you. We are not fascists or partisans. We love you as you are also workers—providers for your families. We don’t like capitalists or imperialists. Our only wish is working in peace another twenty-thirty years. Our lives now are in your hands. If your hearts are opened up to love and you also love your family, you will help us and get our gratitude. We call on you, dear Soviet Soldier, help us! In the name of our children!!! Ordinary Hungarians”

In the event they were stopped by Soviet soldiers, Robert and István had written a letter in Russian addressed to the soldiers (fig. 14), pleading with them to let them go on their way: “Dear Soviet Soldier, We are all ordinary Hungarian workers. Fathers, mothers, children, families, who lost everything—shelter and furniture, earned with hard labour. None of us fought against you. We are not fascists or partisans. We love you as you are also workers—providers for your families. We don’t like capitalists or imperialists. Our only wish is working in peace another twenty-thirty years. Our lives now are in your hands. If your hearts are opened up to love and you also love your family, you will help us and get our gratitude. We call on you, dear Soviet Soldier, help us! In the name of our children!!! Ordinary Hungarians”

In Vienna, many voluntary agencies had quickly organized to provide relief for the refugees, such as the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the Lutheran World Federation, the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the World Council of Churches, and the International Rescue Committee.

In Vienna, many voluntary agencies had quickly organized to provide relief for the refugees, such as the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the Lutheran World Federation, the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the World Council of Churches, and the International Rescue Committee. At the Canadian Embassy, the Zends obtained visas to enter Canada (fig. 17). Before moving on, they stayed in Vienna for a few days, spending time with friends whom they knew they would not see for a long time, such as Skutai Ibolya, with whom Zend had worked at the children’s magazine Pajtás (Pal) in Budapest, and István Radó, who had organized the Zends’ escape and who was headed for the United States with his family (fig. 18). Zend would remain friends with Radó for the rest of his life, often flying from Toronto to visit him at his home in Los Angeles.