Camille Martin

A few months ago, I wrote a brief essay about Daymares, Robert Zend’s collection of stories, poems, and concrete poetry, one of his few books still in print. Zend (1929-1985) was a Hungarian-Canadian writer who immigrated to Canada in 1956, the year of the Hungarian Uprising. He settled in Toronto and worked for many years for the CBC. He was one of the most versatile Canadian writers, producing poetry, concrete poetry, novels, short fiction, essays, and plays. He was also a composer, a filmmaker, and a creator of mertz-like sculptures made of found objects.

While researching the Toronto Reference Library’s holdings of Zend’s works, I came across a thirty-year old treasure in the Special Art Room Stacks: Arbormundi (Tree of the World), a portfolio of seventeen of Zend’s concrete poems created on a typewriter, for which he coined the word “typescapes.” Although Zend didn’t invent typewriter art, he did seem to have created it without knowledge of any forebears in that genre. Below is the cover page. Following this brief essay are five more samples of typescapes from Arbormundi.

Zend’s typescapes are remarkable for their meticulous execution, which often involves superimposed shapes and figures. At the areas of intersection of these shapes, the effect is far from being muddied or heavy. Instead, they retain the delicacy that is characteristic of the whole.

Part of the beauty of these concrete poems is the ethereal effect produced by the transparency of the overlaid shapes. The result of this diaphonous quality is that it is difficult to determine which object is in front or behind the other: The objects seem to blend into one another, a visual legerdemain made possible by the open spaces of the typed letters and symbols: a superimposed “x” and “p” gives little hint as to which was typed over the other. Therefore the realm in which the ghostly forms interact spatially and symbolically is flattened into a plane of shared patterns and meanings. Zend’s often punning titles also reflect this idea of blending, as for example in “Peapoteacock,” where he brings “teapot” and “peacock” into verbal and visual contiguity so that one is contained within the other.

Another aspect of the beautiful intricacy of the overlaid objects is that the areas of intersection naturally produce darker areas, which form shapes of their own consisting of outlines of both objects (as overlapping circles in a Venn diagram produce a shaded area formed with arcs from both circles). The interplay of the shapes of each object with the shapes produced by their overlay creates an impression of both dialogue and unity between the objects.

The miracle of these concrete poems is that from what must have been a slow and painstaking process of planning and execution using paper inserted into a clunky machine come visions of airy lightness and delicate movement.

All of these effects harmonize with Zend’s recurrent themes of commonality and universality: the Other within the I, and the endless cycle of creation and destruction. They seem to be part of Zend’s spiritual expression of the continuities of life and death; as Zend puts it in Daymares, from the “prenatal . . . to the land of time-spacelessness; to the tiny centre point of our individual self which strangely coincides with the three-billion other human centre-points, with those of the dead ones, with those of our more ancient ancestors: swimming, crawling and flying creatures, rooting-stretching plants and perhaps even with the centre-points of other alien-living-units, of agitatedly swirling atoms and majestically rotating galaxies.”

Below are five typescapes from Arbormundi, which was published by blewointment press in 1982. A note to the portfolio states that “Zend creates them with a manual typewriter; no electronics, computers or glue involved.”

Following this sampling is a typescape by Zend based on a portrait of him by Hungarian artist Istvan Vigh.

Vivarbor (May 16, 1978)

Detail of Vivarbor

Orientopolis (Eastern city) (June 1, 1978)

Uriburus (April 13, 1978)

Rhumballion (May 14, 1978)

Peapoteacock (May 16, 1978)

Zendscape by Robert Zend, based on a portrait by Istvan Vigh

His boots are unlaced and he says, “You have to write this in fragments. Fuck a beginning. There’s no beginning. Fuck their middle—because there’s no middle, we’re in the middle; you can’t catch it while it’s happening. And fuck, fuck the ending because there won’t be an ending either. These are scenes. We come here to eat, to bullshit with you and a few other people. These are scenes. And you writing about Eddie and how he shot the moon out of the sky at five in the morning—that’s a scene that won’t mean shit to anyone but the person who saw it fall out of the sky, you know what I mean?”

Noetic cities

empty into assembly

line after

noons.

Swirl

sing sounds

index im

possibility.

A

symmetrical

words fade in

two hysterics

____________

The above poem attempts to undermine rational thought through a series of clever interactions between form and content. Such tactics are problematic, in that “cleverness is becoming stupidity,” and moreover, “clever people have always made it easy for barbarians, because they are so stupid*.”

Given this fact of cleverness, it may be of more interest to discuss an aesthetic concern unrelated to the above poem**. The EXPLANATORY NOTE for “Moonrise Paints a Lady’s Portrait” states that “poetry is the act of metamorphosing disparate images.” While certainly correct, this is but one aspect of poetry***. Poetry can also be thought of as sensation, or that which has “one fact turned toward the subject, and one fact turned toward the object. Or rather, it has no face at all, it is both things indissolubly . . . at one and the same time I becomes sensation and something happens through sensation, one through the other, one in the other (Deleuze, Francis Bacon 25).” Sensation, in other words, is the process of becoming faceless****; to this extent, sensation is not the subject nor the object, but the movement that takes place between the subject and the object: a transitive state: a verb that creates ephemeral and conditional nouns as effects of its action in highly specific contexts. Poetry, stated differently, is the movement of the subject (i.e. the poets as writers or readers) through and within the object (i.e. the text, whether materially, linguistically, or conceptually) that perpetually alters them both. As such, one may claim that “sensation is realized in the material,” while the material, concomitantly, “passes into sensation (Deleuze and Gauttari, What is Philosophy? 193).” If and when the movement ceases, both the subject and the object territorialize into rigid loci of the State; there is no longer poetry, but something else (e.g. stagnated nouns, information, communication, order words, commodities, exchangeable goods, etc.).

“While the poets agree that there is a certain amount of cleverness in the above poem, they do not necessarily agree with the EXPLANATORY NOTE’s assessment of cleverness, nor do they believe that it is the poem’s overriding concern.

**The poets do not believe that the aforementioned “aesthetic concern” is unrelated to the above poem. In fact, they are of the impression that it is very much related.

***Poetry, indeed, should be considered a multiplicity if one has any chance of understanding it, or better stated, moving comfortably through and within it.

****Foucault once wrote: “I am . . . not the only one who writes to have no face (Archaeology of Knowledge,19).”

Posted in concrete poetry, digital art, poetry, poetry magazine, Vispo, visual art

Tagged And/Or Magazine, Bunny Mazhari, Christophe Casamassima, Damian Ward Hey, Danielle Tunstall, Dawn Pendergast, Donna Kuhn, Joshua Ware, Kelley Irmen, Pale Fire, Vladimir Nabokov, William Gass, Willie Master's Lonesome Wife

Click here to see the whole paean to greed.

Camille Martin

Posted in concrete poetry, poetry, Vispo, visual art

Tagged Amanda Earl, Camille Martin, collage, consumerism, gimme, greed, National Poetry Month, ransom note collage, visual poetry

unarmed #60

unarmed is a gem of a zine with loyal fans in Minneapolis/St. Paul and beyond. It follows in the venerable footsteps of independent poetry zines of the 60s, often just mimeographed and stapled, such as Ted Berrigan’s C Magazine, Ed Sanders’ Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts, Anne Waldman and Waldman and Lewis Warsh’s Angel Hair Magazine, and a host of others since that explosion of small presses.

How many old school print poetry zines are still out there that haven’t converted to pixels? More than you might think, but not as many as before the advent of the internet.

unarmed makes reading poetry at the bus stop sexy.

Samples from unarmed:

Joel Dailey

Sheila Murphy

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

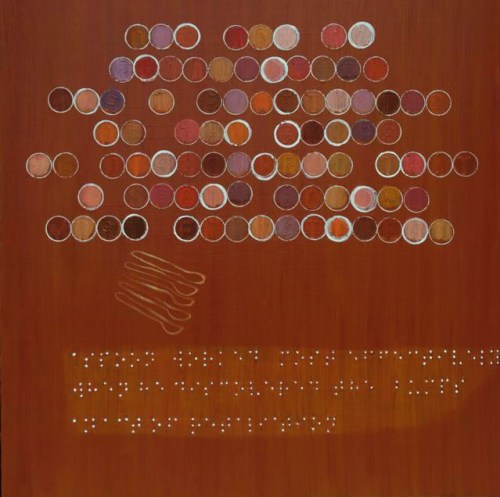

Gail Tarantino, One Act

In order to understand the interplay among the images in the three horizontal fields, it is necessary to decipher the Braille, something that I at first resisted. But my curiosity prevailed and I arranged the work on my screen next to a Braille alphabet and proceeded to decipher the sentence, letter by letter, yielding the following:

a spoon worked most effectively

when he discovered the bumps

an act of retaliation

As I progressed, the act of decoding it became easier, due to my increasing familiarity with the configuration of dots and the fact that after a few letters, guesswork came into play. A long word beginning with “effe . . .” can be guessed pretty accurately. But the slowness of my reading made me aware of how much take reading for granted, in a similar way that I take eating with a spoon for granted. Mulling over each letter in Braille slowed down the process. My brain, racing ahead of my slogging pace, was thinking of various possibilities, leading me to make incorrect assumptions a couple of times. I was taking too long to think about the text, so my mind was impatiently filling in the gaps in an effort to understand.

After deciphering the words, I realized that my effort was roughly analogous to a child learning to eat with a spoon: both are, as the title suggests, “one act.” This analogy is supported by the echoing of the shape of the Braille’s background colour, which is reminiscent of a spoon.

Tarantino compels viewers who do not know Braille to experience the unfamiliarity of the text and the opacity of its meaning until we decipher it, letter by letter. And in the act of doing so, we become conscious of the configurations of dots in each letter, recalling our original experience learning to read as a child, tracing the shape of each letter, as well as discovering the shape and usefulness of a spoon. Our reward is discovering something about writing as medium for communication, its thingy existence, as opposed to it being a system endowed with inherent meaning.

Significantly, the understanding of the Braille sentence is crucial to speculating on the meaning of the middle and top portions of the work. The middle portion consists of a series of spoons, one rather flat, like a knife, and the others in the familiar rounded concave shape.

The top half of One Act consists of scores of what look like little bowls. Some are missing, so that the pattern echoes the Braille in the bottom half. They are also different colours, resembling perhaps little pots of paint or perhaps bowls of soup, or food in the concave part of the spoon, the reward of the savvy child.

The question arises as to why Tarantino would describe the act of learning as on of retaliation, assuming that I am understanding the Braille sentence correctly. Retaliation requires first an act to retaliate against, so it seems plausible to assume that “he’ is retaliating against the opaque meaning of the spoon’s shape prior to his figuring it out, an opaqueness that strikes him as an act of hostility, which he counters by learning the usefulness of the spoon’s “bump.”

Carrying over the ideas in the message to the analogy of learning to read, the Braille sentence might suggest the concept of violence in the act of understanding. This idea is expressed in a set of conceptual metaphors in English, such as “to attack (or tackle, or surmount) the problem,” “to struggle with the meaning of something,” and “to fight ignorance.” These all suggest that understanding is a process of overcoming that which we don’t at first apprehend: the child “overcomes” the spoon’s unintelligibility; the uninitiated tackle the illegibility of Braille. And that violence is a retaliation against the violence of opacity, of being faced with something that is (at first) illegible.

Derrida’s theories on the violence of writing come to mind here, of writing regulating meaning, inscription as prohibition, law, circumscription. Before we deciphered the Braille, its meaning was opaque to us; it shunned our desire to understand it. Thus it might appear that Tarantino is turning the tables on the idea of violence inherent in writing, for the text (or the spoon) do their violence by remaining unintelligible, and the reader retaliates by learning and understanding. The violence of the reader is not the same as the violence of writing, for in Tarantino’s work, the reader’s violence is against illegibility. And meaning, interpretation, writing, and learning are not inherently acts of violence.

I may be overreaching in my musings here, and I certainly don’t mean to suggest that this is the only way of approaching this work. As One Act implies, there can be many different rewards to learning how to use a spoon, as the many bowls of soup in different colours attests, and by extension many different ways to understand a text.

In any case, I sense an acute intelligence at work in Tarantino’s work. It grapples with (to continue the conceptual metaphor) questions of representation, writing, legibility, and meaning in a condensed yet open-ended work. Did I mention that it’s also beautiful?

I highly recommend her website, where many of her works can be found:

Works consulted:

Derrida, Jacques. “The Violence of the Page.” Of Grammatology. Tr. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.

Marsh, Jack E. “Of Violence: The Force and Significance of Violence in the Early Derrida.” Philosophy and Social Criticism. 35.3 (2009): 269-286.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca