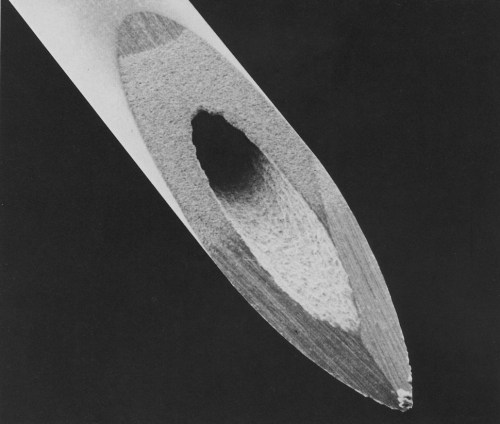

BEAN (photo: Camille Martin)

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Alberta Turner (1919-2003)

http://neglectorino.blogspot.com/

. . . which I just did: Alberta Turner. Her most recent publication, I believe, is a new and selected collection, Beginning with And (Bottom Dog Press, 1994). It’s available from Small Press Distribution.

Bottom Dog Press, 1994

Perhaps she’s less neglected a poet than I am assuming. Out of curiosity I searched the Poetics archives and found narry a mention of her (except for one post by me a couple of years ago). On that listserv, her death in 2003 didn’t register a tremor on the Richter scale. I also checked some long-standing and prominent poetry blogs of Poetics List members, and again, no mention. So I don’t think that she is particularly well known among the more experimentally inclined.

Thematically, she is a poet of the quotidian: she observes the minute moments of ordinary life and turns them inside-out to bring to light the contents of their pockets. She also knocks the icon of the domestic goddess off her pedestal.

In a sonnet entitled “Accounting,” a woman putters around the house, cooking in the kitchen, getting dressed, and tying her shoelaces that have come undone. All the while, she obsessively counts things in the kitchen and then her own multiple selves that seem to be reflected in a domestic hall of mirrors:

Accounting

Twenty of them. Count

five with heads

eight with holes

seven of some soft stuff—

You put boots on the cat,

a diamond bracelet on the crow.

Look at yourself grinning out of the spider web,

stuffing your twins into a pouch.

Two of you have identical spoons,

four go to the same shelf for salt,

three return to the fifth stone from the door

to tie your shoes.

A dried bee crunches underfoot.

Two of you will crunch bees.

Lid and Spoon (1977)

Her sardonic response to the tiresome, petty activities of daily life is evident in her reference to food she is preparing (“seven of some soft stuff”) and her self-mockery dressing before a cracked mirror (“stuffing your twins into a pouch”). She also inserts an element of absurdity and self-deprecation in her dressing, which is described in the language of the folk tale: “You put boots on the cat” (perhaps a reference to puss-in-boots, a children’s tale) and “a diamond bracelet on the crow” (“old crow” being derogatory slang for an unattractive woman).

Her counting exercise magnifies her sense of ennui performing repetitive mundane actions—holding a spoon, reaching for salt on a shelf, getting dressed before a cracked mirror, and hearing the crunch of stepping on dried insects. And her reference to herself in the second person reveals her alienation from herself. It is as though she were outside her body observing with subtle and good-humoured mockery her multiplied selves do chores.

Turner experienced the women’s movement of the 60s during her 40s; thus she spent the first twenty years of her adulthood in an overtly sexist society in which women were still by and large expected to function in traditional domestic roles. Turner, with sly humour, makes fun of her role, which she obviously doesn’t relish, of perfoming household duties.

Turner is not only a poet of domestic dissent. Her work, while largely accessible, is edgy and often disjunctive, qualities that threw off some critics, such as Margaret Gibson, who reviewed Lids and Spoons in the Library Journal in 1977. Gibson disparages Turner’s “astigmatic” vision in her “surreal collages” and “oracular riddles.” On the other hand, she praises Turner’s poems that form “organic wholes anchored in a world we can recognize for ourselves.” Critics who were accustomed to more accessible poetry were puzzled by her work’s experimental qualities such as odd juxtapositions, fragmentary phrases, and, as in the following poem, the unsettling use of nouns for verbs:

Mean, MEAN

Little eggs—blue, specked.

Laid, they grape;

feathered, they bead;

beaded, they

bird

very small birds

blur or brown, bellied

in white

What they mean is small:

beak-bite, spur prick,

brittle

spike.

*

I heard you,

MEAN!

Because hinge? Because tile’s hollow—

and straws and legs?

Because feet have the soles of feet?

Pockets for tails. A tail graft in

Capetown has held three weeks.

*

The soft part of conchs,

the stuff between shells.

I have bells of pods, necklaces of

teeth, but my tools

are spoon—somewhere a

pulp needs me—a drying juice,

an unhoused snail.

Learning to Count (1974)

The title, with its imperative to produce a more transparent meaning, could be a response to her critics who would tame the syntax and bridge the gaps. The first section begins quietly with a line designed, perhaps, to appeal to her critics. It is an image fairly bursting with preciosity: “Little eggs—blue, specked.” Then Turner slyly subverts the syntactical normalcy by splashing the parts of speech wherever she likes with quick, sure strokes: “Laid, they grape; / feathered, they bead; / beaded they bird.” Next follow three lines describing the “very small birds” in a tone similar to the first line.

She seems to turn to her critics to tell them what the poem means in case they missed it: “small.” The final three lines contain only six words, but they are so thick with alliteration, assonance, and near-rhymes that their meaning fades into the background and their sounds take precedence:

beak-bite, spur prick,

brittle

spike.

In their dense musicality, these short, energetic lines are reminiscent of troubadour poet Arnaut Daniel, particularly his chanson “L’aur amara,” which is also about birds, a favourite subject of Daniel:

L’aur amara

fa’ls bruels brancutz

clarzir,

que’l dous’espeis’ab fuelhs,

e’ls letz

becx

dels auzels ramencx

te babs e mutz,

pars

e non pars,

. . .

Even if you haven’t learned Medieval Occitan (and who has the time for it these days?), you can tell the extreme care with which Daniel selected each word to achieve a complex sonic weaving. *

In Turner’s three lines,

beak-bite, spur prick,

brittle

spike.

the “beak,” “spur,” and “spike” are tiny in relation to a bird’s body. But smallness is also expressed through the sounds of the words, which have a short, pecking quality to my ears, signifying the tiny motions of the bird’s beak, just as the sounds of Daniel’s lines might suggest the chirping of birds.

In the second section, Turner again seems to turn to her critics who would have her write more “meaningful” poetry, this time with extreme annoyance: “I heard you, / MEAN!” She then asks why she should mean, but her very questions belie her tendency to disjunction rather than “organic wholes”:

Because hinge? Because tile’s hollow—

and straws and legs?

Because feet have the soles of feet?

The last two lines are delightfully indecipherable. At this point, she is off the beaten track of clear meaning, talking in dry reportage style about “pockets,” “tails,” and a “tail graft in / Capetown.”

Turner has it her way in the third section, and this time, no critics are invited. The musicality of Turner’s range of tones and timbres is again reminiscent of Daniel:

The soft part of conchs,

the stuff between shells.

I have bells of pods, necklaces of

teeth, but my tools

are spoon—somewhere a

pulp needs me—a drying juice,

an unhoused snail.

In spite of its disjunctiveness (spoons and mollusks), the poem’s images echo impressionistically—although perhaps not in Gibson’s desired “organic unity.”

I’ll post one other poem by Alberta Turner, without comment:

HOOD BUTTON SHELL FUR

Gravity and wind so bells

feet in pairs ring pant legs

sausage curls clang hoods

domes hunch on traffic lights that lift

and swing

also cold its squirrel tail its nose drop

and cannon mouths their coin

*

One slave

to fasten the clasp of her cross

one

to slice her butter onto her toast

And she is fatherless

fed the bully to the meanest hog

sewed his buttons on a girl’s coat

*

Assume

that custard is smooth

that blue is sad and kind

Assume a god

ladle of fish

ladle of glue

And why not perch the snail shell on the log

as if the snail were still climbing out?

*

Three beans in a row red beans

three snows with no salt between

Ladder perhaps?

“Stop” And I would

But without wheels? Without road?

Stop an axe drop a hand

And fur is as angry as I can today

Lid and Spoon (1977)

* Ezra Pound, an admirer and translator of Daniel’s chansons, renders these lines as follows:

The bitter air

Strips panoply

From trees

Where softer winds set leaves,

And glad

Beaks

Now in breaks are coy,

Scarce peep the wee

Mates

And un-mates

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Rupert Loydell

Slow-Motion

Our baby swings slow-motion against the sky

chuckling as she comes towards us,

before reversing away still laughing.

I waited for a friend in the dark by the cathedral.

Life revolves around it, but no-one needs it any more;

we take for granted that meaning exists.

The sun swings slow-motion across the sky.

I push our baby, asleep in her buggy,

around the streets. Time passes so slow.

I have never known these suburbs so well:

the empty lawns, blank windows, tidied streets.

The days pile up, battered at both ends.

Doubt swings slow-motion across my life,

questioning how I spend my time,

muttering persistently about love.

With apologies to Loydell in case I miss the mark, I’d like to offer the following appreciation of his poem in an old-fashioned close reading.

Despite the cheerful opening image of a laughing baby on a swing, a sadness permeates Loydell’s poem due in part to the emphasis on the passage of time, exemplified by the motif of the slow-motion arc. The melancholic mood is also expressed in other motifs: the missed connections, the alienation of the speaker from his own existence, and the feelings of futility in the passage of time.

Failed or absent connections are the norm in the poem. The baby swings joyfully, but if hands connect with his body to push him, they are not evident. The speaker awaits a friend but doesn’t say whether or not the friend ever arrives. A feeling of oppressive ennui haunts the speaker’s stroll with the sleeping baby in the buggy. Instead of feeling comforted by his familiarity with the neighbourhood, he instead observes the clean orderliness of the suburban landscape with its “empty lawns,” “blank windows,” and absence of people.

Because of the speaker’s keen awareness of the present moment, time seems to pass slowly: the swinging arc of the baby and of the sun are depicted as is they were slow-motion film clips. Despite the unhurried pace of life, the days inexorably “pile up,” and the speaker feels less than satisfied with the meaning of his life, the days being “battered” both in the past and in the anticipated future. He knows that meaning exists, even though religion no longer provides the framework, but that meaning is subordinated to his feelings of separateness from others and anxiety about the trajectory of his life.

The personified doubt of the last stanza swings across the sky marking the passage of time and “muttering persistently about love.” Doubt appears as the mouthpiece of time, which accumulates the days in a futile pile.

In the second stanza, doubt’s skeptical turn of mind questions the necessity of God to give meaning to existence: “no-one needs [the cathedral] anymore.” Doubt might also cause us to take an ironic stance toward anything that smacks of certainty or sincerity. But here, doubt, instead of urging a cynical attitude towards love, instead seems to encourage a questioning of the things that humans do that lead to the absence of feelings of connectedness, of expressions of love. Doubt doesn’t loudly trumpet an imperative to connect, to bridge the gulf separating self from other and self from self. Instead, it “mutter[s] persistantly” like the speaker’s cranky conscience urging him to re-examine his life and to embrace human connection.

Loydell’s table-turning gesture to have doubt, not a more positive agent, muttering about love as though it were the underlying drone in the noise of life, is an apt stroke. Instead of encouraging us simply to fill the gaps in our lives with love, doubt urges us to question what it is that created the gaps in the first place.

Shearsman Books, 2004

Link to Loydell’s online magazine:

Stride Magazine

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in poetry

Tagged A Conference of Voices, Camille Martin, poetry, Rupert Loydell, Shearsman Books

And how’s that for burying the lead? Jensen’s poem hasn’t lost any of its appeal since I first read it about fifteen years ago.

“Bad Boats”

They are like women because they sway.

They are like men because they swagger.

They are like lions because they are king here.

They walk on the sea. The drifting

logs are good: they are taking their punishment.

But the bad boats are ready to be bad,

to overturn in water, to demolish the swagger

and the sway. They are bad boats

because they cannot wind their own rope

or guide themselves neatly close to the wharf.

In their egomania they are glad

for the burden of the storm the men are shirking

when they go for their coffee and yawn.

They are bad boats and they hate their anchors.

Laura Jensen, Bad Boats

The Ecco Press, 1977

Visit Laura Jensen’s blog:

http://spicedrawermouse.blogspot.com/

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in cognitive science, poetry

Tagged Bad Boats, Camille Martin, Clarence Laughlin, cognitive science, Laura Jensen, poetry

Rainbow Market Square Gallery (Toronto)

Sublime Scraps: The Collage Prints of Camille Martin

Ten of my collage prints will be exhibited.

80 Front Street East between Church and Jarvis

April 1 – April 30, 2010

Publication of Sonnets by Shearsman Books

Late 2009 or early 2010. Stay tuned for book launch information and tour dates. Sonnets will be distributed in Canada, the UK, and the US.

Shearsman Books Reading Series

UK Sonnets launch: early May 2010 (Click here)

Swedenborg Hall, Swedenborg House

20/21 Bloomsbury Way, London, England

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

http://www.eratiopostmodernpoetry.com/issue12_Martin.html

And speaking of sonnets in e.ratio, check out Nathan Thompson’s three:

http://www.eratiopostmodernpoetry.com/issue12_Thompson.html

It’s nice that Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino published the two sets of sonnets side-by-side, as I think there is an affinity between them, the reflexive slant in some of them, for one thing. Nathan tells me that his set of sonnets will be coming out as a chapbook with Skald (Zoe Skalding’s small press). I look forward to seeing this work, and not only because I’m on a sonnets jag.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in poetry

Tagged Camille Martin, e.ratio, Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino, nathan thompson, poetry, Skald, sonnet, Zoe Skalding

This little gem by Anselm Hollo is one of the most beautiful books, physically, in my collection. It’s a slim but perfect-bound book of 26 poems, of which only one spills onto a second page. The now-defunct Toothpaste Press used letterpress on fine paper and headed each poem with an ornate gold number.

The book’s title is one of those perfect puns, like bpNichol’s “Catching Frogs”: “jar din.”

In the poems of Heavy Jars, quiet, ordinary, even intimate moments are writ large, extrapolated into the universal human condition. Hollo’s subtle lyrics follow the cognitive path from moment to moment and often bubble with his signature twinkling humour. There’s a largeness of heart in these poems, which are also unabashedly musical, as in the first eight lines of “awkward spring”:

awkward spring

has spilled its

golden ink

all over the angels’ bibs

& off

the swan’s soft chest

white feathers fall

into the swamp

The short “i” sounds in the first stanza offer a delicate and ping-y quality, and the soft s’s, f’s, and “o” sounds give a contrasting luxuriant effect – both of which sounds suit the season.

Hollo also has an amazing ear for rhythm, as the above stanzas demonstrate as well as the lines “as the water goes / go / go / as the water goes.”

Heavy Jars contains two of my all-time favourite poems bar none: “awkward spring” and “big dog.” I’m also fond of the book because it contains this poignant inscription from Anselm: “Hard to say whether the jars’ve gotten lighter.” I like to think that he’s the first person ever to write “jars’ve.”

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in poetry

Tagged Anselm Hollo, bpNichol, Camille Martin, Heavy Jars, letterpress, musicality, poetry, Toothpaste Press

Posted in photography, poetry

Tagged Camille Martin, Lafayette Louisiana, New Orleans, photography, poetry, Rae Armantrout

Wires dip obligingly

between poles,

slightly askew

Any statement I issue,

if particular enough,

will prove

I was here.

There is something here that reminds me of Anselm Hollo, that quality of self-awareness, reflexivity, immediacy, the poem enacting its own claim, the poet conjuring her own DNA sequence in the particularity of the translation of perception into language. I remember years ago hearing Rae read in New York. I had only read her poetry on the page and didn’t really connect with it. But hearing her read was a revelation. The only way that I can describe it is that it sounded like waves of punchlines washing ashore, splashing over me. I felt exhilarated to connect with her work so suddenly and viscerally.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in digital art, poetry

Tagged Camille Martin, digital art, Peter Ciccariello, poetry, poetry reading, Rae Armantrout, Uncommon Vision, Versed

The third question of the false start: for poets who also practice some other kind of art, what is the relationship between the poetry and the other discipline? In the case of my poetry and collage, are the two in dialogue? I pondered this issue as I struggled to write a meaningful statement about my collages in preparation to contact galleries about a possible exhibition. I thought it relevant to mention my work as a poet, and found myself also making connections about my readings in cognitive science. Here is what I came up with:

* * * * * * *

Artist’s Statement: Camille Martin

I am both a collage artist and a poet. The two media are not mutually exclusive; they inform one another. My approaches to language and images are closely related: I gather materials (in the case of poetry, words or phrases; in the case of collages, backgrounds and cut-out images) and try different combinations until something larger than the juxtaposed elements emerges. After creating the collages, I digitally scan them and create enlarged archival prints on fine art paper mounted on white dibond.

The startling juxtaposition of images is key to my work. Lautreamont, a nineteenth-century writer, described beauty as “the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissection table.” That statement, which became a sort of anthem for surrealists, speaks to me of the mysterious charm that ensues from the dialogue among the images that I marry with scissors and glue. The images might start telling a narrative, or their meaning might remain mysterious and absurd.

One thing that we humans do best is to fill in the gaps of seemingly illogical juxtapositions: to “confabulate,” to tell stories in order to explain. Confronted with oddness, the mind rushes to fill the aporia between the unlike images, like water rushing to fill a depression in the earth: a snake levitates in the air, lifting with it a marble staircase; a mountain breaks apart to reveal to a climbing statue a secret city with buildings adorned with feathers; a broken puppet falls from the sky like Icarus; a naked mole rat watches enviously as two mating turtles fly across the night sky. The gaps that we fill with narratives are openings for the creation of our very selves, which is unending.

It is equally possible, confronted with the illogical, to allow the strange gaps to remain a mystery and to experience what the poet John Keats called “negative capability”: the capacity to allow the presence of uncertainties without trying to rationalize them, to allow “mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” The snake carries the staircase: that reality can exist in its own world, resistant to the attempt of any brain to reason with the oddness of it.

It’s important for me as an artist to allow both possibilities: interpretation and mystery; narrative and an irrationality that resists narrative. The interplay of these two possibilities constitutes for me the richness and playfulness of my work. There is magic and meaning—and poetry—in both states.

* * * * * * *

I recently sent a portfolio to the Women’s Art Resources Centre in Toronto in order to get a critique from a knowledgable artist and curator. I am still basking in her assessment, which was very positive in regards to the art (she writes that she is “impressed with the quality of the execution and the composition of the collage work” – woo-hoo!). Her main suggestion had to do with my artist’s statement: to situate my collages in a more contemporary context in order to place my work in the stream of a more recent tradition. Excellent advice.

Sage advice also from Snoopy, who responded to sourpuss Lucy’s refusal to dance the day away: “Four hundred years from now, who’ll know the difference?” That’s as good a response to Eliot’s weary despair as I’ve ever heard.

. . . . . .

I record here my website address, in what is probably a useless attempt to get Google to index it:

Camille Martin