After living for ten years in upstate New York, where I had never quite felt at home, I decided to return to my hometown of Lafayette, Louisiana, where flowers grew year round, people spoke in the soft, lilting accents of Cajun French, and I could eat crawfish étouffée to my heart’s content. No doubt there was a hefty dollop of romanticized nostalgia in my decision. In any case, I packed up my belongings and drove a big U-Haul south. Three days later, the humidity felt just about the right thickness, and I knew I was home. I took an apartment in Bayou Shadows, a sterile complex probably named by a focus group, and got a job as a secretary in a company that provided tools and labour for offshore oil rigs.

Over the next few months, I reacquainted myself with the local culture, attending celebrations like the Frog Festival in Rayne, the Cajun Music Festival in Mamou, and of course, Mardi Gras. I also visited Vermilionville, a recreated Cajun village on the banks of Bayou Vermilion showing life in Acadiana from settlement (1760s) to the late nineteenth century. It was recommended to me by my cousin, whose partner had a job demonstrating for the tourists the making of bousillage, a mixture of bayou mud and dried moss that the Cajuns used to plaster their walls. I felt a little sad to see the period costumes, Cajun-style homes and furniture, and farm tools, all authentically recreated and frozen in time.

When I was growing up, there were still some survivals of this old way, such as the “gar’ soleil” a practical bonnet that my grandmother wore to shade her face from the harsh sub-tropical sun, and the old plow pulled by mules that my grandfather was still using for his cornfields when I was a child. That way of life was gone, though you could still buy Cajun bonnets as a souvenir in the gift shop at Vermilionville. Seeing artifacts from the my culture ossified in a museum, I felt as though a part of my past were now being recaptured, tested for authenticity, and put on display. It was a lesson in impermanence that I was reluctant to learn.

While I was away in upstate New York, my father had immersed himself in genealogy. He and my mother collected hundreds of photographs and paintings of ancestors, and filled boxes upon boxes of documents photocopied from court records: marriage certificates, wills, contracts. They also collected and framed farm implements such as old cattle brands, correctly assigned to their owners. My father was becoming a kind of living Cajun icon, obsessively collecting the paper trail of his ancestors as a way of holding on to a culture that was swiftly dissipating as assimilation into the “mainstream” took its toll.

But nostalgia takes its toll on history, and the longing for a lost arcadian past tends to flatten the complex layers of history. What remains is an idealized mythology that takes the form of whatever fantasy nostalgia has invented. Perhaps it’s a vision of happy-go-lucky Cajuns whose unadulterated culture thrived in relative isolation from “les Américains.” Or perhaps it’s a fantasy of the good old antebellum days of oligarchy in the Deep South: wealthy plantations, elegant ballroom manners modeled after European nobility, and ultra-cheap labour. Whatever the fantasy, nostalgia creates a vision of life that used to be simple and pure, uncomplicated by the complexities of cultural hybridity and the inhumanity of slavery. This was another lesson that I was reluctant to learn. After all, I was in search of Cajun authenticity, and I was on the verge of buying into this vision of a lost culture innocent of divisions and contradictions; it was the misty, sunlit, and idealized vision of a lost childhood. Growing up during Jim Crow and witnessing the turmoil of the Civil Rights movement and the first attempts to integrate a society of institutionalized racism left an indelible mark on my psyche. But returning to Cajun country full of wistfulness, on some level I still clung to the belief, despite evidence to the contrary, that racism was not imprinted onto the Cajun social fabric.

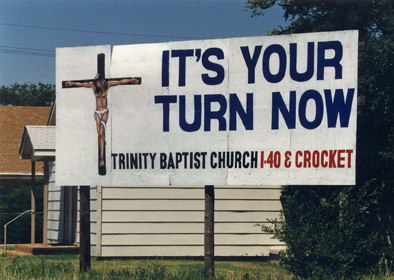

After my move home, I would sometimes drive in the countryside around Lafayette, with no particular destination in mind. I was looking for “authentic” Cajun life in the small towns where life wasn’t self-consciously re-enacted for the benefit of tourists, where life had not become a series of footnotes and framed antique tools. On one of those drives I found myself in St. Martinville, a town where many of the Acadians had first settled after arriving in Louisiana from Acadie, now Nova Scotia, in the 1760s.

I had been to St. Martinville several times as a child to visit the St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church. To me, it was the quintessential Cajun shrine: an historic eighteenth-century church built by the early Acadian settlers. Next to the church was a statue of a virgin—not Mary, but Evangeline, symbol of the Acadian diaspora.

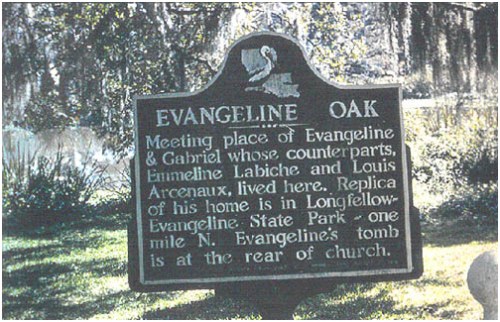

Evangeline was a character invented by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his long tragic poem based on the French Acadian expulsion by the British from Nova Scotia in 1755. Families were often split up as they were forced to hurriedly board ships during “Le Grand Dérangement,” and in Longfellow’s poem, during the loading of the Acadians onto the ships, Evangeline becomes separated from her betrothed, Gabriel. According to one version of the legend, on arriving in Louisiana years later, Evangeline discovers that Gabriel has already married another. After becoming mentally unhinged due to the shock, she dies of a broken heart and is buried under an ancient live oak tree in St. Martinville.

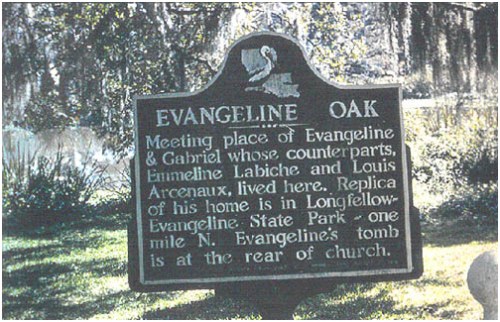

Even though she is an entirely fictional character, the tourism industry perpetuates the myth that she was based a real person (Emmeline Labiche, another fabricated character) and is actually buried under a live oak near St. Martin de Tours Church.

Layers of truth and myth are easily confounded where there is the desire to believe. Of course, there must have been many Evangelines and Gabriels, lovers separated during the expulsion of the Acadians, but none buried under the old oak tree at St. Martin de Tours.

I sat near the statue of Evangeline, which used to represent to me a fixture of the Cajun imaginary, an icon of the Cajun diaspora. The plaque at the base, translated into English, reads as follows:

* * * * *

Evangeline

Emmeline Labiche

Old Cemetery of St. Martin

In Memory of the Acadians Exiled in 1755

Statue of Evangeline, heroine of the Acadian deportation to Saint Martinsville in Louisiana.

* * * * *

Although there was no mention of a model, I remembered that the statue was in fact a replica of Delores Del Rio, the Mexican-American actress who played the lead role of Evangeline in the 1929 film.

Even Hollywood kitsch merges into the legend and takes on an aura of authenticity. Before the statue knelt two elderly Cajun women solemnly praying before the image of the tragic peasant maiden.

I walked inside the church, which contained the usual sentimentalized Catholic iconography as well as a simulation of piled-up stones surrounding a statue of Mary, a representation of the Grotto of Lourdes. The stones seemed more simulated than I had remembered as a child, but other than that, the church and grounds were pretty much the way I had known them. It was the kind of place I mentally file as a shrine that is still rooted in a living culture but that, once tourism grew into a serious commodity, became embellished with colourful folklore, complete with sacred landmarks and an empty grave. It seems that the more that fictional accoutrements spring up around a myth, the more credible the tale becomes. Even the locals wanted to believe.

Next to the church was a little museum. I entered the first floor gift shop and chatted with an affable middle-aged woman behind the counter about the interior of the church. She informed me that “It was a octoroon built the Grotto of Lourdes in the west nave. And do you know, he had never been to Lourdes before?”

Octoroon? It was bizarre to hear that antiquated word. Here we were, a good thirty plus years from the official end of Jim Crow, and this woman was still using, in all earnestness and without historical context, the long-outdated and legalistic term—common in the nineteenth century—for a person who was one-eight African-American. I felt transported to a different era. Or maybe a Flannery O’Connor story about the absurd underbelly of life in the rural Deep South.

She then pointed me in the direction of the museum exhibit upstairs, which she said I could see for one dollar. She seemed mysterious about the nature of the exhibit, only saying that “It’ll all explain it when you see it.”

Expecting an historical display about the church or the Cajun settlement in St. Martinville or some nonsense about the grave of Evangeline, I soon realized that I was about to enter one of those surreal zones—“geo-psychic wonders,” as a friend calls them—that you sometimes come across in South Louisiana. Like the little roadside chapel that I found on one of my countryside excursions, with stained glass windows depicting Houma Indians. Or the Saturn Bar in New Orleans, featuring a painting of the ringed planet on the ceiling along with a dangling mummy and a giant taxidermic turtle—for starters.

I climbed up the stairs to the museum on the second floor. The first clue was jagged strips of green camouflage cloth festooning the beam at the entrance. The mottled green fabric was crudely decorated with glitter in the shape of spider webs. As I crossed the threshold and walked into a single large room, something told me that this was not going to be a display created by the St. Martinville Historic Society. The entire room was bedizened with lurid, sparkling spiderwebs. Around the perimeter stood department store mannequins in stiff poses, dressed in gaudy eighteenth-century-style satin costumes of purple, green, and gold, the traditional colours of Mardi Gras. Plastic spiders perched on sequinned webs adorned the gowns.

A placard on the wall explained that these costumes were worn at a recent local Mardi Gras ball whose theme was an 1850 double wedding that took place on a nearby sugar plantation, the Oak and Pine Alley. According to this legend, apparently well-ensconced in the town’s lore, Charles Durand, the wealthy plantation owner and father of two young women engaged to be married, decided to throw the most lavish and memorable wedding anyone had ever seen. He imported spiders from China and set them loose among the live oak trees. On the day of the wedding, he had slaves spray gold and silver dust from bellows onto the spiderwebs, wet from dew, creating a glittering canopy for the ceremony.

The mannequins’ Mardi Gras ball gowns, a tribute to this wedding steeped in fantasy, seemed a bizarre conflation of Spider Woman, bordello madame, and Bo Peep debutante. At the far end of the room, a mantelpiece decorated in red felt with candelabras at either side served as an altar, complete with a male mannequin dressed in the colourful robes and sashes of a priest, ready to ward off errant spiders with his magic sceptre. In the middle of the room sat a dollhouse model of the plantation house and its oak grove, a kind of fuzz strung between the trees to depict the spiderwebs.

The unabashed campiness of the “museum exhibit” was hypnotic. Surrounding me were the symbolic fetishes of the legendary wedding—a cheesy fertility shrine in which images of spiders bring good fortune and Cajun rugrats to newlyweds. I lingered among the arachnophile mementos, imagining a future mutated version of the story: locals praying to spider spirits to grant favours, and dangling plastic spiders from their rear-view mirrors. Bridegrooms in Spiderman costumes at ritualistic weddings ravishing Miss Muffet brides. Evangeline would of course join the hagiography of the new syncretistic Catholicism. The sequel to her hallowed tale would tell of spiders interceding on her behalf to roll back the tragic diaspora and deliver her faithful lover Gabriel, whom she’d marry under the oak tree that now marks her tomb amidst showers of gold and silver glitter purchased from the local craft store.

After my reverie had played itself out, I thought about the woman downstairs, remembering her “octoroon” comment, and suddenly the invisible subtext of the exhibit came into focus. Previous experience told me that this latter-day celebration of plantations in the Deep South, whose owners had amassed huge fortunes from the labour of slaves, was nothing unusual. The at-best unthinking extolling of this dream wedding wasn’t only the result of seeing Gone with the Wind too many times or visiting plantations in which the tour guides attempted to rationalize slavery, minimize the suffering of the slaves, and glorify the expensive mahogany furniture and chandeliers in the roped-off rooms of the mansion.

Years earlier, I had toured the so-called San Francisco Plantation near New Orleans, open to the public for a fee. Women in large hooped skirts, evoking the stereotype of the Southern belle, served as tour guides. As the guide for my group showed us the kitchen, an outbuilding about a hundred feet from the mansion, she explained that a slave carried the prepared food from that structure along a stone path to the dining room. Especially when the slave was carrying a pie, she said, the master would require the slave to whistle so that he could be assured that the slave wasn’t eating the pie. I heard tittering among the all-white group of tourists. This was a geo-psychic wonder steeped in myth and mired in denial.

The racist backdrop of commemorations of plantation life such as the spider-wedding fades into invisibility, much like bringing up the suffering of the blacks during the plantation tours was taboo: it would have spoiled the fantasy. I looked back at the display of mannequins and diorama and felt both attracted to its absurdity and repelled by its sanitized history. This was home alright.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca