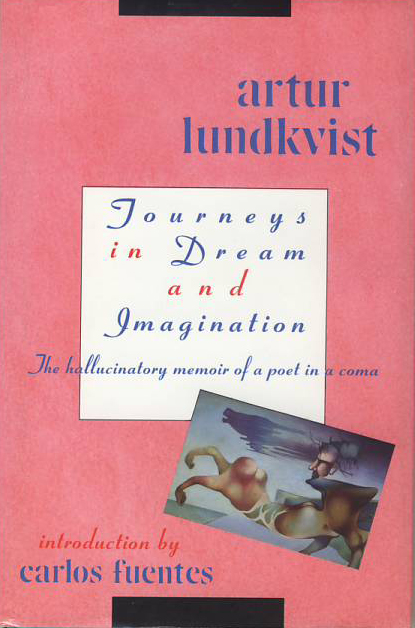

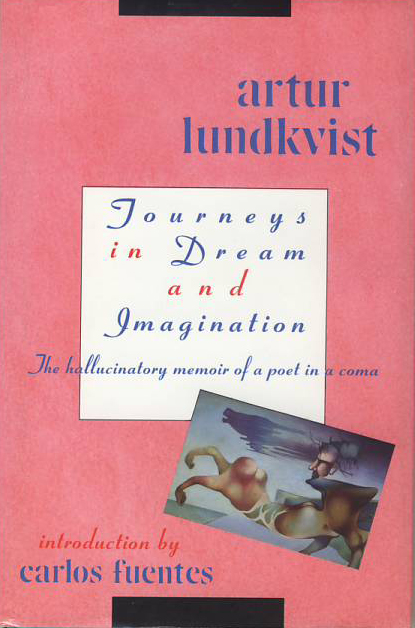

Excerpts from Artur Lundquist’s Journeys in Dream and Imagination (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1991),

Excerpts from Artur Lundquist’s Journeys in Dream and Imagination (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1991),

then a brief essay.

I know I am traveling all the time, possibly with no interruptions, also with no tremors or noises, soundlessly and softly, and then I am no longer lying in my bed but stepping out into the world where everything is awake, sundrenched, comforting, and I am there clearly as a visitor, and I am quite at ease,

it must be a dream journey I have undertaken, a definite dream journey where all is real precisely the way all journeys ought to be, but maybe one has to be dead in order to journey like that,

by the way, how can I know I am not dead, even though I have no sensation of being dead, and it is as if I rest in a middle zone without feeling either warmth or cold or hunger or any human needs

* * *

No wind, not even the slightest breeze, complete stillness and silence, yet I am traveling or have a definite sense of traveling, but how can it happen without a sound or feeling of movement,

can I travel motionless or glide onwards without the least resistance from the earth or the air, can it be that time has stopped or speed no longer has a meaning, that I have reached the crossroads beyond motion and stillness . . .

but yet I am here, can feel my body and sense my breathing, it is a nothingness that is definite, but without any wind or air or sound whatsoever, as if all but my own being has ceased existing,

it amazes me somewhat, but it actually does not matter, why should I need wind and sound, that which exists does exist nevertheless, and I must be the one perceiving it, and that is surely sufficient to make me alive and capable of perceiving,

I do not know what time has passed, but now I begin hearing something, at first vaguely, then with increasing strength, and soon, I can recognize a distant song by women, a choir like in a church but heard from a distance, the song rises and falls rhythmically, with different voices blending, lighter ones and darker ones,

It is actually not beautiful, but it still makes an impression by its inherent certainty and power, yes, the song bears witness of a conviction that conquers silence and nothingness as if journeying by its own force and conquering all resistance,

I feel that I am again traveling, that immobility and silence no longer reign, but I don not know what the women are singing or what the song means, it is simply there, filling the room which was only silence and emptiness

* * *

The silence is like a fine spiderweb against my face, I cannot rub it off, it is simply there without being tangibly real, it does not flutter like a leaf in the breeze, nor is it entirely immobile, it feels like the impression of a wind that is already becalmed, it is hardly the beginning of the weave and it does not betray a pattern, it is the most insignificant matter, yet it makes itself known

* * *

My dreams are of iron, so strong, so durable, but they soon begin to rust, eventually they fall off like flakes of rust and nothing is left of them, then I shift to dreams of dough so that I might bake and eat them, almost like bread,

suddenly, as I sit at the table in good company, I am nauseated, I do not even have time to stand up and run to the toilet before I spew out a snake that curls out of my mouth, one piece with each spasm, like a birth,

the snake lands in front of me, on the plate that is still empty, it is curled up, mottled, with a zigzag pattern on its back, more beautiful than a sausage and much longer,

the snake raises its head and opens its jaws as if to say something but at that moment, I faint and I do not hear it.

I’m attracted to unusual states of consciousness in the history of literature, such as Hanna Weiner’s poetic conversations with the words that she saw projected, involuntarily, onto surfaces; and those “Kubla Khan’s” written during drug-induced altered states of consciousness. One of the most remarkable poetic records of an altered state of mind is Artur Lundkvist’s

Journeys in Dream and Imagination: The hallucinatory memoir of a poet in a coma.

In 1981, at the age of 75, Swedish poet Artur Lundquist had a heart attack while giving a speech on Anthony Burgess. A friend administered artificial resuscitation and he was rushed to the hospital, where he lay in a coma in the intensive care unit for two months, his life sustained by a heart-lung machine. He gradually regained consciousness over the next few months, maintaining awareness for greater and greater periods of time. As soon as he was able to write again or at least to dictate to his wife, he attempted to re-capture the now-elusive dream visions that illuminated the two months of his coma as well as to set down the waking dreams that he experienced during the first year of his convalescence, intense and vivid ones in which his eyes remained open and during which reality mixed with unreality in a half-aware reverie. Such dreams are not uncommon for persons who have experienced a change in breathing patterns, as is the case being on a lung machine (1). Fortunately, Lundquist’s linguistic abilities were rusty but intact, and he was able to document his fantastical visions that arose during this fertile period of dreaming.

The memorable opening of his poetic journal of dreams, “I know I am traveling all the time,” suggests that he’s aware of his altered condition, and that the background noise of his mental state is his impression of traveling, paradoxically in “complete stillness and silence” and “without a sound or feeling of movement.” He exists “without distance in time and space” yet he feels that he is traveling “through time or space.” He can’t tell if he’s “lying in the same place” or “traveling without interruption.” He’s unaware of minutes and hours passing, “yet time is moving somehow.” It’s as though he existed in suspended animation while riding a train. He describes his state of mind during his convalescence as being full of contradictions: moving yet stationary, timeless yet in time, lonely yet also belonging, unaware yet on some level conscious. In this twilight state, while he’s on life support in the hospital, he dreams, sometimes about his own death and sometimes about the annihilation of the earth. Fantasies of nothingness, purposelessness, and oblivion haunt him in his awareness that his own consciousness could easily fritter away and end rather than be revived, and that eventually nothing will be left of the earth and all its life forms: “nothing that can see or feel or think remains in existence.”

His journey is metaphorical as well as viscerally sensed. The point of departure of the journey is a state of suspension in a world of silence and paralysis, as if he were in a cocoon. He seems to be neither conscious nor unconscious, and sometimes, for brief periods, he perceives the objects and people in his hospital room, but he’s helpless to make contact with them. The journey is one of transformation, and his destination is consciousness, the regained ability to speak and read, and ultimately, the ability to write about the journey of his dreams.

Yet he has no sense of destination in his dream journeys. What he has lost—his consciousness of place, of his body in a particular space, situatedness—becomes an obsession in his dreams. In a particularly poetic entry that is reminiscent of Stephen Dedalus’ meditation on place, telescoping from self to universe (2), Lundquist describes a village of farms in some detail, then zooms away:

behind that the forest began, and the moors, the meandering creek and the half-overgrown lake, the cows who grazed without fences, knew the paths and followed them, and returned when it was milking time,

then there was the church village and the whole parish, the district and the county and the whole country, and it was on earth in the universe, below the sun, the moon, and the stars, with years carved into tree trunks without revealing if the world was actually old or still young

Like Dedalus’ list, Lundquist’s image of an ever-expanding view tells of his wished-for certainty of place in an orderly world in which you know exactly where you are, even though there is a mystery about where you’re precisely bookmarked in the age of the world. When he does feel, in his dreams, a strong sense of self, that self feels alien to him: he doesn’t recognize the echo of his own shouting voice. It is absence and loss that most often shape his dreams, as when he envisions a couple buried alive after a strong earthquake, or a living, sentient stone mountain that is being cruelly and terrifyingly quarried by men who are more murderers than miners, or himself as the village idiot, “carry[ing] within [him] something that has never fully blossomed.” He’s in purgatory, a guest lost in a vast hotel, a village hidden in a mist. Corporeality and consciousness are absent or impaired, and desire—for life, for sexuality, for communication—is thwarted since the means necessary to fulfilling these desires are in a liminal state, halfway between action and immobility and unable even to know with certainty whether he is alive or dead.

Journeys in Dream and Imagination is a record of meta-dreams, meditations on Lundquist’s state of consciousness, dreams about the dream state. In the beginning of his journey, his dreams are “of iron, so strong, so durable.” However, this strong state of consciousness gradually starts “to rust,” and the dreams “fall off like flakes of rust” until they vanish entirely. He then switches “to dreams of dough,” which he bakes and eats, “almost like bread” that nourishes him through this period of amorphous half-consciousness. The metaphor of the consumption of dreams describes the interiority of his state of mind, and the next image of vomiting a snake that is also a giving birth to speech seems to signify his ability or desire to engage once more in communication with the world outside his twilight prison. Within his dream state, he sometimes interprets the vision he has just experienced, as when he sees trees growing between his toes and believes that dream to be a good omen, a “sign that life continues to grow inside me.” It is as though his consciousness were trying to solve the puzzle of its own impairment.

The necessarily interior turn during this period when perception of the outer world was subdued or shut off perhaps accounts for his awareness of his body, which he felt to be in a state of flux (the sensation of traveling, for example) and transformation: he has become something of a shapeshifter. In two successive dreams, he is transformed into a giant and then a miniature person, in the manner of Gulliver’s Travels. Proprioception is the brain’s ability to locate the position of the body relative to its own parts as well as to the exterior world. Since altered states of consciousness (during meditation or praying, for example) can change the strength of a person’s feeling of separation from or continuity with exterior space, other people, or objects, I wonder whether Lundquist’s dreams reflect disturbances in his proprioceptive sense of self in relation to others. During his convalescence, his brain was repairing itself—but was it also rehearsing, in a sense, the process of its own repair? Is this what the image of consuming the nourishing bread of his dreams signifies? If reinforcing the lessons of the day in a kind of rehearsal of knowledge is part of the function of dreams, as some neuroscientists studying sleep now believe, what was the purpose of Lundquist’s dreams, if indeed they can be said to have one? Why do so many of them have the feel of meta-dreams about the journey towards consciousness?

Regardless of the purpose of these dreams, it seems likely that Lundquist’s hallucinatory visions, alternately peaceful and nightmarish, represent his fears of being forever in a coma and his hopes of someday rejoining the realm of real people, objects, places. In his dreams, he creates worlds of uncertainty, where nothing can be pinned down as completely familiar and habitual; where communication is problematic or impossible, consciousness is present in some way but still suspended in a timeless, placeless journey; and where he is alien to himself and inhabits a world that is strange and unrecognizable.

His limbo is real and extreme, but there is something oddly familiar about his dilemma dramatized or described in his dreams, something that elicits the feeling that you’ve been there, too, in moments of doubt or frustration, when order dissolves, when thought fails to render its shiny nugget, when self seems irremediably scattered, when you feel alone on a teeming planet that seems to belong to another dimension, when talking to others falters and stumbles, when you no longer know who or why you are, and the world, faced ultimately with demise, seems pointless but stubbornly present. In his meta-dream stories investigating suspended being, the often surreal analogies for these states are almost endlessly inventive. But in them one can also read a description of what it is to be human, or to exist in “negative capability,” as Keats called the ability to live with “uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.”

Part of the pleasure of Lundquist’s record is becoming aware that even in a coma, the mind can cut seemingly endless facets in which to reflect itself and rehearse the dramas—miniscule or vast—of its journey through the interior. If his world seemed to be a solipsistic nightmare from which he couldn’t completely awaken, he peopled that world with rich possibilities and a self-awareness that sometimes comes across as more lucid and knowing—for all its twilight uncertainties—than the consciousness he so desperately wanted back.

(1) I gleaned most of the information in this narrative of Lundquist’s heart attack and recuperation from Carlos Fuentes’ introduction to the book.

(2) He turned to the flyleaf of the geography and read what he had written there: himself, his name and where he was.

Stephen Dedalus

Class of Elements

Clongowes Wood College

Sallins

Country Kildare

Ireland

Europe

The World

The Universe

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Joan Retallack’s Little Universes

The Little Universe of Infinite Time

Who can say which of all possible things should happen

next. Many were more or less content as many others ran

shrieking out of houses. Many many ran to hide in forests,

mountains, deserts. Many many many ran toward what

seemed to be safety zones between houses, in mountain

crevasses, across closely guarded borders, in desert mirages

and magical clearings in dark woods. Many more were

unlucky and couldn’t get away. The panel poured clear

water into clean glasses and cleared throats. The theys who

survived couldn’t talk about it themselves because of the

nature of impersonal pronouns. It’s said they took to

looking for meaning among frequently misspelled words.

Of course hope springs eternal in the little universe of

infinite time.

The Little Universe of Ten Minutes

Standing at the far edge of another unsettling interruption,

barely visible, not at all audible. Waving, smiling, pelted by

beams of electrons, photons, and other elementary detritus

streaming out of the inception of this perfectly calibrated

world. Hands thoroughly washed, synaptic pruning all

done. Want only to establish the time of the tragic event. It

was five in the afternoon it was exactly 9:30 am it was

eleven o’clock plus or minus twelve hours. She said come

back next week. I’ll tell you the answer. She had said come

back next week. We hesitate to mention it, but next week

had already happened in the little universe of ten minutes.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Share this:

Leave a comment

Posted in poetry, poetry magazine

Tagged American Letters & Commentary, Joan Retallack, The Bosch Notebooks