(photo: Camille Martin)

(photo: Camille Martin)

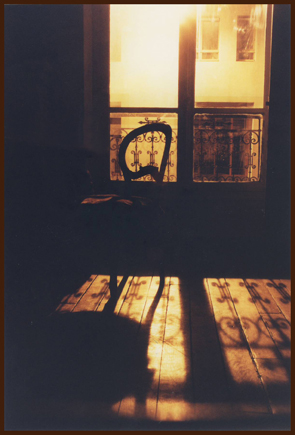

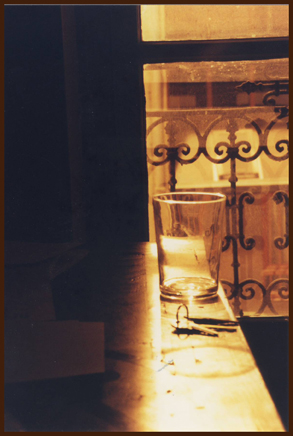

Another time warp in my Louisiana series: a St. Joseph’s Altar created in 2003 on the front porch of a house in Carrollton, the New Orleans neighbourhood where I used to live. The tradition of creating and decorating altars devoted to St. Joseph every year on March 19 was brought to New Orleans by Sicilians and adopted by some African-American devotees of the popular saint in the Catholic pantheon.

Non-meat food offerings embellish the altars and are usually given to the poor at the end of the celebration. Bread offerings are often baked into shapes of carpenters’ tools such as ladders or saws, but this altar keeps it simple and efficient with a loaf of Sunbeam bread. The beads of moisture condensed inside the plastic bag are a typical phenomenon in subtropical New Orleans, which can be warm and muggy even in mid-March.

During the day, people knelt at the altar and prayed. In the second picture, the woman might appear to be reverently bowing her head, but she was actually dismantling the altar at the end of the day: many of the food offerings have been removed, but the rows of candles remain.

The adoption of Sicilian traditions by African Americans in New Orleans is not an unusual type of cultural phenomenon: the blurring of cultural and religious boundaries is the rule rather than the exception in southern Louisiana, which has historically attracted settlers from all over the world looking for opportunities in spite of the prevalence of diseases and natural disasters, and forcibly brought people from Africa as slaves. For many, survival meant mutual aid within their ethnic communities and interdependence among their diverse neighbours.

Louisiana’s “cultural gumbo” is not a cliché for nothing. Louisiana, especially along the Mississippi Delta, was—and is—a mixture of Spanish, French, African-American, Irish, Italian, Native American, Croatian, Cajun, Creole, German, Czech, Hungarian, British, Isleño (from the Canary Islands), Filipino, Mexican, Cuban, Guatemalan, Chinese, Vietnamese, Laotian, Thai, and more.

As a result of intermingling among ethnic and national groups in Louisiana, Germans along the Côte des Allemands, for example, became more French, translating their names from Zweig to Labranche, and from Troxler to Trosclair. Many of the original Louisiana Germans came from the Alsace region, which partly accounts for the ease with which they shared customs with Louisiana’s French. Some Louisiana Germans have become so distanced over time from their origins that they believe their ancestry to be Cajun or French Creole.

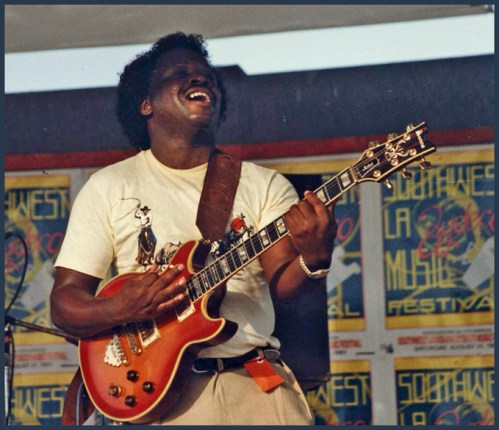

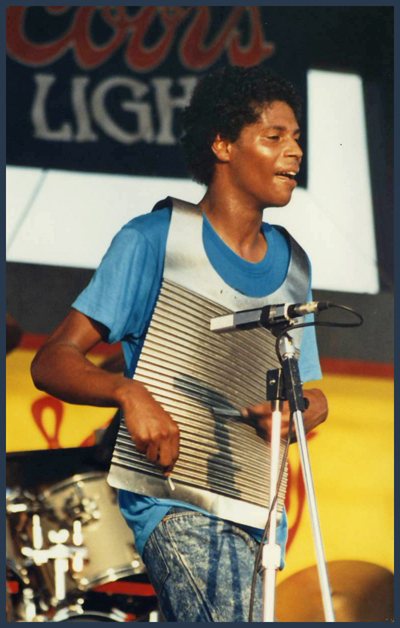

African-Americans intermingled and intermarried with French Creoles, Cajuns, Italians, and Native Americans, among others, and survivals of these blends among blacks can be seen in the French Creole language, St. Joseph’s Day altars, Zydeco music, and the customs of the Mardi Gras Indians.

It would be hard to find a group not influenced by black African and Caribbean culture in Louisiana. And the whole world, late in the twentieth century, tried to become Cajun by eating crawfish and dancing to Beausoleil.

Some groups in Louisiana seem to have had more permeable boundaries than others. Croatians, many of whom developed the oyster industry, created relatively close-knit communities with a tendency to preserve their own cultural heritage and not to mingle their customs with those of other groups.

And generally speaking, in the early settlement of North America, French colonists were more likely than British to intermingle their customs and blood with other groups. When I was researching Acadian culture in Nova Scotia, I discovered the extent to which the Acadians and the Mi’kmaqs, for example, had developed a close and interdependent relationship. One manifestation of the friendship between the two groups was of course their not-infrequent intermarriage. Another striking example of the degree to which both groups let down their boundaries was the syncretistic nature of a spring celebration that evolved: the return of the geese came to be celebrated in a hybrid feast blending Easter rituals with the Mi’kmaq Festival of Dreams and Riddles. I can imagine the consternation of the priests.

From the beginning of their settlement in Louisiana, the Cajuns continued to synthesize the customs that they brought from Acadia with the customs they found in their adopted land. A study of Cajun music, for example, shows influences from hillbilly music, blues, and Texas swing. If the Cajuns were viewed by the rest of the United States as unique and isolated, it was only by comparison with that amorphous category called the “mainstream.”

Throughout much of the first half of the twentieth century, the United States government instituted a policy of assimilation of the Cajuns in Louisiana, and until the late 1960s, many aspects of their culture were finally succumbing to decades of this unenlightened approach. Without a boost from the schools, the French language in Louisiana would probably soon have died out, for mine was the first generation of Cajuns, generally speaking, whose first language wasn’t French and who were increasingly unable to speak in the mother tongue of their parents and grandparents. With the advent of CODOFIL (Council for the Development of French in Louisiana), a more enlightened view of Cajun culture and heritage has permeated the curricula of primary and secondary schools of Acadiana, where Francophone teachers from France and Quebec have been hired to teach children the language of their parents.

Ironically, the movement for the preservation of the Cajun heritage threatened to turn a living culture into ossified museum artifacts. Cajun historical villages such as Vermillionville and Acadian Village recreated for visitors “typical” life in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Cajun communities, and people flocked to south Louisiana to experience “authentic” Cajun culture. Some forms of historical reflection, however informed or uninformed or misinformed, however laden with stereotypes or invested in historical accuracy, can contribute to the dying of a culture if there is an impetus to petrify it into some notion of its past–especially a past purified of other influences–instead of allowing it to grow, breath, change, and, most importantly, transform and renew itself from contact with other cultures.

One of the consequences of the policy of assimilation was an overall feeling of inferiority on the part of the Cajun people, a conviction that their culture was backwards and their French language less correct that that of their distant Parisian cousins. But pride is not without its pitfalls—pride in some notion of Cajun-ness, of a Cajun purity that never was and never will be. From the moment that the Acadians set foot on the shores of what is now Nova Scotia, they were influenced by the Mi’kmaqs and by the British, with whom they traded and fought. From the time that they settled along the bayous and swamps of the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana, they gathered still more influences in their vocabulary, food, customs, stories. Like any migrating group, they brought with and they borrowed from. Purity is an attitude that bears no resemblance to the infinitely re-folded layers of human culture.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca