The Haussmannian Revolution

A 45-million-year-old prelude

Ever since Romans in conquered Lutetia practiced open-pit mining to extract “Lutetian limestone” for their grand municipal projects, Paris has quarried the stone for its warm-toned buildings. And because limestone is a sedimentary rock composed of ancient marine life forms, Paris’ building block of choice actually consists of tiny fossilized mollusk skeletons.

This 45-million-year-old dimension of Paris adds an extra-ancient layer of history to a city whose architecture spans two millennia, from Roman to ultra-contemporary. Plus its greyish-cream stone gives Haussmannian Paris its characteristic warm ambience.

Below: Shelly fossils in a limestone building, appropriately enough next to a “History of Paris” placard.

Some earth science teachers take their students on scavenger hunts in the heart of Paris to find fossils on the surface of limestone buildings.

Haussmannian streets of the Second Empire: uniformity and discipline

From 1852 to 1869, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, with the blessing of Emperor Napoleon III, transformed the urban landscape of Paris from narrow, winding medieval streets into a network outlined by broad boulevards interconnected by etoiles, or stars with roundabouts. The challenge was all the greater as the city’s population had doubled in size with the annexation of suburbs.

Haussmann’s streets in the new plan were lined with uniform facades of residences grand and modest, commercial spaces, and churches, and they were punctuated by monumental structures such as triumphal arches, large churches, and government buildings. A new infrastructure for water, gas lighting, sewerage was created. Parks were distributed with the idea of providing all districts and neighbourhoods with recreational spaces. And the all-important trees were planted along the streets.

Imagine living in Paris during the second half of the 19th century and enduring decades of dust, rubble, and major disruptions to life. As exciting as the Haussmannian project was to many Parisians, weariness eventually set in.

The keyword in early Haussmannian Paris is uniformity, aesthetically and formally,. Haussmann conceived of a block as a uniform set of facades, strictly regulated by building requirements for the height of storeys, balconies, and windows. The Third Empire saw a relaxing of such architectural regulations, but meanwhile . . .

Des pins, des pins, des pins . . .

An acquaintance whose family owns a pine plantation in the Southwest of France commented on the monotony of the acres and acres of pine trees: “Des pins, des pins, des pins . . .”

I think of her words when I’m faced with a seemingly endless succession of Haussmannian buildings, especially those constructed early in the urban revolution when architectural homogeneity ruled. The height of the stories were required to be uniform, and windows and balconies lined up with military precision, creating strong horizontal lines on the facades, unbroken across a block.

Rue de Rivoli, the first street to receive the full Haussmannian treatment:

Iconic Haussmannian blocks, appropriately enough on Boulevard Haussmann:

Boulevard Maleherbes:

If Haussmannian uniformity can at times be “distressing,” the prospect below might quality.

The Grand Boulevard in a Trench

The sunken Boulevard St-Martin, with its raised, wide pedestrian sidewalks, is one of my favourite streets in Paris. One literally walks above the traffic along a spacious sidewalk, somewhat removed from the noise of engines below.

Before Boulevard St-Martin was a boulevard, it was a bastion, a stronghold on a hill that was part of Charles V’s city wall, which lasted from the 14th to 17th centuries. The Wall of Charles V became the route for Haussmann’s grands boulevards, which form a large semi-circle around the Right Bank. The portion that is Boulevard St-Martin was dug into the bastion-hill, while the sidewalks remained about two meters higher.

Haussmann’s grands boulevards attracted the entertainment industry, including some of the earliest motion picture theatres such as the cinématographe of the Lumière brothers. Boulevard St-Martin shares in that heritage. Below is Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, an institution that began as the Paris Opera in 1781. The current building was constructed 1873 and to this day functions as a theatre and opera house.

Lending his name to this tradition on the grands boulevards, pioneering silent filmmaker George Méliès was born in a residence on Boulevard St-Martin. Famous for Voyage to the Moon, Méliès created many fantastical early silent films.

Aside: If you haven’t seen Martin Scorsese’s magical film Hugo, which weaves a fictional narrative around the rediscovery of Méliès and his films, I can highly recommend it.

Architects of L’École des Beaux-Arts

Haussmann’s grand rebuilding of Paris spawned a new generation of architects, who by and large were educated in the conservative École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) and inspired by the ancient architecture of Greece and Rome. Below are some architects who rose to prominence, before and during the Second Empire.

Henri Labrouste’s university library

A prominent example of pre-Haussmann architecture that arose from École des Beaux-Arts is the main library of the University of Paris:

While the exterior is regular and rather conservative, the interior reading room of the library is more adventurous, with exposed cast-iron arches on the ceiling (an early use of iron in combination with stone and glass).

Victor Baltard’s Iron and Glass Innovations

Église St-Augustin

Église St-Augustin (completed 1868), at the northern end of Boulevard Malesherbes, is a marriage of iron and stone designed by Victor Baltard, one of Haussmann’s favoured architects. The enormous dome was possible due to Baltard’s use of a supporting iron frame.

Eclectic in style, St-Augustin has been described variously as Tuscan Gothic, Romanesque, and Byzantine.

St-Augustin, at the northern end of Boulevard Malesherbes, exemplifies Haussmann’s strategy of placing an architectural monument at the end of a grand boulevard to provide an imposing vista.

Covered market pavillions of Les Halles (destroyed)

Baltard designed a huge complex of iron-and-glass pavilions (1853-1870) for Les Halles, the historic market of Paris. The 1971 destruction of Baltard’s pavilions is a familiar lament in discussions of Paris’ great architectural losses. One pavilion from the huge complex was preserved and moved to a location in Nogent-sur-Marne, an eastern suburb of Paris — so Parisians can experience a bit of what they lost. And one pavilion was moved to Japan.

Marché Saint-Quentin (in the style of Baltard)

But at least one covered market from the Napoleon III period survived the wrecking ball: the 1866 Marché Saint-Quentin on Rue Magenta. I’m not sure who the architect is, but this covered market echoes the style of Baltard’s famous marketplace and in fact was built at the same time. The iron framing supports the glass, which allows natural illumination of the covered market’s interior.

Charles Garnier

Architect Charles Garnier (of Palais Garnier fame) flourished during the reign of Napoléon III. Garnier’s style, sometimes described as Neo-Baroque, puzzled people during his own time. Garnier himself dubbed the style “Napoleon III.” In any case, his approach to architecture arose from the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied.

Garnier designed an edifice for the Le Cercle de la Librairie, an association of professionals in the book industries:

The Third Republic: fin-de-siècle architectural laboratory

As the fin-de-siècle approached, building regulations in Paris requiring conformity were relaxed. Architects increasingly incorporated metal, glass, and polychrome structures into the more traditional limestone architecture of the earlier Haussmannian period, giving rise to a proliferation of hybrid styles.

Printemps Haussmann — nascent Art Nouveau

When the 1865 department store Printemps Haussmann burned in 1881, Paul Sédille designed and completed its reconstruction during the 1880s. Metal was becoming increasingly important as a building material (think of the contemporaneously constructed Eiffel Tower). Sédille used metal as a decorative as well as structural element of the new Printemps,

Also, Sedille’s interest in architectural polychromy, influenced by visits to Spain, is evident in his commissioning of colourful Venetian glazed terracotta mosaics for the store’s name emblazoning the towers.

The age of the international exposition

From 1855 until 1900, Paris hosted five international expositions. Inspired by London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 and its architecturally revolutionary Crystal Palace, Emperor Napoleon III, not to be outdone, responded with the Paris Exposition of 1855 and its even more impressive Palais de l’Industrie. That structure no longer exists, but thus began an era of glass and steel palaces and of the increasing use of these materials in innovative ways.

No substantial structure exists from the earlier expos, but the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle produced the Tour Eiffel. More about this monument in my next post on Art Nouveau.

The 1900 Paris Exposition occasioned the building of structures intended to be more permanent: a glass palace and smaller palace, an ornate and monumental bridge, and two great train stations. Among other things, the exposition showcased technological innovations and the Art Nouveau style.

The surviving structures created for the 1900 Paris Expo deserve their own post: Le Grand Palais, Le Petit Palais, Pont Alexandre III, Gare de Lyon (rebuilt for 1900 Expo), Gare d’Orsay (now the famous museum specializing in Impressionism). Below, just a few highlights.

Le Grand Palais, the glass palace built for the 1900 Paris expo, celebrates the architecture that was perfecting the art of the glass and steel monuments and showcasing Art Nouveau decoration inside the large exhibition space.

Below: One of Petit Palais’ famous murals, this one on the Dutuit cupola. The work by Maurice Denice narrates the history of French art. Below it, a wrought iron grand staircase flows like a weightless spiral of black Art Nouveau lace.

Pont Alexandre III

The ornate, monumental bridge Pont Alexandre III connected pavilions at Expo sites on the Left and Right Banks.

The monumental ceramic entrance gateway below, created by the Sèvres manufactory, decorated the facade of the Palais des Manufactures Nationales. It was salvaged from the destroyed building and now decorates Square Félix Desruelles.

Two great train stations: Gare de Lyon & Gare d’Orsay

Before leaving Paris Expo 1900, a brief visit to one of two train stations completed for the event: Gare de Lyon. The exteriors of these train stations, like so many built around the same general period, echo the form and movement of locomotives. Gare de Lyon even looks a bit like a locomotive. The rhythmic arched windows evoke the wheels and the circular motion of the pistons, as well as the repetition and motion associated with train travel.

What a gift to Paris and the world at large that the former Gare d’Orsay was preserved and converted into a great museum. The ceiling of the entrance gallery is a great glass awning, cousin to the glass palace.

Notre Dame du Travail

This church was built to accommodate the growing population of workers hired to construct the buildings of Paris Universal Exposition 1900. The unassuming exterior gives no clue as to what’s inside.

The exposed metal beams and support structure give the church a pronounced industrial vibe. It would make an awesome movie set.

Charles Lemaresquier, early 20th-century architect of public buildings

Félix Potin flagship

The second half of the 19th century saw the birth of large department store such as Printemps. In this arena, Félix Potin was an extraordinarily successful dry-goods merchant who sold items mass-produced at his own manufactory.

Below is a Félix Potin retail store built in 1910 by architect Charles Lemaresquier. The lower part is relatively plain, but the upper part is something like Neo-Baroque, displaying the highly ornate style and prominent turret characteristic of Potin’s flagship stores. It’s an architectural mullet: business at the bottom, party at the top.

There’s something campy about the proliferation of details such as the giant urns and garlands, and the caduceus symbol (snakes entwined on a staff) in a large oval frame:

The caduceus is an attribute Mercury, patron of merchants and commercial success (among other things).

The Potin corporation finally went under in 1996, its departed soul perhaps guided to the underworld by Mercury the psychopomp.

Le Cercle National des Armées

Below, right: In 1927, Lemarasquier designed Le Cercle National des Armées, a hotel and social space for officers of the armed forces, located at Place St-Augustin next to l’Église Saint-Augustin.

The re-visioned Neoclassical architecture of Lemarasquier’s hotel echoes elements of Baltard’s Église St-Augustin: the church’s stained glass rose window is picked up by the hotel’s circular windows, and the church’s Romanesque arched portals are answered by the hotel’s own arched portals and windows.

Hôtel de Ville

Paris’ city hall was rebuilt 1873-1892 with a Renaissance Revival flavour. This structure also needs a post of its own.

More light for offices and factories

After the downfall of Emperor Napoleon III in 1870, the early years of the Third Republic saw a relaxation of Haussmann’s stringent building regulations. By comparison, many of these innovative and idiosyncratic structures along a block can appear jarring. Commercial and industrial buildings incorporated large metal-and-glass windows to increase interior illumination. There are great examples on Rue Réaumur, whose construction began in 1895, and which served as a matrix for architectural experimentation).

The 1899 office building below adapts some features of Haussmannian buildings for commercial use. The lower storeys have large windows, and the upper levels are designed more traditionally.

Below, variants in the evolution of the Paris apartment building, first quarter of the 20th century. Elaborate or eclectic, they no longer are bound to Haussmannian uniformity and display a plethora of approaches:

A flood of sunlight for residents: metal & glass box windows

For residential buildings constructed after about 1880, glass-and-metal box and bow windows were sometimes installed in vertical columns. They flooded the rooms of their residents with sunlight.

Architect Ferdinand Glaize designed the building below in 1891. Its unusual bow window is composed of metal, ceramic tiles, and glass.

The glass, metal, and polychrome features of these residential, commercial, and industrial buildings resonate with some aspects of Art Nouveau architecture.

Sculptural ornamentation

The Haussmannian project provided opportunities for sculptors to ornament new buildings and to have their work on permanent display for tout Paris.

Pride in work is evident in the architect and sculptor’s names carved onto the buildings below on Boulevard de Port-Royal:

Postscript

Islands of pre-Haussmannian facades

In the midst of Haussmannian streets, whether the architecture is regimented or cacophonous, you sometimes come across relaxed islands of surviving pre-Haussmannian buildings, such the short stretch on the north side of Boulevard St-Germain, between Rue de Buci and Rue de Seine:

Cul-de-lampe

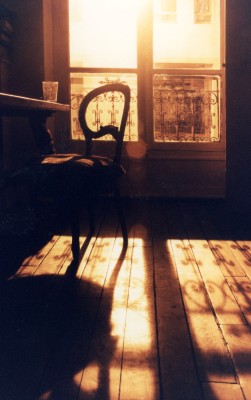

Below, amber light at sunrise (or sunset, I don’t remember) in an Haussmannian apartment in Belleville.

Next: Sexy Art Nouveau

Camille Martin