Desert Gold (collage by Camille Martin)

more collages

here

Gerhard Richter: Detail, 858-4

Scale

The

The red vowels, how they spill

then spell a sea of red

And the bright ships—

are they not ghost ships

And the bridge’s threads

against flame-scarred hills

And us outside

by other worlds

So

So the promise of happiness?

he asked a frog

then swallowed the frog

And the buzz of memory?

he asked the page

before lighting the page

And by night the sliding stars

beyond the night itself

A

A table erased

It is not realism makes possible the feast

Grey face turned away

Jam jar of forget-me-nots

Girl with gold chain

cinching her waist

But is it true

And what will become of us

As

As if the small voices—

one-erum two-erum

pompalorum jig

wire briar broken lock

then into and into

the old crow’s nest—

and so when young,

before all the rest

Crease

Crease in the snowy field

of evening within us

How the owl stares

and startles there

fashioning mindless elegy

So the remembered world’s

songs and flooded paths

This heap of photographs

This

This perfect half-moon

of lies in the capital

Crooks and fools in power what’s new

and our search has begun for signs of spring

Maybe those two bluebirds

flashing past the hawthorn yesterday

Against that, the jangle of a spoon in a cup

and a child this day swept out to sea

But

But the birth and death of stars?

The birds without wings,

wings without bodies?

The twin suns above the harbor?

The accelerating particles?

The pools of spilled ink?

Pages turning themselves

in The Paper House?

Soon

Soon the present will arrive

at the end of its long voyage

from the Future-Past to Now

weary of the endless nights in cheap motels

in distant nebulae

Will the usual host

of politicians and celebrities

show up for the occasion

or will they huddle out of sight

in confusion and fear

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Posted in poetry, visual art

Tagged art, Gerhard Richter, Michael Palmer, painting, poetry, Richter 858

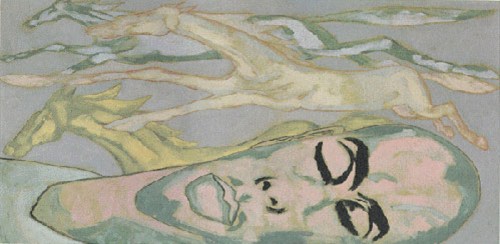

Francesco Clemente, from Anamorphosis

inside my head. I close my eyes.

The horses run. Vast are the skies,

and blue my passing thoughts’ surprise

inside my head. What is this space

here found to be, what is this place

if only me? Inside my head, whose face?

The remainder of poems and paintings in Anamorphosis can be found at 2River View.

This week I’m revisiting some collaborative pairings between poets and artists in other disciplines, in preparation for a collaborative performance series, Figure of Speech, that I’ve been asked to participate in. I’ll be working with a singer (who also plays the guitar), a guitarist who specializes in Baroque music, and a dancer. I want to address the things that can make an effective collaboration.

The 1997 collaboration between Robert Creeley and Francesco Clemente, Anamorphosis, strikes me as one of the most evocative and beautiful collaborations between a poet and a visual artist. I’m all for exquisite corpses and other processes incorporating chance, but there is something to be said for the way that Creeley and Clemente seem perfectly attuned to one another’s work. I don’t know whether Clemente made his paintings based on Creeley’s poems or vice versa, but they expand the meaning of one another through their sustained and rich dialogue. A good example is the first pair in the series, “Inside My Head.”

Clemente’s painting depicts a single image from Creeley’s poem: imagining horses. He gives a part for the whole, a relationship of synecdoche. Although the painting is a somewhat literal interpretation of Creeley’s imaginary horses, it doesn’t belabour that correspondence. Instead, the image is executed in such a way as to evoke other themes in the poem, such as mortality, identity, and imagination.

For example, in a painting whose colours are primarily pastel, the bold black lines depicting the closed eyes stand out, emphasizing the visionary quality of the man, which is also reflected in the poem. Clemente’s images of head and horses are elongated, further emphasizing painting and poem’s dreamlike quality. And the head of Clemente’s imagining man reclines with eyes closed, which could signify the shutting out of the world and the opening up of the world inside the head. It could also signify death or “death’s second self.” In all of these possible interpretations, the images sound sympathetic vibrations with the poem: death and the stuff of dreams.

As well, the simplicity of Creeley’s almost nursery rhyme-like poem with its repetitions and formal balance is well suited to Clemente’s simple but evocative image.

In depicting thoughts of running horses, perhaps these two had in mind Saussure’s use of the horse to describe the relationship between the referent (the external object, the actual horse), the signifier (the word “H-O-R-S-E”) and the signified (the concept of “horse”). Turning Saussure’s ideas on their head, Clemente and Creeley suggest that the signifier invokes the actual referent: Creeley doesn’t talk about thinking of horses, but instead there seem to be real horses running in the head. Similarly, Clemente’s painting depicts real horses galloping behind the speaker’s head.

Creeley also seems to be alluding to Andrew Marvell’s celebration of the world inside the head in “The Garden”:

Meanwhile the Mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness:

The Mind, that Ocean where each kind

Does streight its own resemblance find;

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other Worlds, and other Seas;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green Thought in a green Shade.

Green thoughts are echoed in Creeley’s poem in the speaker’s surprised blue thoughts.

In this dialogue with Saussure and Marvell, Creeley and Clemente assert the reality of the world of the imagination: that world possesses its own reality, and that reality is powerful, capable of extinguishing the exterior world through its concentrated focus on its thoughts and images. But it also spawns a meditation on the nature of personhood, cognition, and mortality.

The poem and painting of “Inside My Head” are both intensely interior and introspective, relieved only by Creeley’s paradoxical assertion of the commonality of the mystery at the heart of the human experience of subjectivity. Even inside the head, there is a “commons,” a place that is at once enclosed, private, subjective, as well as open, public, shared.

Creeley and Clemente’s collaboration is successful because the two works are in close dialogue with one another, which cannot happen if one simply holds up a mirror to the other.

Posted in painting, poetry, visual art

Tagged Camille Martin, collaboration, Francesco Clemente, painting, poetry, Robert Creeley, visual art

Posted in visual art

Tagged Antony Densham, Martin Davies, visual art, www.collageart.org

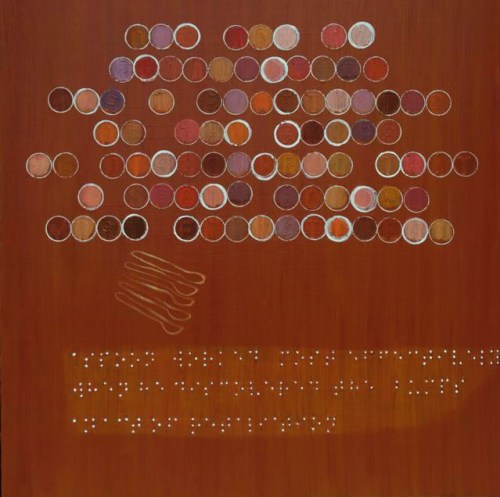

Gail Tarantino, One Act

In order to understand the interplay among the images in the three horizontal fields, it is necessary to decipher the Braille, something that I at first resisted. But my curiosity prevailed and I arranged the work on my screen next to a Braille alphabet and proceeded to decipher the sentence, letter by letter, yielding the following:

a spoon worked most effectively

when he discovered the bumps

an act of retaliation

As I progressed, the act of decoding it became easier, due to my increasing familiarity with the configuration of dots and the fact that after a few letters, guesswork came into play. A long word beginning with “effe . . .” can be guessed pretty accurately. But the slowness of my reading made me aware of how much take reading for granted, in a similar way that I take eating with a spoon for granted. Mulling over each letter in Braille slowed down the process. My brain, racing ahead of my slogging pace, was thinking of various possibilities, leading me to make incorrect assumptions a couple of times. I was taking too long to think about the text, so my mind was impatiently filling in the gaps in an effort to understand.

After deciphering the words, I realized that my effort was roughly analogous to a child learning to eat with a spoon: both are, as the title suggests, “one act.” This analogy is supported by the echoing of the shape of the Braille’s background colour, which is reminiscent of a spoon.

Tarantino compels viewers who do not know Braille to experience the unfamiliarity of the text and the opacity of its meaning until we decipher it, letter by letter. And in the act of doing so, we become conscious of the configurations of dots in each letter, recalling our original experience learning to read as a child, tracing the shape of each letter, as well as discovering the shape and usefulness of a spoon. Our reward is discovering something about writing as medium for communication, its thingy existence, as opposed to it being a system endowed with inherent meaning.

Significantly, the understanding of the Braille sentence is crucial to speculating on the meaning of the middle and top portions of the work. The middle portion consists of a series of spoons, one rather flat, like a knife, and the others in the familiar rounded concave shape.

The top half of One Act consists of scores of what look like little bowls. Some are missing, so that the pattern echoes the Braille in the bottom half. They are also different colours, resembling perhaps little pots of paint or perhaps bowls of soup, or food in the concave part of the spoon, the reward of the savvy child.

The question arises as to why Tarantino would describe the act of learning as on of retaliation, assuming that I am understanding the Braille sentence correctly. Retaliation requires first an act to retaliate against, so it seems plausible to assume that “he’ is retaliating against the opaque meaning of the spoon’s shape prior to his figuring it out, an opaqueness that strikes him as an act of hostility, which he counters by learning the usefulness of the spoon’s “bump.”

Carrying over the ideas in the message to the analogy of learning to read, the Braille sentence might suggest the concept of violence in the act of understanding. This idea is expressed in a set of conceptual metaphors in English, such as “to attack (or tackle, or surmount) the problem,” “to struggle with the meaning of something,” and “to fight ignorance.” These all suggest that understanding is a process of overcoming that which we don’t at first apprehend: the child “overcomes” the spoon’s unintelligibility; the uninitiated tackle the illegibility of Braille. And that violence is a retaliation against the violence of opacity, of being faced with something that is (at first) illegible.

Derrida’s theories on the violence of writing come to mind here, of writing regulating meaning, inscription as prohibition, law, circumscription. Before we deciphered the Braille, its meaning was opaque to us; it shunned our desire to understand it. Thus it might appear that Tarantino is turning the tables on the idea of violence inherent in writing, for the text (or the spoon) do their violence by remaining unintelligible, and the reader retaliates by learning and understanding. The violence of the reader is not the same as the violence of writing, for in Tarantino’s work, the reader’s violence is against illegibility. And meaning, interpretation, writing, and learning are not inherently acts of violence.

I may be overreaching in my musings here, and I certainly don’t mean to suggest that this is the only way of approaching this work. As One Act implies, there can be many different rewards to learning how to use a spoon, as the many bowls of soup in different colours attests, and by extension many different ways to understand a text.

In any case, I sense an acute intelligence at work in Tarantino’s work. It grapples with (to continue the conceptual metaphor) questions of representation, writing, legibility, and meaning in a condensed yet open-ended work. Did I mention that it’s also beautiful?

I highly recommend her website, where many of her works can be found:

Works consulted:

Derrida, Jacques. “The Violence of the Page.” Of Grammatology. Tr. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.

Marsh, Jack E. “Of Violence: The Force and Significance of Violence in the Early Derrida.” Philosophy and Social Criticism. 35.3 (2009): 269-286.

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca