Preface with Portraits

All images of work by Robert Zend are copyright © Janine Zend, all rights reserved, reproduced with permission from Janine Zend. Family photographs are reproduced with permission from Janine Zend, Natalie Zend, and Ibi Gabori.

Welcome to Robert Zend: Poet without Borders, my illustrated exploration of the life and work of the Hungarian-Canadian avant-garde writer and artist. The slide show above consists of photographs from Zend’s family and creative life as well as artistic portraits and self-portraits.

This project is the result of several months of research, interviews, and writing. It has become very dear to me, and I hope that you will enjoy the results. Over the next few weeks, I’m going to post installments, including biographical sections about Zend’s life in Hungary and Canada, and sections about his Hungarian literary roots, Canadian cross-pollination, and international affinities and influences.

I’ve had the pleasure and honour of speaking with members of the Zend family (Janine Zend, Natalie Zend, and Ibi Gabori) and of viewing texts, artworks, and other artifacts and memorabilia in the private collection of Janine Zend, for which I offer my deepest gratitude. I’ve also had the opportunity to research the extensive Zend fonds at the University of Toronto Library’s Media Commons. I’d like to thank curators Rachel Beattie and Brock Silversides, who had to put up with many a yelp of joy as I found such priceless artifacts as a photograph of Zend playing chess with the great French mime artist Marcel Marceau — on a chess set of Zend’s own design. These conversations and experiences have greatly enriched my understanding of the life, mind, and work of Robert Zend, for which I am very grateful.

As I worked on this project, I became acutely aware of my limitation of not knowing the Hungarian language. There are works by Zend in Hungarian that are as yet untranslated into English, and many documents in the Zend fonds that are written only in Hungarian. Nonetheless, I am fortunate that so much was either written by Zend in English or translated into English by him, often with the assistance of John Robert Colombo and others. I sincerely apologize in advance for any errors or omissions in what follows, and encourage correspondence from anyone with greater knowledge on the subject than I. If what I have written stimulates interest in Zend’s life and work, then I will consider my primary goal to have been accomplished.![]()

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the kind assistance and generosity of the following:

The family of Robert Zend: Janine Zend, Natalie Zend, and Ibi Gabori

Rachel Beattie and Brock Silverside, curators of the Zend fonds at Media Commons, University of Toronto Library

Edric Mesmer, Librarian at the University at Buffalo’s Poetry Collection and Curator of The Center for Marginalia, and the other wonderful librarians of The Poetry Collection for their research assistance

Brent Cehan of the Language and Literature division of the Toronto Reference Library

The Librarians in the Special Arts Room Stacks at the Toronto Reference Library

The Librarians at Reference and Research Services and at the Petro Jacyk Central and East European Resource Centre, Robarts Library, University of Toronto Libraries

Susanne Marshall (former Literary Editor for The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Irving Brown

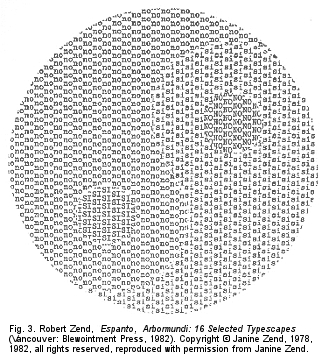

Robert Sward

bill bissett

Jiří Novák

Part 1. Linelife:

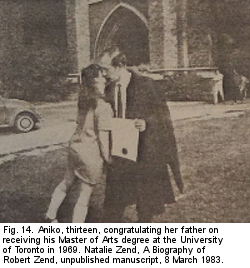

Premiere of a Rediscovered Treasure

I begin my series on the life and work of Robert Zend with the presentation of a previously unpublished short visual work entitled Linelife (1983), a flip-book animation sequence of dots and lines (fig. 1) that Zend dedicated to his daughter Natalie. I was excited to find Linelife in the Zend fonds at the University of Toronto.

Fortunately, Zend left instructions for its production. Although he had drawn the images in black ink on white paper, he preferred that the colors be reversed to white-on-black. So I digitalized the images and, according to his wishes, converted them into negatives. I thought that the digital medium would enhance the animated sequence of frames, so using film editing software I gave them a time-lapse animation to imitate the effect of flipping pages. Natalie made some excellent suggestions for the most effective presentation of the work. I hope that her father would have liked Linelife in this digital incarnation.

Fig. 1. Robert Zend, LineLife, ink drawing on paper, 1983, Box 10, Robert Zend fonds, Media Commons, University of Toronto Libraries. Adapted for digital medium by Camille Martin. Copyright © Janine Zend, 1983, all rights reserved, reproduced with permission from Janine Zend.

Although the narrative of Linelife unfolds in a geometrically abstract sequence of creation and disintegration, it also suggests an anthropomorphic trajectory of a life. And in fact, there exists a longer unpublished work entitled The Tense Present (fig. 2), which consists of the sequence of images in Linelife and interpellates text and other images to explore the arc of human life from conception to death.

Although the narrative of Linelife unfolds in a geometrically abstract sequence of creation and disintegration, it also suggests an anthropomorphic trajectory of a life. And in fact, there exists a longer unpublished work entitled The Tense Present (fig. 2), which consists of the sequence of images in Linelife and interpellates text and other images to explore the arc of human life from conception to death.

In the Linelife sequence above, which does not include that programmatic narrative, the gradual creation of a complex pattern of lines and dots could also suggest human creativity at work, and the deflation and ultimate disappearance of that triumphant pattern implies that in the cosmic order of things, art as well as life is short. Yet its very abstraction points to a more universal signification: the drama of development and decline, on microcosmic as well as macrocosmic scales. As well, the mirroring of the opening and closing suggests a cyclical pattern as things arise and fall apart in a continual succession of order and entropy.

I thought it appropriate to begin with this little gem because, although I know of no other flip-book in Zend’s oeuvre, its theme emblematizes his recurring concern with cycles of creation and destruction.

![]()

Part 2. Dissolving Labels and Boundaries

Being a poet does not depend on the geographical location of the poet’s body, or on the political system under which the publisher functions, but on the linguistic and literary value of the poems.1 —Robert Zend

Robert Zend (1929–1985) was a Hungarian-Canadian avant-garde writer and artist. As a young man of twenty-seven, he escaped his native Budapest during the 1956 failed Hungarian Uprising against Soviet rule and immigrated to Canada as a political refugee. He settled in Toronto, where he lived until his death in 1985. So nationality-wise, his life was divided into two parts: childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood in Hungary; and the rest of his life in Canada.

According to the convention of hyphenating nationality, Zend was indeed Hungarian-Canadian. However, considering his profound distrust of labels, the classification might have seemed an attempt to delimit him as a poet and human being. Because of his cosmopolitan outlook, I’ve come to think of him as a citizen of a realm expanded and enriched by his own generous sense of a borderless community of kindred poetic minds. And it is this generosity in his international affinities and aesthetic vision that I hope to develop in this essay.

It could be said that Zend had a somewhat conflicted relationship with nationality. Arriving in Canada as a political refugee, he celebrated the freedoms that had not been available to him in Soviet-controlled Hungary. And as an exile, he explored themes of alienation, loneliness, loss, and nostalgia for his native country — not unusual for immigrant writers.

On the other hand, having survived war-torn Europe, where totalitarianism and zealous nationalism had fostered a culture of xenophobia, racism, and hatred, and having seen the cruelties inflicted by the Nazi and then Soviet rule in Hungary, he understood all too well the catastrophic consequences of labeling people. He developed a distrust of boundaries, be they political, social, or aesthetic.

During World War II, more than 500,000 Hungarian Jews died as a result of the Nazi regime.2 And the Soviet Union, for all its propaganda of unity and egalitarianism, often used xenophobic fears to control the population, and under Stalin promoted an antisemitic campaign of murder and persecution.3 As well, many thousands of Hungarians labeled as “imperialist enemies” of the state were imprisoned, deported to forced labour camps, tortured, and executed, to say nothing of the more than 2,500 Hungarians killed during the 1956 Hungarian Uprising.4 Zend’s experiences of these brutal regimes provided cautionary models of zealous nationalism and racial paranoia and hatred.

One of Zend’s most poignant statements about labelling is in a speech for a panel on exile at the 1981 International Writer’s Congress. He speaks of totalitarian governments coming to power in Europe during the 1930s, which “began simplifying and polarizing the labelling of people”:

All labels — whether they were dignifying or humiliating — were meted out to certain groups, not because they did something good or evil, not because they deserved a reward or a punishment . . . but merely for circumstances beyond their control . . . like having been born into a rich or a poor family, into an Aryan or a Jewish family.5

From his experience of that catastrophic era in European history, Zend had developed a strong conviction of

the complete senselessness of labelling people according to nationality, place of birth, date of birth, religion, class, origin, sex, age, the colour of skin, the number of pimples, or whatever.6

So it’s not surprising that his life’s work dissolves boundaries, and in this essay I will explore three ways in which he did so.

First, his outlook was international, starting with his high school and university studies of Italian literature and readings of world literature in Hungary. And after Zend’s arrival in Toronto, Zend sought not only Canadian affinities but also artistic and literary friendships and inspiration around the world, perhaps most significantly with Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges but extending to writers, artists, and traditions in other countries such as France, Italy, Belgium, and Japan. Zend, no respecter of cultural boundaries, enthusiastically sought out the literature and art of other nations.

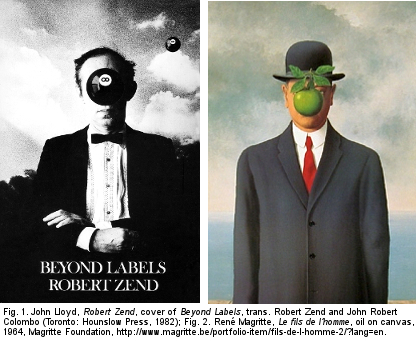

Indeed, Zend’s first poetry collection, From Zero to One, reveals something of his cosmopolitan openness. He shows his indebtedness to Canadian influences with poems dedicated to Raymond Souster, Marshall McLuhan, Norman McLaren, Glenn Gould, John Robert Colombo, and professors of Italian studies J. A. Molinaro and Beatrice Corrigan. The dedications of other poems demonstrate Zend’s affinities with cultural figures from the United States (Saul Steinberg, Isaac Asimov, and Arthur C. Clarke), France (Marcel Marceau), Belgium (René Magritte), Hungary (science writer Steven Rado, actor Miklós Gábor, and artist Julius Marosán), and ancient Greece (Plato). The title of the book comes from a poetic essay by Frigyes Karinthy, who, as I will explore in greater detail in an upcoming installment, was an important Hungarian literary influence. And the dust jacket bears an exquisite portrait of Zend by French mime artist Marcel Marceau.

His tributes to writers and artists sometimes takes the form of collaboration, strikingly in the case of Borges and Marceau, and ekphrastic poems, as in his response to the paintings of Belgian artist René Magritte, Hungarian-Canadian artist Marosán, and Spanish-Canadian artist Jerónimo.

Secondly, his writing thematically dissolves geographical, political, and social boundaries to explore humanity’s place within the cosmos as well as fantastical realms that often involve dreams and time travel. He writes more traditionally about such subjects as romantic relationships and the dilemmas that he faced as an immigrant, but many other works develop philosophical concepts about the connectedness of all persons to one another and to the universe.

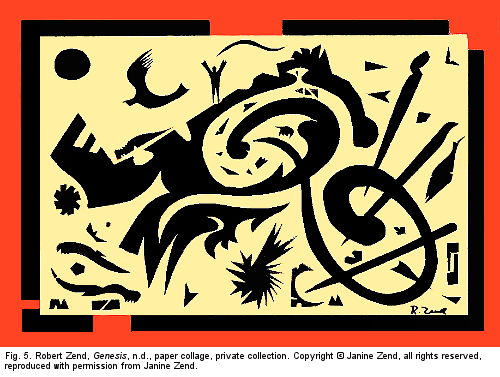

Thirdly, Zend was a polymath, and he used whatever materials were at hand to create works that are multi-genre and multi-media. During his twenty-nine years in Canada he wrote poetry, essays, fiction, and plays; created collages and concrete poetry; used found objects such as cardboard tubes for creating three-dimensional visual poetry; and researched, wrote, directed, and produced over a hundred cultural documentaries for the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC). He was also a musician, filmmaker, and self-described “inveterate doodler.”7 A multi-media artist and chess player, he designed a chess set to be presented by the CBC to Marceau during his 1970 visit to Canada.8 And some of his works defy classification, such as the two-volume multi-genre Oāb (1983, 1985).

Zend’s cosmopolitan attitude is rooted in childhood and early adulthood experiences that nurtured in him an openness to cultural influences regardless of national boundaries. For Zend, love of city, region, or homeland, or of the culture associated with those places, is accompanied not so much by feelings of pride as by the desire to seek out affinities with writers and artists without regard (as he puts it) to “nationality, place of birth, date of birth, religion, class, origin, sex, age, the colour of skin, the number of pimples, or whatever.”

Coming Up . . .

The next two installments of my essay will highlight some major events in Zend’s life, giving biographical context to what follows, as well as offer an overview of his published works.

The last installments will be devoted to the heart of my endeavour, in which I trace some of Zend’s literary affinities and influences, with special emphasis on his roots in Hungary, his transplanted roots in Canada, and his alliances with writers, artists, and cultural traditions worldwide, with particular emphasis on Argentina, France, Italy, Japan, and Belgium. And in some of the samples from his writing, you’ll see some of his cosmic and fantastical concerns. As well, I’ll reveal ways in which his visual work crosses boundaries of genre and discipline.

A Note about Cosmopolitanism

My use of the term “cosmopolitanism” refers to a historically situated discussion in Canadian culture that came to the fore during the 1940s. The debate between the proponents of a national, nativist literature and the advocates for a more cosmopolitan view intensified when A. J. M. Smith threw down the gauntlet in favour of the latter in his 1943 anthology, The Book of Canadian Poetry. Post-World War II, this debate defined two overarching trends in Canadian poetry criticism: the desire for a national literature rooted in autochthonous themes and imagery, versus a more cosmopolitan spirit of poetry aware of currents of thought in international modernism and embracing their influence. While it is not my purpose to enter into a detailed theoretical and historical explanation of these trends, I wish to set the stage for the strong view of nationalism that gained steam with the aftermath of the Massey Commission since the 1950s, as this is the historical period that Robert Zend entered when he immigrated to Canada in 1956. My use of the term “cosmopolitan” to describe Zend’s cultural outlook does not in any way denigrate regionalism or nativism in content or aesthetic approach (or imply that Zend did so); neither does it suggest that Zend, as a political refugee from Hungary, did not admire and absorb lessons from the literature and art produced within Canadian borders. I hope to demonstrate in my analysis quite the contrary.

Part 3. Hungary: Childhood and Early Adulthood

Little has been publicly known about Robert Zend’s early years in Hungary, prior to the 1956 Uprising and his subsequent immigration to Canada. I’d like to begin the process of fleshing out this period of his life. Some of the biographical material from this period will help us to understand the shaping of his cosmopolitan outlook. In addition, some background on his life in both Hungary and Canada will help to contextualize my subsequent discussion of his international affinities and influences. Robert Zend was born in Budapest, the only child of Henrik and Stephanie. Most sources indicate that he was born on December 2, 1929. However, there is some uncertainty about the date. Henrik, the youngest among many brothers and sisters, married late in life, so that Robert’s cousins were ten to twenty years older than he.1 Thus during his early years, Robert was often in the midst of adults.

Robert Zend was born in Budapest, the only child of Henrik and Stephanie. Most sources indicate that he was born on December 2, 1929. However, there is some uncertainty about the date. Henrik, the youngest among many brothers and sisters, married late in life, so that Robert’s cousins were ten to twenty years older than he.1 Thus during his early years, Robert was often in the midst of adults.

Zend points out the irony of his given name. Henrik had wanted to call him James after his own father. But his brother-in-law Dori argued against it because it sounded so old-fashioned. Henrik didn’t like Dori’s suggestion of a common name for his son, who would surely be distinguished. Finally,

Dori proposed to him the name Robert which in those times and in Hungary was a modern, but very rare, almost exotic name. My father readily agreed because his favourite composer was Robert Schumann. Had he known that I would spend most of my life in North America where every second male is called Robert (or even Bob!), he wouldn’t have compromised so easily.2

Zend wryly observes that had his father favoured a different composer, his name might have been “Johann Sebastian Zend.”

Henrik, fluent in five languages, worked as a foreign correspondence clerk for a rice mill, and Stephanie was a homemaker.3 They were not well off, and after the birth of Robert, one month after the New York Stock Market crash of 1929, they faced economic difficulties and uncertainty. The ensuing global depression devastated the Hungarian economy: by 1933, Budapest had a poverty rate of 18% and an unemployment rate of 36%.4 Following a failed pregnancy, Henrik and Stephanie decided not to have additional children.5

Zend wrote about the sibling that he never had in a poignant story entitled “My Baby Brother”: he dreams that his parents have come back to life, and even at their advanced age they bear a son, who he imagines “will be a better man than me, a second, corrected edition of me.”6 Other works develop the theme of existence foiled, as in “The Rock,” a story about a dreamed Jesus who has missed his chance to be born:

Time was pregnant.

It was predetermined that he was to be born. The day and the hour and the minute and the second had been decided. The land and the city and the house assigned. The father and the mother chosen.

But something somewhere, something went wrong. His dreamer — in a higher consciousness — woke up with a start before dreaming his birth, and by the time he succeeded in sinking back into the dream again, the point was passed.7

And in “The Most Beautiful Things,” he ponders all of the art and life that remain in a limbo of unfulfilled potentiality:

My most beautiful poems are never written down

I am afraid to commit them to a prison of twenty-six lettersIn the same way

the most beautiful statues on earth hide

in uncarved rockThe most beautiful paintings

are all crammed together in tiny tubes of paintThe most beautiful people will never be born8

In such works, it is as though a parallel universe contained all the possibilities that never came to fruition. Yearning for the unborn baby brother was not the only experience to which one could ascribe Zend’s sense of what he elsewhere calls “historical unhappenings.”9 As we will see, it was one of other events to come that would mark him with an indelible awareness of thwarted possibilities.

Robert’s early years held much promise. The foundation for his love of Italian culture and literature was laid in childhood. Henrik brought him to Italy at the ages of ten and twelve to stimulate the boy’s interest in learning the Italian language.10 Zend describes himself during childhood as a social misfit as he wasn’t interested in playing sports with other boys. As a result of his introversion, Henrik and Stephanie suspected that their son was socially stunted as well as intellectually slow, and planned to take him out of school after the fourth grade to apprentice with a carpenter. However, Robert began to display talent in languages and to demonstrate more than a superficial interest in literature. When he was seven, he impressed his teacher and classmates with his language skills. At the age of eight, the precocious boy recited from memory a 140-line poem by nineteenth-century Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi.11

Zend describes himself during childhood as a social misfit as he wasn’t interested in playing sports with other boys. As a result of his introversion, Henrik and Stephanie suspected that their son was socially stunted as well as intellectually slow, and planned to take him out of school after the fourth grade to apprentice with a carpenter. However, Robert began to display talent in languages and to demonstrate more than a superficial interest in literature. When he was seven, he impressed his teacher and classmates with his language skills. At the age of eight, the precocious boy recited from memory a 140-line poem by nineteenth-century Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi.11

After Robert finished the fourth grade, Henrik and Stephanie reconsidered the plan to withdraw him from school to learn a trade. Having observed his talents and listened to the entreaties of his teacher, they were convinced to cultivate the boy’s intellectual gifts rather than apprentice him to a carpenter.

Robert began to play the piano by ear at the age of ten. Although he never learned to read scores, he excelled at imitating pieces he heard, such as Mozart’s “Turkish March,” and composing songs. Family and friends thought that Robert was destined to become a concert pianist, but even in early adolescence, Robert knew that he would be a writer.12

When Robert was fourteen, his father placed him in Regia Scuola Italiana, the Italian high school in Budapest, so that he could become fluent in a second language; there Zend also studied Latin and German. One of his professors was Joseph Füsi, a prominent translator of plays by Luigi Pirandello. Zend describes Füsi as a personal friend who encouraged him to write and translate.13

Childhood travels to Italy and studies at the Italian high school fostered in Robert an enduring love of languages. He went on to study literature in several other languages and twenty years later earned a graduate degree in Italian literature at the University of Toronto. His high school studies with Füsi likely influenced his decision to write about Pirandello for his master’s thesis.

Robert seems to have had a happy childhood, nurtured by caring parents who assiduously looked after his health, well-being, and education. Although they could scarcely afford it, they sent him at ages one-and-a-half and six to the beach towns of Grado, Italy, and Laurana, Yugoslavia, respectively, to recover from rickets (a bone disease caused by a deficiency in vitamin D). His father took him on two more trips to Italy to expose him to a different language and culture. And when Robert was in the seventh grade, they hired a private tutor to help him with Latin when his grades in that subject flagged.14

He remembers fondly that his mother spoiled him. However, she also tended to be over-protective, even accompanying him when he was fourteen to summer camp, where his father had sent him to gain a sense of independence. Teased about his hovering mother, Robert resourcefully wrote to her older brother, Dori, for help. His uncle understood the situation and quickly persuaded his sister to leave her son in peace. After her departure, Robert was able to bond with the other boys.15

Reminiscences of his parents and childhood surface in some of his stories and poems. In “A Memory,” he tells of a humorous (in retrospect) coming-of-age incident involving his father:

Once, at fifteen,

I made my poor

old dad so mad at methat he chased me

around the table

till I caught him, finally16

And in “Madeleine,” he experiences a self-referential Proustian moment eating a madeleine and remembering himself at fifteen reading Proust in his parents’ “old apartment” in a “yellow house [on a] curvy little street.” He recalls the magic of his youth in Budapest, and “my mother, my father, my friends and my loves.” He decides to write his memoirs, to be entitled (in typical Zend brain-teaser fashion) In Search of In Search of Time Lost Lost.17 However, the peace of those years was shattered with Hungary’s turbulent entrance into World War II. The years from 1944 to 1945 saw not only the Nazi takeover of Hungary and the deportation and murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews and others deemed undesirable by the regime, but also the Soviet invasion of Hungary (between October 1944 and February 1945) and its aftermath of rape, murder, and pillage. The Siege of Budapest by the Soviet military was one of the longest and bloodiest urban battles of World War II in Europe (fig. 4). The extraordinarily violent and chaotic transition from Nazi to Soviet control lasted about one hundred days and resulted in extremely degraded living conditions amid destruction, terror, disease, and starvation. Atrocities against civilians were committed by both Hungarian and Soviet forces. During the Siege, about 38,000 Hungarian civilians were killed. Thousands were executed outright by members of the Arrow Cross, the pro-Nazi Hungarian party.18

However, the peace of those years was shattered with Hungary’s turbulent entrance into World War II. The years from 1944 to 1945 saw not only the Nazi takeover of Hungary and the deportation and murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews and others deemed undesirable by the regime, but also the Soviet invasion of Hungary (between October 1944 and February 1945) and its aftermath of rape, murder, and pillage. The Siege of Budapest by the Soviet military was one of the longest and bloodiest urban battles of World War II in Europe (fig. 4). The extraordinarily violent and chaotic transition from Nazi to Soviet control lasted about one hundred days and resulted in extremely degraded living conditions amid destruction, terror, disease, and starvation. Atrocities against civilians were committed by both Hungarian and Soviet forces. During the Siege, about 38,000 Hungarian civilians were killed. Thousands were executed outright by members of the Arrow Cross, the pro-Nazi Hungarian party.18 Tragically, Robert’s parents were among those killed during that brutal period.19 The shock and grief of his loss left a deep impression on him for the rest of his life.

Tragically, Robert’s parents were among those killed during that brutal period.19 The shock and grief of his loss left a deep impression on him for the rest of his life.

In the semi-autobiographical story “My Baby Brother,” Zend directly addresses his parents’ death, interweaving with that event an account of his brother who died before birth. As mentioned previously, the story tells of dreamer who learns that his long-dead parents have returned to life and immediately become pregnant with a boy. Although he is excited at the thought of having a baby brother, he also realizes that this sibling will replace him and accomplish all the things he was unable to, such as becoming a “great composer” because “internal and external forces prevented me from doing so.” Like a Twilight Zone episode, the dream keeps returning to the beginning, and the details of his parents’ demise shift: they died in a camp, they were shot, their apartment was bombed. And he learns of their last words: hopes for their son’s survival. And since their deaths, he says,

they’ve been my guardian spirits, floating around me, saving me from death on ten or so occasions.20

The dreamer is trapped inside a tape loop, an endless rehearsal of variations on tragedy, not unlike the history of Hungary in the twentieth century. Finally, the dream ends with a scene of a tombstone whose inscription keeps changing. He’s not sure whose tombstone it represents: the baby brother he never had? Or perhaps the dead avenues of a life of foiled plans? The former emblematizes the latter, and from Zend’s multiple losses emerges the recurring theme in his writing of the “unborn child” who “knocks at the gates of existence,” “struggl[ing] to become,” but who ends up “freezing on the snow-fields of white non-existence.”21

The end of the Nazi’s brief but barbaric chapter in Hungary’s history was following by a protracted Communist totalitarian regime with its own institutionalized system of cruelty and deception. And although life was not easy during Budapest’s long recovery from the destruction and devastation of the war, Zend was able to continue his education. In 1949, he was admitted to Péter Pázmány Science University, where he completed three years of study in Hungarian and Italian literature, and four years of study in Russian literature. In addition, he studied German, Finnish, and classical languages.22

Soon after he began his university studies, he married Ibi Keil in 1950. Ibi and Robert had been drawn together by their love of classical music and literature. When they met, Robert was entertaining friends by playing a Mozart piano sonata. Ibi recalls that Robert was impressed by her ability to sing melodies from all of Beethoven’s symphonies. On one of their first dates, they attended a performance of The Tragedy of Man by Imre Madách, the famous nineteenth-century Hungarian poet whose long dramatic poem, as we will see later, deeply influenced Zend’s writing and art. And they also shared feelings of empathy for the tragic events of their youth: Robert had lost his parents to the war, and Ibi had lost her parents, younger brother, and other family members to the Holocaust. In 1944, at the age of fifteen, Ibi had been transported along with her parents and brother to Auschwitz. She managed to live through the horrors of Auschwitz and two other camps, but unfortunately her parents and brother did not survive.23

Although apartments were hard to come by, the young couple, assisted by an uncle of Robert’s, managed to procure a small place. They settled into their new life together as Robert continued his studies and Ibi worked at a factory while pursuing her own education to become a librarian.24

In 1953, Zend received a Bachelor of Arts degree as well as the official title of Literary Translator. One of his university professors was Tibor Kardos, who edited the literary magazine where from 1953 to 1956 Zend worked as a translator of Italian literature.25 For four years, from 1948 to 1951 (between the ages of 19 and 22), he worked for the Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, the state-controlled cinema during the Stalin regime, where he edited films, designed and produced dozens of movie posters, and wrote film reviews.26 Although many of these films appearing from the state monopoly were vehicles for political messages, for a brief time early into the Communist regime, a variety of more sophisticated films was allowed, as the poster produced by Zend of Hamlet (1948, starring Lawrence Olivier and Jean Simmons) attests (fig. 6). In the same year, he also produced a poster for Talpalatnyi föld (Treasured Earth), the first film realized by the newly nationalized film industry in Hungary (fig. 7).

For four years, from 1948 to 1951 (between the ages of 19 and 22), he worked for the Press and Publicity Department of the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company, the state-controlled cinema during the Stalin regime, where he edited films, designed and produced dozens of movie posters, and wrote film reviews.26 Although many of these films appearing from the state monopoly were vehicles for political messages, for a brief time early into the Communist regime, a variety of more sophisticated films was allowed, as the poster produced by Zend of Hamlet (1948, starring Lawrence Olivier and Jean Simmons) attests (fig. 6). In the same year, he also produced a poster for Talpalatnyi föld (Treasured Earth), the first film realized by the newly nationalized film industry in Hungary (fig. 7).

But working conditions were far from ideal, as many of the films approved by the state were monotonously devoted to praise of Communism and condemnation of its enemies. Moreover, Zend had to deal with narrow-minded and incompetent administrators at the Hungarian National Filmmaking Company. For Zend, the position was neither a creative nor a worker’s paradise. He made his job tolerable by entertaining friends with satirical reviews of the films with the most hackneyed ideological plots, and joking about the “waterhead” administration, so-called because “the department bosses seemed to have heads made of water.”27

Someone as outspoken as Zend was bound to come into conflict with officials, and before long he was blacklisted by the Communist administration, which meant that he was effectively barred from securing full-time employment. The event that triggered the blacklisting might seem innocent enough. The government had set up a wall on which the public was invited to write constructive criticism of government services and other socialist functions. Zend had written a bitingly satirical criticism of food that was served at a political event. The officials were not amused, and Zend was fired and prevented from pursuing any kind of meaningful career.28 To earn sufficient income to help support himself, his wife, and in 1956 their newborn baby, he had to patch together a variety of short-term and part-time jobs. For four years, he worked as a free-lance journalist. In addition, he did writing and editorial work for children’s and youth magazines, edited books for the Young People’s Book Publisher, wrote reports and essays for a teacher’s magazine, wrote for the Hungarian Radio, translated poetry and essays from German, Italian, and Russian sources into Hungarian, and worked with illustrators, artists, and printing shops.29 One of his editing jobs, for example, was a 1955 guide book for the Pioneers, a socialist youth group (fig. 8).

To earn sufficient income to help support himself, his wife, and in 1956 their newborn baby, he had to patch together a variety of short-term and part-time jobs. For four years, he worked as a free-lance journalist. In addition, he did writing and editorial work for children’s and youth magazines, edited books for the Young People’s Book Publisher, wrote reports and essays for a teacher’s magazine, wrote for the Hungarian Radio, translated poetry and essays from German, Italian, and Russian sources into Hungarian, and worked with illustrators, artists, and printing shops.29 One of his editing jobs, for example, was a 1955 guide book for the Pioneers, a socialist youth group (fig. 8).

He loved writing for children, and a friend who edited the chilren’s magazine Pajtás (Pal) helped him to get paid for writing articles.30 Zend reports that his pen name, “Peeper,” was “extremely popular,” and he received fan mail from children all over Hungary.31 He also travelled regularly to visit schools around the country.32

Zend was also developing as a poet. He wrote his first poems at the age of nine and thirteen and began writing poetry in earnest when he was fifteen,33. A meeting with his literary idol, Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy, made a lasting impression on him.34. During the 1950s, he continued to write poetry, in these earlier years verse of a lyric nature.35

In 1956, Ibi fulfilled two dreams. After the loss of so many of her relatives to the Holocaust, she longed to start a family. After years of despairing that it might not be possible for her to have children due to the damage her body had sustained in Nazi labour camps, she finally became pregnant with a girl. In the same year that Aniko was born, Ibi fulfilled her long-time dream of becoming a librarian after passing her exams.36

For the Zends, the years leading up to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution were not easy. Money was so tight that Robert wasn’t even able to afford a typewriter, which would have cost the couple three months’ wages. Something as basic to a poet as a typewriter was a “lifetime ambition.”37 In February 1956, Aniko was born premature, and Ibi describes her during the first eight months as “very thin, very pale, and undernourished,” as the baby didn’t have the proper food and vitamins to thrive.

Discontent with Soviet rule was rampant, and during the summer and fall of 1956 it grew increasingly bold and vocal. Leafing through children’s books that she was placing back on the shelves, Ibi noticed that even the children were scribbling protests about the government’s hypocrisy:

Wherever there was anything praising Communism, the Russian army or the Kremlin’s might, the little children had written in, “It’s not true . . . All lies . . . We don’t want Russia.”38

In 1956, Robert was on the brink of publishing his first book, a collection of one hundred poems, with a dissident publishing company, when a landmark event in Hungarian history suddenly halted his plans.39 His and Ibi’s lives were forever and drastically changed as a result of the Hungarian Uprising against Soviet rule. Journalists and university students, encouraged by the June uprising in Poland against the Soviets, began openly to question and debate the future of Hungary. On October 23, students marched to the Parliament Building to voice their protest and list their demands for the sovereignty of Hungary, free elections, freedom of the press, and various individual freedoms severely eroded by Soviet rule (fig. 9). The demonstration ended in a massacre when government snipers and Soviet tanks opened fire on the crowd, leaving about one hundred students dead.

In 1956, Robert was on the brink of publishing his first book, a collection of one hundred poems, with a dissident publishing company, when a landmark event in Hungarian history suddenly halted his plans.39 His and Ibi’s lives were forever and drastically changed as a result of the Hungarian Uprising against Soviet rule. Journalists and university students, encouraged by the June uprising in Poland against the Soviets, began openly to question and debate the future of Hungary. On October 23, students marched to the Parliament Building to voice their protest and list their demands for the sovereignty of Hungary, free elections, freedom of the press, and various individual freedoms severely eroded by Soviet rule (fig. 9). The demonstration ended in a massacre when government snipers and Soviet tanks opened fire on the crowd, leaving about one hundred students dead. As a result of the massacre, widespread and violent protests erupted as outraged Hungarians witnessed the extent to which the Soviets were determined to maintain their grip on the satellite country.40 During the revolt, which lasted from October 23 to 28, 1956, Hungarians engaged in fierce battle with Soviet tanks and soldiers. Victorious citizens clambered onto captured Soviet tanks and waved the Hungarian flag with the detested hammer and sickle cut from its center (fig. 10).

As a result of the massacre, widespread and violent protests erupted as outraged Hungarians witnessed the extent to which the Soviets were determined to maintain their grip on the satellite country.40 During the revolt, which lasted from October 23 to 28, 1956, Hungarians engaged in fierce battle with Soviet tanks and soldiers. Victorious citizens clambered onto captured Soviet tanks and waved the Hungarian flag with the detested hammer and sickle cut from its center (fig. 10). By October 28, Hungarian fighters had suffered heavy losses but appeared to have been successful: the tanks withdrew from Budapest and the citizens enjoyed a few days of freedom from Soviet aggression. Ibi remembers the kettles that people placed on street corners to collect money for the widows and children of those killed in battle (fig. 11), and that there was a euphoric feeling of solidarity and mutual trust.41 As the Soviet government officially admitted mistakes in handling the uprising and announced its intention to negotiate with Hungarian officials regarding Soviet military presence, the prospect of a sovereign and independent Hungary, free from Soviet interference, was openly celebrated.42

By October 28, Hungarian fighters had suffered heavy losses but appeared to have been successful: the tanks withdrew from Budapest and the citizens enjoyed a few days of freedom from Soviet aggression. Ibi remembers the kettles that people placed on street corners to collect money for the widows and children of those killed in battle (fig. 11), and that there was a euphoric feeling of solidarity and mutual trust.41 As the Soviet government officially admitted mistakes in handling the uprising and announced its intention to negotiate with Hungarian officials regarding Soviet military presence, the prospect of a sovereign and independent Hungary, free from Soviet interference, was openly celebrated.42 However, unbeknownst to Hungarian civilians, on November 3 Khrushchev approved Operation Whirlwind, a Soviet military invasion of Hungary involving sixty thousand soldiers. Early in the morning on Sunday, November 4, without warning, hundreds of tanks rolled into Budapest in a swift and brutal crackdown on the Hungarian Revolution (fig. 12), assisted by the AVO (Hungarian secret police). Many Hungarians actively resisted with guns and Molotov cocktails. It was an extremely perilous time: thousands of Hungarians were killed by superior Soviet power, and the dreaded AVO ruthlessly tortured their own compatriots whom they deemed to be enemies of the socialist state. The Soviet Minister of the Defense estimated that within three days the soldiers would have the city under control; in fact, the Hungarian insurgents kept fighting until November 11.43

However, unbeknownst to Hungarian civilians, on November 3 Khrushchev approved Operation Whirlwind, a Soviet military invasion of Hungary involving sixty thousand soldiers. Early in the morning on Sunday, November 4, without warning, hundreds of tanks rolled into Budapest in a swift and brutal crackdown on the Hungarian Revolution (fig. 12), assisted by the AVO (Hungarian secret police). Many Hungarians actively resisted with guns and Molotov cocktails. It was an extremely perilous time: thousands of Hungarians were killed by superior Soviet power, and the dreaded AVO ruthlessly tortured their own compatriots whom they deemed to be enemies of the socialist state. The Soviet Minister of the Defense estimated that within three days the soldiers would have the city under control; in fact, the Hungarian insurgents kept fighting until November 11.43

It was also a perilous time for Zend, who had been producing and distributing leaflets encouraging Hungarians to revolt.44 If he were discovered and arrested, he could have been severely punished as a traitor.

Furthermore, Ibi recalls her feelings of anxiety when accompanying the Soviet invasion came a renewed wave of antisemitism with ominous slogans appearing on walls such as “Icig, Icig,45 most nem viszünk Auschwitzig!” (“Jews, this time you won’t even have to go to Auschwitz!”), intimating the possibility of a return to the days of the Arrow Cross terror of 1944—1945.46 Such threats, as well as serious antisemitic incidents, which were occurring in small Hungarian towns as well as in Budapest, sent a chill of fear through the surviving Jewish population in Hungary. In some cases, mobs roamed the streets of small towns attacking Jews and their homes and businesses.47 This danger as well as the Soviet invasion were factors in the Zends’ decision to leave Hungary.48

Escape was possible if risky: if people walked all or part of the way, they faced the risk of hypothermia and exhaustion as it was the onset of winter; they were also in peril of being captured or shot by AVO border patrols. Hungary was bordered to the north by Czechoslovakia, and to the east by the Soviet Union and Romania. The main directions toward freedom were to the west, toward Austria, or to the south, toward Yugoslavia. The vast majority of the 200,000 Hungarian refugees fled to Austria.49

Zend could envision the bleak and undignified future for writers and other intellectuals in Hungary. Indeed, after the Soviets regained control of Hungary, many writers were arrested and sentenced to many years in prison, and in January 1957, the Writers’ Association and Journalists’ Union were disbanded by the Soviet-controlled government.50 Zend did not want to live under a regime in which his every word would be scrutinized and subject to state censorship. As he writes in Beyond Labels, the refugee Hungarians crossed the Atlantic

to get away from the land

where there wasn’t enough room for us

in the houses and on the streets —

where armies every decade changed their shirt colours

and massacred us again and again —

where even the trees eavesdropped on us

whispering behind our backs —

where at night what was left of our souls

kept on trembling in fear —51

As to his own decision to go into exile, he states,

I chose to leave my country rather than publish party-line poetry or publish dissident poetry and be jailed, or deported, or silenced afterwards.52

For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and eight-month-old baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria. A close friend, István Radó, had created fake identification papers for the escape of twenty to thirty persons, and invited Robert and his family to join the group. Fig. 13 shows the card he forged for the Zends, certifying that their apartment had been destroyed, rendering them homeless, and authorizing travel.

For a brief window of opportunity, he and his wife and eight-month-old baby had the chance to escape westward into Austria. A close friend, István Radó, had created fake identification papers for the escape of twenty to thirty persons, and invited Robert and his family to join the group. Fig. 13 shows the card he forged for the Zends, certifying that their apartment had been destroyed, rendering them homeless, and authorizing travel.

Ibi still vividly recalls the events of their escape.53 She and Robert joined István’s group in a covered truck and hired driver. The mood was somber as she watched the cobblestones retreating through the fog as the truck drove the group of friends away from Budapest and toward Austrian border. They proceeded along back roads, taking advice along the way from fellow Hungarians about which routes were blocked by the Soviets. In the event they were stopped by Soviet soldiers, Robert and István had written a letter in Russian addressed to the soldiers (fig. 14), pleading with them to let them go on their way: “Dear Soviet Soldier, We are all ordinary Hungarian workers. Fathers, mothers, children, families, who lost everything—shelter and furniture, earned with hard labour. None of us fought against you. We are not fascists or partisans. We love you as you are also workers—providers for your families. We don’t like capitalists or imperialists. Our only wish is working in peace another twenty-thirty years. Our lives now are in your hands. If your hearts are opened up to love and you also love your family, you will help us and get our gratitude. We call on you, dear Soviet Soldier, help us! In the name of our children!!! Ordinary Hungarians”54

In the event they were stopped by Soviet soldiers, Robert and István had written a letter in Russian addressed to the soldiers (fig. 14), pleading with them to let them go on their way: “Dear Soviet Soldier, We are all ordinary Hungarian workers. Fathers, mothers, children, families, who lost everything—shelter and furniture, earned with hard labour. None of us fought against you. We are not fascists or partisans. We love you as you are also workers—providers for your families. We don’t like capitalists or imperialists. Our only wish is working in peace another twenty-thirty years. Our lives now are in your hands. If your hearts are opened up to love and you also love your family, you will help us and get our gratitude. We call on you, dear Soviet Soldier, help us! In the name of our children!!! Ordinary Hungarians”54

Fortunately, they didn’t have to use the letter, as they made their way toward the border unchallenged. However, the driver, after having promised to convey them to the border, stopped a few miles short of it and refused to go any farther. Despite feeling betrayed, the group paid him the agreed-upon fee and were compelled to walk for a few hours the rest of the way through rain and mud.

They had to face one last danger when, just before arriving at the Austrian border, they were halted by a guard, a young Hungarian who had been conscripted into service to prevent his fellow countrymen from escaping. Fortunately, one of their group managed to talk (and bribe) the young man into allowing them to go peacefully on their way, persuading him that their homes had been destroyed and reassuring him that when the situation in Budapest had calmed down, they would return to Hungary — after all, he reasoned with the guard, they were patriotic Hungarians and would not desert their country forever. The bluff and bribe together softened the guard, who allowed them to continue. Finally the group crossed the border, where Austrians approached them with words of welcome and led them to American and Canadian Red Cross shelters and warm food. Such was Ibi’s relief at their safe passage that she fell to her knees and began laughing uncontrollably.

Canadian and American immigration officials were stationed at the refugee camp, conducting preliminary interviews. Although the Zends had a choice of immigrating to either country, their decision to go to Canada was determined during their interview with the Americans. In 1956, McCarthyism was still casting strong suspicion on any American deemed to be associated with the Communist Party, and thus the American interviewers wanted to know the Zends’ affiliation with and allegiance to the Communist Party of Hungary and the Soviet Union. Ibi, who had been raised in a poor family, was able to get a college education and become a librarian due to the assistance and subsidy of the Hungarian Communist government. If she were to lie, denying that Communism had helped her to achieve her dream, the Americans would accept her as a political refugee.

But the flip side of life under Communism was a web of lies, a suppression of truth in order to maintain a façade of harmony and prosperity. Ibi, weary of such deception, refused to conceal from the Americans her gratitude for the benefits she had derived from the Communist educational program in order to satisfy them that she would be an acceptable immigrant. Thus Ibi’s sense of integrity sealed the Zends’ decision to go to Canada.

From the border Red Cross camp they traveled by train to Vienna, along with other refugees, where they stayed until their immigration paperwork was processed and they were ready to travel to their destination (fig. 15).

In Vienna, many voluntary agencies had quickly organized to provide relief for the refugees, such as the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the Lutheran World Federation, the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the World Council of Churches, and the International Rescue Committee.55 Individuals also took the initiative to collect donations on the street to help the refugees (fig. 16).

In Vienna, many voluntary agencies had quickly organized to provide relief for the refugees, such as the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the Lutheran World Federation, the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), the World Council of Churches, and the International Rescue Committee.55 Individuals also took the initiative to collect donations on the street to help the refugees (fig. 16). At the Canadian Embassy, the Zends obtained visas to enter Canada (fig. 17). Before moving on, they stayed in Vienna for a few days, spending time with friends whom they knew they would not see for a long time, such as Skutai Ibolya, with whom Zend had worked at the children’s magazine Pajtás (Pal) in Budapest, and István Radó, who had organized the Zends’ escape and who was headed for the United States with his family (fig. 18). Zend would remain friends with Radó for the rest of his life, often flying from Toronto to visit him at his home in Los Angeles.

At the Canadian Embassy, the Zends obtained visas to enter Canada (fig. 17). Before moving on, they stayed in Vienna for a few days, spending time with friends whom they knew they would not see for a long time, such as Skutai Ibolya, with whom Zend had worked at the children’s magazine Pajtás (Pal) in Budapest, and István Radó, who had organized the Zends’ escape and who was headed for the United States with his family (fig. 18). Zend would remain friends with Radó for the rest of his life, often flying from Toronto to visit him at his home in Los Angeles.

Taking the next step on their journey to a new country and home, the Zends gathered their few belongings in a cardboard box, took a taxi to the Vienna train station (fig. 19), and made their way to Liverpool. There, they boarded a Cunard Line ship, travelling towards a freer but uncertain future in Canada.

Part 4. Canada: “Freedom, Everybody’s Homeland”

Robert Zend and his wife, Ibi, and eight-month-old baby, Aniko, escaped Hungary in mid-November 1956 when the Soviets crushed the Hungarian Revolution. After receiving Canadian visas in Vienna, they traveled by train to Liverpool, where they boarded an ocean liner headed for Halifax (fig. 1). In Canada they could start a new life free from government repression and terror. They had fled along with a huge exodus of other Hungarians also eager to leave before the Hungarian borders were completely locked down. By 1957, about 200,000 Hungarians had escaped, among which 37,000 immigrated to Canada as political refugees.1

The official Canadian response to the humanitarian emergency was slow at first, and there was even a decision in the early days of the refugee intake to admit into Canada only those who could pay for their own transportation. Public pressure from Canadians to respond to the crisis with generosity gathered impetus and had its intended effect on immigration officials. By the end of November, Canadian Minister for Citizenship and Immigration J. W. Pickersgill was persuaded to ease restrictions. He traveled to Vienna to announce the cutting of bureaucratic red tape and to offer free transportation to the refugees. Even so, old prejudices resurfaced when the director of immigration issued a caution that “those of the Hebrew race . . . in possession of a considerable amount of funds” might attempt to take advantage of the Canadian resettlement program. In spite of the initially conservative official response, the bureaucratic wheels gained momentum, and by mid-December about one hundred Hungarian refugees were arriving in Toronto every day.2 The Zends, who had been living at subsistence level in Budapest and in fleeing lost whatever meagre possessions they owned, benefited from the new, more lenient and generous refugee policies. On December 11 in Liverpool, along with 106 other Hungarian refugees and hundreds of regular passengers,3 they boarded the newly-built luxury liner Carinthia of the legendary Cunard Lines, courtesy of the Canadian government (fig. 2). Their journey to Halifax took twice the normal time due to stormy weather and rough seas, causing Ibi to suffer from seasickness. But the amenities of the Carinthia must have helped somewhat to ease the discomforts of the ship’s heave and sway (fig. 3).

The Zends, who had been living at subsistence level in Budapest and in fleeing lost whatever meagre possessions they owned, benefited from the new, more lenient and generous refugee policies. On December 11 in Liverpool, along with 106 other Hungarian refugees and hundreds of regular passengers,3 they boarded the newly-built luxury liner Carinthia of the legendary Cunard Lines, courtesy of the Canadian government (fig. 2). Their journey to Halifax took twice the normal time due to stormy weather and rough seas, causing Ibi to suffer from seasickness. But the amenities of the Carinthia must have helped somewhat to ease the discomforts of the ship’s heave and sway (fig. 3).

The Zends also befriended some of their fellow Hungarian passengers seeking asylum in Canada and the United States, documented by some poignant photographs on the ship by Zend (fig. 4).

Finally they arrived in Halifax on December 22. On their landing cards (fig. 5), Zend indicates his profession as reporter-journalist, and Ibi as librarian. Their religion is noted as Presbyterian. Considering the Nazi terror that Hungarians had experienced, it’s not difficult to understand the concealing of Ibi’s Jewish background, also keeping in mind that antisemitism was not limited to its long history in Europe but was also present and indeed institutionalized in Canada during the 1950s, as we have seen from the prejudice of the Canadian director of immigration. In addition, Jewish quotas and stricter admission standards were in place for universities such as McGill and the University of Toronto.

Finally they arrived in Halifax on December 22. On their landing cards (fig. 5), Zend indicates his profession as reporter-journalist, and Ibi as librarian. Their religion is noted as Presbyterian. Considering the Nazi terror that Hungarians had experienced, it’s not difficult to understand the concealing of Ibi’s Jewish background, also keeping in mind that antisemitism was not limited to its long history in Europe but was also present and indeed institutionalized in Canada during the 1950s, as we have seen from the prejudice of the Canadian director of immigration. In addition, Jewish quotas and stricter admission standards were in place for universities such as McGill and the University of Toronto. In Halifax, they boarded a train for Toronto. From the photographs Zend took from the train, his fascination with the vast stretches of snow, punctuated by a cluster of houses every few hours, is apparent (fig. 6). He and Ibi joked wryly that the landscape might well be Siberian — except of course for the occasional church steeple rising above a village.4 It was not an idle observation but one with ominous overtones, since after 1945 the Soviets had transported up to half a million Hungarians — among them poet György Faludy and writer György Gábori, survivors of the Gulag — to forced labour camps. Many of those camps were in Siberia, where a high percentage of inmates perished.5

In Halifax, they boarded a train for Toronto. From the photographs Zend took from the train, his fascination with the vast stretches of snow, punctuated by a cluster of houses every few hours, is apparent (fig. 6). He and Ibi joked wryly that the landscape might well be Siberian — except of course for the occasional church steeple rising above a village.4 It was not an idle observation but one with ominous overtones, since after 1945 the Soviets had transported up to half a million Hungarians — among them poet György Faludy and writer György Gábori, survivors of the Gulag — to forced labour camps. Many of those camps were in Siberia, where a high percentage of inmates perished.5 The Toronto population mobilized to provide housing and jobs for the new refugees to help them get started. From January to March 1957, a couple in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke gave the Zends a place to live in exchange for Ibi’s labour as a live-in domestic (fig. 7). Meanwhile, Robert put his experience in the Hungarian film industry to use when he found work at Chatwynd Studios editing film and doing odd jobs while he learned English. Soon thereafter, Ibi was able to find a job in her field as a librarian at the Toronto Public Library. Robert and Ibi were pleased to find that even on their low income during the first few years in Canada, they were able to afford things that were out of their reach in Hungary because either supplies were short or they couldn’t afford them. Aniko, who was born premature and who was sickly and undernourished the first eight months of her life , received the special nutrition she needed to flourish.6

The Toronto population mobilized to provide housing and jobs for the new refugees to help them get started. From January to March 1957, a couple in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke gave the Zends a place to live in exchange for Ibi’s labour as a live-in domestic (fig. 7). Meanwhile, Robert put his experience in the Hungarian film industry to use when he found work at Chatwynd Studios editing film and doing odd jobs while he learned English. Soon thereafter, Ibi was able to find a job in her field as a librarian at the Toronto Public Library. Robert and Ibi were pleased to find that even on their low income during the first few years in Canada, they were able to afford things that were out of their reach in Hungary because either supplies were short or they couldn’t afford them. Aniko, who was born premature and who was sickly and undernourished the first eight months of her life , received the special nutrition she needed to flourish.6 And for the first time in his life, Robert was able to afford a typewriter. In Hungary, it would have cost three months’ wages, but in Toronto he only needed to put a dollar down and pay affordable installments.7 He couldn’t know it then, but years later the typewriter was to become the instrument of an important body of his work in the categories of concrete poetry and typewriter art.

And for the first time in his life, Robert was able to afford a typewriter. In Hungary, it would have cost three months’ wages, but in Toronto he only needed to put a dollar down and pay affordable installments.7 He couldn’t know it then, but years later the typewriter was to become the instrument of an important body of his work in the categories of concrete poetry and typewriter art.

Zend describes the move to Canada as a “rebirth” and the new country like “a different planet” (fig. 8).8 And in important ways, life for the Zends had indeed improved. However, although remaining in Hungary would have placed Robert at great risk from the harsh reprisals of the Communist government, uprooting himself and his wife and baby from their native Hungary came with its own set of dilemmas and emotional trauma. He relates that his first five years in Toronto were “wretched,” and that for the next twenty he “felt like a man without a home” and a “misfit.”9

Zend’s unforeseen and precipitate departure from Hungary meant relinquishing his material possessions as well as his beloved Budapest and his friends and mentors. As he later quipped, “I lost everything except my accent.”10 As well, he had left behind all of his writing and personal mementos, which he had entrusted to a friend who stayed in Hungary. He later found out that his papers had disappeared or been destroyed when their apartment was ransacked in the chaos following the failed Uprising. He had been on the brink of publishing a one-hundred-page poetry book with a dissident publisher. The crushing loss haunted him for the rest of his life. 11

He revisited his family’s escape in “Chapter Fifty-Six,” a thinly-veiled autobiographical short story that posits an alternative history, a recounting of the rebellion of Maletrian citizens and its quashing by Romarmian forces. The protagonist tries unsuccessfully to escape with his family, but they are stopped at the border and are compelled to return to their home. He discovers the cause of the robotically compliant behavior of the citizenry following the brutal invasion: the Romarmian military had installed a “dream broadcasting centre” in the Ministry of Cultural Affairs to brainwash the people. Unlike actual history, the outcome is positive as he blows up the Ministry and the people are able to think freely again.12

More often, however, the sorrow of exile from his homeland echoes throughout his writings during these early years in Canada. Loneliness and alienation are common themes, as he tells of feeling like a person with no country, acutely aware of his “solitude among a thousand people”:

This is the real solitude bearing the whole world within

Consuming colours and sounds and growing big with them and

choking with them

Strangers have locked all the doors around me

Ghosts are stalking the desolate corridors

the walls are tense and about to explode13

In addition to writing of feelings of alienation, Zend, profoundly affected by the sudden and unexpected immigration, wrote “about the change, the culture shock, the homesickness, about the schizoid emotions of an exile between two worlds.”14Much later, during a trip to Budapest in the 1980s, he drew a sketch, “Split Zend,” showing his divided self — perhaps in reaction to experiencing once more the shift within himself that started in 1956 (fig. 9). He succinctly expresses the ambivalence of being mentally split between Budapest and Toronto in his poem “In Transit”:

In addition to writing of feelings of alienation, Zend, profoundly affected by the sudden and unexpected immigration, wrote “about the change, the culture shock, the homesickness, about the schizoid emotions of an exile between two worlds.”14Much later, during a trip to Budapest in the 1980s, he drew a sketch, “Split Zend,” showing his divided self — perhaps in reaction to experiencing once more the shift within himself that started in 1956 (fig. 9). He succinctly expresses the ambivalence of being mentally split between Budapest and Toronto in his poem “In Transit”:

Budapest is my homeland

Toronto is my homeIn Toronto I am nostalgic for Budapest

In Budapest I am nostalgic for TorontoEverywhere else I am nostalgic for my nostalgia15

As late as 1981, in a prose poem entitled “Fused Personality,” he writes that “[t]he deepest regions of my soul don’t seem to accept that I split myself and my life in two, in 1956.” He recounts a dream of living in a city at once Toronto and Budapest, sitting in a café having a stimulating conversation with Canadians Margaret Atwood, Glenn Gould, and Northrop Frye, as well as Hungarians Frigyes Karinthy, Béla Bartók, and Zoltán Kodály. He then leaves to find a table to write alone:

I write a poem for the excellent literary magazine called Search for Identity. I write down the title in Hungarian, but I realize that my English readership won’t understand it, so I cross it out and write it down again in English, but now I think about my oldest childhood friends who won’t be able to read it. My right hand holding the pen freezes in mid-air while I ponder the problem . . .16

At his idealized café table in a blended city, Zend assembles a dream coterie of Hungarian and Canadian cultural icons, who reach across anachronisms and language barriers to engage in brilliant conversation. But paralysis sets in when he must choose to write in one language or the other. The symbolism seems quite clear, yet it poignantly brings home the depth of the impression made by the culture shock of 1956 and the ongoing dilemma of identity, not only for Zend but for many thousands of refugees.

The title of the magazine, Search for Identity, is perhaps also a reference to the Canadian quest for cultural identity and cohesiveness. In Zend’s humorous piece entitled “An Interview with a Newborn Baby,” an interpreter translates the babytalk response to the question, “How do you like Canada?”:

Canada is a country that is engaged in an unrelinquished search for its “Identity,” and — due to this fact — it is quite impossible to determine whether one likes it or not. How can one like or dislike a territorial unit which doesn’t even know whether it exists or not and if not, why, and if yes, why not?

Zend riffs on the pop culture question pointing to the ongoing identity complex of a country perennially striving to distinguish its culture, especially from that of the United States. Zend, who explores in his writing and concrete poetry his own troubled and ambivalent feelings about cultural identity, settled in a country having an identity dilemma of its own. He felt the irony of that situation, which in “Interview” he resolves by pointing out (via the babbling baby) a basic fact of human universality:

Canada as such is not very different from any other country in the world. After all, they all have newborn babies who are starved and need instant breast-feeding.17

And in a short poem ending his speech on the evils of labeling people, he comments, tongue firmly in cheek:

The play on “identity” and “identical” creates a paradox because of the ambiguity of the latter. Again, Zend’s solution is to embrace the commonality of basic human needs. As he wryly notes in a journal, pointing out the inherent contradiction in the quest for Canadian identity:

Why search for Canadian identity? We found it. Anybody who searches for Canadian identity is a Canadian. Consequently: He who has found his Canadian identity is not a true Canadian.19

Some of Zend’s concrete poetry such as “BUDAPESTORONTO” (fig. 10) graphically epitomizes his complex and conflicted feelings about the two cities: Budapest, cosmopolitan and cultured yet also a place where intellectuals were censored and oppressed, and sometimes in danger for their lives; versus relatively “prosaic” Toronto, as Zend puts it in “Return Tickets” — “huge, clean, and functional.”20

Some of Zend’s concrete poetry such as “BUDAPESTORONTO” (fig. 10) graphically epitomizes his complex and conflicted feelings about the two cities: Budapest, cosmopolitan and cultured yet also a place where intellectuals were censored and oppressed, and sometimes in danger for their lives; versus relatively “prosaic” Toronto, as Zend puts it in “Return Tickets” — “huge, clean, and functional.”20

He also faced an uncertain future as a writer in a country whose language he had not previously studied. Arriving in Canada with his wife and baby, he quips that the first English word he learned was “diaper.”21 Magyar does not have Indo-European roots; neither does it share with English the etymological origins and grammatical structures (he describes Magyar as “extremely condensed” compared to English)22 that make it relatively easy to gain fluency within the closely-related Romance languages, for example.

In a short fantastical prose piece entitled “The World’s Greatest Poet,” Zend writes of Granduloyf, a poet who moves from Uangia to Obobistan and has difficulty learning the new language, which underscores for him not only grammatical but also cultural differences. His inability to reconcile the cultural with the linguistic occasions the poem:

While his people had no words for human character, but only for changing moods, the Obobs could not recognize changes in individuals. They thought of themselves as impenetrable iron bricks. . . . Like migrating birds, guided by ancient instinct, circling aimlessly over the ocean waves searching for Atlantis, the sunken destination of their migration, his pen circled aimlessly over the white paper and could not descend.23

Here Zend uses an image of paralysis similar to that in the dreamed café poem. The pen, like a migrating bird searching for a lost civilization, is unable to land words on paper. The poet as well as his language are exiled. Zend creates an artificial alphabet in a concrete poem to represent his perception of the differences between the two languages (fig. 11).

The poet’s initial awkwardness with the new language appears in the angularity of its alphabet as opposed to the graceful curves of his mastered native tongue. Zend’s own language barriers on arriving in Canada show through the veneer of fiction as he expresses the poet’s frustration of not being able to “ask for a packet of cigarettes without making himself look ridiculous.”

In addition to the challenges of learning a new language, Zend felt himself to be linguistically and psychologically “in limbo because I wasn’t a Canadian citizen yet, but I was no longer a Hungarian either.” He felt torn between writing and publishing in English or in his native language. He couldn’t yet write in English for Canadian publications, but neither could he write for Hungarian journals or presses because, “having illegally left the country, [he] was considered an enemy.”24 And his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. At that time, there were no Hungarian ethnic literary publications in Canada. So for about a year in 1961, he published his own Hungarian literary monthly, The Toronto Mirror (fig. 12). However, his advertisers, “unable to think but in labels,” wanted to know whether his publication was for “leftists or rightists, for Catholics or Protestants, for Jews or Gendarmes, for junior or senior citizens.”25 Zend had felt himself to be a “misfit” in Hungary, and that had not changed in Canada. Canadian publishers also were in a quandary about how to categorize him, wanting to know whether he was famous in Hungary.

And his decision of whether to publish in Canada or Hungary was fraught with catch-22’s. At that time, there were no Hungarian ethnic literary publications in Canada. So for about a year in 1961, he published his own Hungarian literary monthly, The Toronto Mirror (fig. 12). However, his advertisers, “unable to think but in labels,” wanted to know whether his publication was for “leftists or rightists, for Catholics or Protestants, for Jews or Gendarmes, for junior or senior citizens.”25 Zend had felt himself to be a “misfit” in Hungary, and that had not changed in Canada. Canadian publishers also were in a quandary about how to categorize him, wanting to know whether he was famous in Hungary.

In the 1960s, Hungarian exiles were allowed to return to Hungary as tourists (once the government, needing “hard currency . . . changed our labels from ‘Counter-Revolutionary Hooligans’ to ‘Our Beloved Fellow-Country-Men Living Abroad’”). Zend seized the opportunity to fly to Budapest and meet with Hungarian publishers, only to be asked whether he was famous in Canada. Once again, Zend was faced with a lack of sympathy due to nationalistic labels. They asked, “If you are a Hungarian poet, why do you live in Canada? If you are a Canadian poet, why do you want to publish in Hungary?” One Hungarian publisher suggested labeling him as a Canadian poet whose poems had been translated into Hungarian, telling him that he had “never published the original Hungarian poetry of Hungarian poets living in exile, in Hungarian, in Hungary! We just cannot start a new trend!” Zend’s assertion “that being a poet does not depend on the geographical location of the poet’s body, or on the political system under which the publisher functions, but on the linguistic and literary value of the poems” did not convince any Hungarian publisher.26

Realizing the need to publish in English in order to establish himself as a writer in Canada, he decided to learn the language to the point that he could write poetry independently in it. His linguistic talents and his mastery of Italian and study of Latin and German no doubt helped him as he gained fluency in the new language. By 1964 he was writing poems in both Hungarian and English. He also worked closely with John Robert Colombo, a literary scholar and poet in Toronto, on translating the poems originally written in Hungarian and published in his first two poetry collections: From Zero to One (1973) and Beyond Labels (1982).

Determined to write his poems effectively in English, Zend took pains to transfer his musical feeling for his native language into his adopted one. Revisions of poems written in English during the 1960s shows him trying multiple versions, taking care that the language be musical and that the rhythm mesh with the content. In “No,” for example, he writes of honing the rhythm to achieve a percussive beat to reflect the knocking on a door of an unborn being, and towards the end of the poem creating a rhythm that “widens and calms down to annihilate” as the being becomes “lost / in the snowy fields of non-existence.”27 It’s not surprising that Glenn Gould calls Zend “unquestionably Canada’s most musical poet,” high praise from one of Canada’s greatest musicians.28

Finding employment in Toronto proved to be a huge setback for Zend. He worked at a series of menial jobs in order to support his family. In From Zero to One, he expresses frustration at having to restart his career with such labour “at the dreadful place where the supervisors / imagine themselves prison guards,”

where we have to put on cards

our comings and goings

and every moment of lateness or early leaving

has to be accounted for

but if during the eight hours we redeem the world

or just twiddle our thumbs

no one cares —29

In addition to such frustrations, Zend relates that his experience with labels did not end upon escaping Communist Hungary and immigrating to Canada: “the free world didn’t deliver me from evil labels.”30 In a story published in the Toronto Star in 1992, Ibi relates an encounter with antisemitism soon after the move to Canada, when they were living with the couple in Etobicoke:

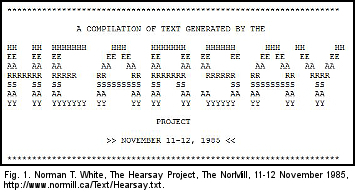

Until one night the couple noticed the Auschwitz identification mark on [Ibi’s] arm. “You mean you are Jews!” said the husband. Next day they were sent packing.31