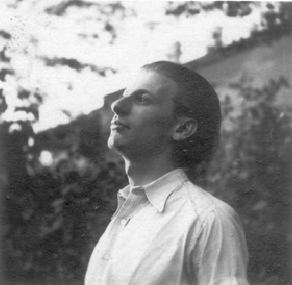

November 10 marked the sixty-fifth anniversary of the murder of Miklós Radnóti, a Jewish Hungarian poet killed by Hungarian Nazi collaborators during a three-month death march and buried in a mass grave. A year and a half later, when his wife, Fanny, located and exhumed his body, a notebook of his poems was found in his coat pocket. Radnóti had continued to write poetry during his internment in various work camps, his slave labour in a copper mine, and his forced march across his native Hungary, bearing witness to the horrors to which he ultimately succumbed.

As a tribute to him, I’m reproducing six of his poems below. The first is an eclogue, which is an ancient pastoral poem in the form of a dialogue between shepherds. Radnóti’s eclogue imagines a dialogue between an unlikely pair—a fighter pilot and a poet—that reveals his deep concern with human empathy.

The next five poems, “Forced March” and four short “Postcards,” are the last that Radnóti composed before his execution. Soon after writing the fourth “Postcard,” Radnóti was badly beaten by a soldier annoyed by his scribbling into a notebook. Soon thereafter, the weakened Radnóti and twenty-one of his fellow Hungarian Jews were shot to death and buried.

These last poems, written under the pressure of the most degrading and desperate circumstances imaginable, unfurl visions of delicate pastoral beauty next to images of extreme degradation and wild, filthy despair. They give voice to the last vestiges of hope as Radnóti fantasizes being home once more with his beloved Fanny, as well as to the grim premonition of his own fate. This impossibly stark contrast blossoms into paradox: Radnóti’s poetry embraces humanity and inhumanity with an urgent desire to bear witness to both. Yet even at the moment when he is most certain of his imminent death, he never abandons the condensed and intricate language of his poetry. And pushed to the limits of human endurance and sanity, he never loses his capacity for empathy.

The Second Eclogue

Pilot:

We went pretty far last night. I was so angry I laughed.

Fighters buzzed me like a swarm of bees.

They had good protection. Friend, you should have seen how they fired.

Finally another one of our squadrons appeared on the horizon.

I barely missed getting shot down and having pieces of me swept up down below.

But I’m back you see. And tomorrow I’ll tremble with fear again

and a frightened Europe will hid in its cellars from me—

Oh, forget it. I’ve had enough. Did you write again today?

Poet:

Yes, I wrote. What else can I do? Poets write, cats wail, dogs howl

and small fish coyly scatter their eggs. I write about everything.

I even write for you, so you’ll know I’m alive.

I write when the light of the bloodshot moon stumbles

among the exploding, collapsing rows of houses,

when terrified parks are torn up, when breathing stops,

when even the sky vomits, and the planes keep coming.

They disappear and then swoop down again, like the roar of madness!

I write. What else can I do? And a poem is very dangerous,

if you only know how sensitive, how unpredictable even one line is!

You need bravery for all this, you see. Poets write, cats

wail, dogs howl, and small fish—

and so on— But what do you know? You listen to the plane

and your ear buzzes with the noise even when you can’t hear it.

Don’t deny it, the plane’s your friend. It’s part of you.

What are you thinking about when you fly over us?

Pilot:

You can laugh but I’m afraid up there. I close my eyes and think

about my girl, about lying in bed down here.

Or I only sing about her, between my teeth, quietly,

in the crazy uproar of the steaming soldiers’ club.

Up there, I want to come down. Down here, I want to fly again.

There’s no place on earth for me.

And I know the airplane means too much to me,

but up there the rhythm of our pain is the same—

You know what I mean! You’ll write about it. It won’t be a secret

any more that I, who only destroy now, lived like a man too,

homeless between the earth and the sky. O God, who will understand—

Will you write about me?

Poet:

If I’m alive. If there’s anyone left.

Apri. 27, 1941

Forced March

You’re crazy. You fall down, stand up and walk again,

your ankles and your knees move pain that wanders around,

but you start again as if you had wings.

The ditch calls you, but it’s no use you’re afraid to stay,

and if someone asks why, maybe you turn around and say

that a woman and a sane death a better death wait for you.

But you’re crazy. For a long time now

only the burned wind spins above the houses at home,

Walls lie on their backs, plum trees are broken

and the angry night is thick with fear.

Oh, if I could believe that everything valuable

is not only inside me now that there’s still home to go back to.

If only there were! And just as before bees drone peacefully

on the cool veranda, plum preserves turn cold

and over sleepy gardens quietly, the end of summer bathes in the sun.

Among the leaves the fruit swing naked

and in front of the rust-brown hedge blond Fanny waits for me,

the morning writes slow shadows—

All this could happen! The moon is so round today!

Don’t walk past me, friend. Yell, and I’ll stand up again!

September 15, 1944

Postcard 1

From Bulgaria the huge wild pulse of artillery.

It beats on the mountain ridge, then hesitates and falls.

Men, animals, wagons and thoughts. They are swelling.

The road whinnies and rears up. The sky gallops.

You are permanent within me in this chaos.

Somewhere deep in my mind you shine forever, without

moving, silent, like the angel awed by death,

or like the insect burying itself

in the rotted heart of a tree.

In the mountains

Postcard 2

Nine miles from here

the haystacks and houses burn,

and on the edges of the meadow

there are quiet frightened peasants, smoking.

the little shepherd girl seems

to step into the lake, the water ripples.

The ruffled sheepfold

bends to the clouds and drinks.

Cservenka

October 6, 1944

Postcard 3

Bloody drool hangs on the mouths of the oxen.

The men all piss red.

The company stands around in stinking wild knots.

Death blows overhead, disgusting.

Molhács

October 24, 1944

Postcard 4

I fell next to him. His body rolled over.

It was tight as a string before it snaps.

Shot in the back of the head—“This is how

you’ll end. Just lie quietly,” I said to myself.

Patience flowers into death now.

“Der springt noch auf,” I heard above me.

Dark filthy blood was drying on my ear.

Szentkirályszabadja

October 31, 1944

All of the poems above are from Clouded Sky, a collection of Radnóti’s work translated by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S. J. Marks ( New York: Harper & Row, 1972).

Camille Martin

http://www.camillemartin.ca

Thanks for printing these. They’re beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Roundup: Poetry Close Readings and Appreciations « Rogue Embryo

FINE BRIEF INTRO TO THIS SUPERB POET. It helped me write my blog at http://tomdevelyn.info/

LikeLiked by 1 person

MIKLOS IS A GREAT POET, I TRANSLATE HIS POEM IN PUNJABI, THIS TRANSLATION IS GOOD. I GET SOME HELP FROM IT, THANKS

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome! I also admire these translations in free verse. Another possibility is to try to imitate the formal patterns that he used in Hungarian – see here: http://kimtrainorblog.wordpress.com/tag/miklos-radnoti/ Best wishes in your translation.

LikeLike